Of all the poets of the Hyakunin Isshu anthology, arguably the most famous, especially overseas is Lady Murasaki (poem 57), who in Japanese is called Murasaki Shikibu (紫式部). She is the author of the Tales of Genji, which epitomized life in Japanese antiquity, and is among the first novels in history. But another work by Lady Murasaki that’s notable here is her eponymous diary, of which an illustrated version appeared centuries later. In English this is simply known as the Diary of Lady Murasaki (murasaki shikibu no nikki, 紫式部の日記).

The diary covers the period from years 1008 to 1010, and provides a first hand account of her life serving the powerful regent, Fujiwara no Michinaga. Michinaga is not featured in the Hyakunin Isshu, but his power as regent was great enough to ruin the lives of a few poets in the anthology:

Michinaga was locked in a power-struggle between his branch of the Fujiwara Clan, and another branch, led by Morechika. Both had daughters married to Emperor Ichijō, and both were fighting to be the regent (kanpaku, 関白) of Ichijō’s heir. In the end, Michinaga’s daughter, Empress Shōshi, gave birth to the future Emperor Go-Ichijō (Ichijō the Latter). With it, Michinaga became the most powerful man in Japan.

At the beginning of the diary, Lady Murasaki describes the events leading up to Empress Shōshi giving birth, and the elaborate ceremonies to protect her and the unborn child from evil spirits. Although it was technically a private ceremony, Michinaga hired an army of priests and shamans to both bless the child, and also to ward off evil spirits. Lady Murasaki, as a member of the household, describes sitting in the crowded audience chamber for hours, listening to the fevered chanting and elaborate rituals.

Then the diary skips ahead to the first weeks of the child’s birth, and further ceremonies. Michinaga spares no expense to protect his grandson (whom he will be the regent of, and thus the true power behind the throne) from diseases, evil spirits and so on. In elaborate rituals, members of the household are selected to read the Confucian Classics to the baby to ensure he will be an august ruler. More priests are called into ward off evil, and so on.

But what about Lady Murasaki?

Lady Murasaki herself comes from a lesser branch of the Fujiwara clan, and since her husband already died some time ago, she describes herself as “washed up”. She held no official appointment in the Imperial Court. And yet, through Michinaga, she becomes a trusted confidant and tutor of the Empress. Michinaga knew talent when he saw it, and wasn’t shy about packing his household with as much as he could get away with.

Lady Murasaki was but one of several famous ladies-in-waiting recruited by Fujiwara no Michinaga to increase the status of his daughter, Empress Shōshi, vis-a-vis the Emperor’s first wife, Teishi (Morechika’s daughter).

Lady Murasaki’s diary implies that life as a lady-in-waiting is a lot of “hurry up, then wait”: periods of great activity and ceremony, followed by long periods of boredom. The period after the child’s birth eventually winds down and leads to a lot of free time, where Lady Murasaki reflects on many things, as well as disparaging some of the other ladies-in-waiting. Here are some examples of her contemporaries who also happen to appear in the Hyakunin Isshu:

- Lady Izumi (poem 56) – “She does have a rather unsavory side to her character but has a talent for tossing off letters with ease and seems to make the most banal statement sound special.“

- Akazome Emon (poem 59) – “She may not be a genius but she has great poise and does not feel she has to compose a poem on eveyrthing she sees, merely because she is a poet.“

- Sei Shonagon (poem 62), part of the rival clique under Empress Teishi – “…was dreadfully conceited. She though herself so clever and littered her writings with Chinese characters; but if you examined them closely, they left a great deal to be desired.“

She also grapples with persistent depression. Her sullen, introverted nature often wins her few friends among other ladies of the Court:

And when I play my koto rather badly to myself in the cool breeze of the evening, I worry lest someone might hear me and recognize how I am just ‘adding to the sadness of it all’; how vain and sad of me. So now both of my instruments, the one with thirteen strings and the one with six, stand in a miserable, sooty little closet still ready-strung.

The diary then jumps forward into a letter written at a later date. The intended recipient is unknown, but is thought to be her daughter Daini no Sanmi (poem 58). Here the diary includes a great deal more self-reflection, and further analysis of the other ladies in waiting, including her grievances with another clique of ladies centered around the high priestess of the Kamo Shrine, Princess Senshi (daughter of Emperor Murakami).

Finally, the diary jumps around a few more times in narrative, and then abruptly stops. Richard Bowring points to theories that other fragments of the diary once existed, possibly some in the Eiga Monagatari, or some possibly in possession by Fujiwara no Teika (poem 97, and compiler of the Hyakunin Isshu), but these are all speculation.

The Diary is pretty short; you can read it cover to cover in a couple of hours. And yet it’s a fascinating blend of historical perspective, and very relatable personal reflection. Loneliness and depression affect people of today as much as it did people of her time, and yet she has to carry on through stodgy court ceremony, pressures of the insular life in the aristocracy, and constant back-biting amongst the ladies-in-waiting.

In one lengthy anecdote, she describes a prank that the other ladies-in-waiting decide to pull on one Lady Sakyō, who apparently had retired from service, then returned to serve another nobleman. The prank was to send a luxurious “gift”, but with a lot of symbolism regarding youth, implying ironically that Lady Sakyō was an old has-been.

And then there’s the sexual harassment….

The diary lists several incidents where drunken nobles harass attractive servants during dinner, servants who are unable to really do anything about it since they owe their entire livelihood to those nobles. Alternatively, the noblemen, bored themselves, play mean pranks on the ladies, steal their robes, or pull their skirts. Because of the power imbalance (also frequently alluded to in the Gossamer Years), it was just an accepted part of life, and the ladies often had to regularly dodge that minefield.

