Recently I learned about the concept of go-shoku Hyakunin Isshu (五色百人一首), or five color Hyakunin Isshu.

During my recent trips to Japan, while shopping for Karuta sets, I did see some advertised as “five color sets” but didn’t understand the significance, and there is no information in English.

According to this helpful website, it’s a kind of teaching aid for grade school kids to learn Karuta by diving the cards into 5 sets of 20, color-coded: Blue, Pink, Yellow, Green and Orange. The website above has a comprehensive chart for each color, and which poems belong to each.

The cards are grouped this way to ease the memorization of the kimari-ji for playing karuta by organizing easier versus more difficult cards into different groups. The website above suggests the following game to help (my rough translation below):

- This is a 1v1 game

- Of the five color groups, select one at random (or however you want to decide).

- Shuffle the 20 cards and then divide into two piles. Using rock-paper-scissors to decide, the winner can pick their preferred pile.

- Each player will lay out their cards in two rows of 5 cards each. Lay your cards out so that you can read them.

- The tops of your cards on the top row will touch the top of your opponent’s cards on their top row. Your cards do not have to be touching each other.

- You have one minute to memorize your cards.

- The reader will reader the upper verses of the poem, then the lower verses, one time each.

- When you are going to take the card, yell hai!

- If both players touch the card at the same time, you can decide the winner using rock-paper-scissors.

- If one player’s hand is on top of another, the player who’s hand is at the bottom is the winner.

- When the reader is not reading cards, you are allowed to flip the cards over to see the upper verses. (Me: I guess the official five color cards print on both sides?)

- When 17 cards have been read, the match is over.

- Whoever took the most cards wins.

There is a helpful instructional video too (sorry, no English):

It also points out some penalties: touching the wrong card (even if you touch the correct one later) and such. Most of this is geared towards grade school kids, so adults would not likely make such mistakes.

Also, some groups seem easier than others. Based on reviews in the website above, yellow and blue seemed easiest, while orange and green were the hardest.