Middle Counselor Elect Taka’ie, who was leaning against a corner pillar, started pulling at Lady Hyōbu’s robes and singing dreadful songs. His Excellency [Michinaga] said nothing….Realizing that it was bound to [be, sic] a terribly drunken affair this evening, Lady Saishō and I decided to retire once the formal part was over.

trans. by Richard Bowring

Michinaga himself frequently bursts in on Lady Murasaki, sometimes drunk, demanding a quick poem or a verse for particular occasions. Although Michinaga never makes advances on Lady Murasaki, his overbearing demeanor exhausts her, yet she also admires his quick wit and ambition. I can imagine Michinaga in moderns times being a flashy, talented CEO with a dubious reputation :

I felt depressed and went to my room for a while to rest. I had intended to go over later if I felt better, but then Kohyōe and Kohyōbu came in and sat themselves down by the hibachi. ‘It’s so crowded over there, you can hardly see a thing!’ they complained. His Excellency [Michinaga] appeared.

‘What do you think you’re all doing, sitting around like this?’ he said. ‘Come along with me!’

I did not really feel up to it but went at his insistence.

trans. by Richard Bowring

Another frustration that Lady Murasaki describes is the rigid social hierarchy within the aristocracy. Lady Murasaki was from a middle-ranked family, and while not a menial servant herself, she was frequently reminded of her place. This included things like being unable to wear the “forbidden colors“, where she sat during court ceremonies, and whom she was allowed to address directly. Lady Murasaki sums it like so:

The water-music that greeted the Emperor was enchanting. As the procession approach, the bearers — despite being of low rank — hosted the palanquin right up the steps and then had to kneel face down beneath it in considerable distress. ‘Are we really that different?’ I thought to myself as I watched. ‘Even those of us who mix with nobility are bound by rank. How very difficult!’

trans. by Richard Bowring

What she often describes, when reading between the lines, is that for all its pomp, culture and beauty, life in the Heian Period aristocracy was a kind golden sham:2

I returned to the Palace on the twenty-ninth of the twelfth month [after a month absence]. Now I come to think of it, it was on this very night that I first entered service at court. When I remember what a daze I was in then I find my present somewhat blasé attitude quite uncomfortable.

trans. by Richard Bowring

One other thing to note is that her diary alludes to the Tales of Genji frequently. By the time she was recruited by Michinaga, a few drafts of the work had already been in circulation, and this probably helped her reputation. Even the illustrious Fujiwara no Kintō (poem 55) pays her a brief visit in the diary calling her “Murasaki” (e.g. purple) as an allusion to one of her characters in the novel. Richard Bowring implies that this moment might be how Lady Murasaki got her sobriquet.3 We saw this with Nijōin no Sanuki (poem 92) in later generations as well. Sadly, it seems that these copies of the Tales of Genji were sometimes borrowed and never returned, or copied by other people, and since each copy took so long to compose, Richard Bowring implies that it is a miracle that the work survived at all.

In any case, the Diary of Lady Murasaki is probably one of the best descriptions of life in the Imperial Court and its (often oppressive) aristocracy. It was a world of beauty and also of frustration and bitterness.

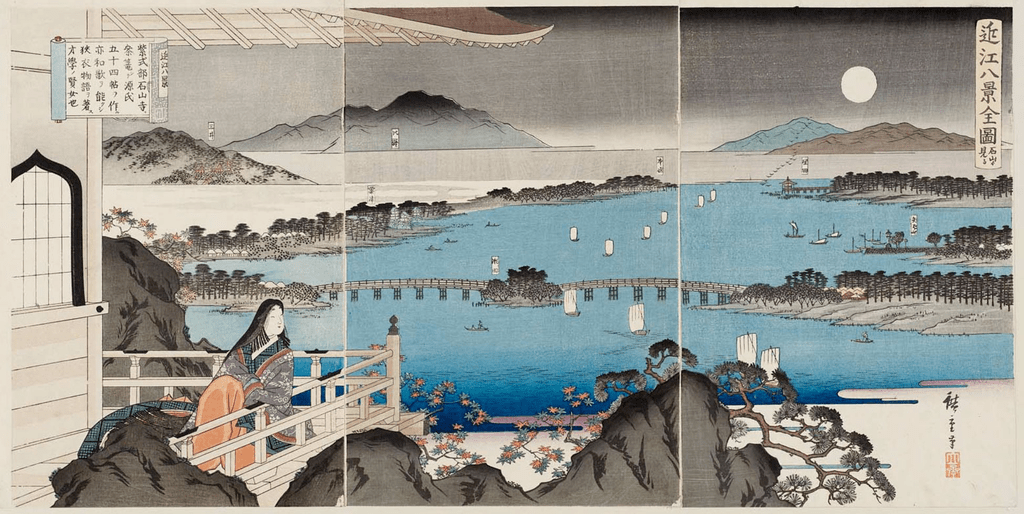

P.S. Photo is a famous woodblock print by Utagawa Hiroshige (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons), depicting a legend about Murasaki Shikibu at Ishiyama Temple. These are the 3 panels of the nishiki-e: “Eight Views of Omi Province as Seen from Ishiyama” (Ômi hakkei zenzu, Ishiyama yori miru). Notice her purple (murasaki) robes.

1 Sei Shonagon was a lady in waiting for Empress Teishi, who was a daughter of Michinaga’s rival. When Michinaga’s rival is driven out by a scandal, Teishi is relegated to the background, and Sei Shonagon retires in obscurity.

2 Valkyrie in the movie Thor: Ragnarok had said much the same thing about Asgard, too.

3 Her true name is not known, but is thought to be Fujiwara no Kaoriko (藤原香子).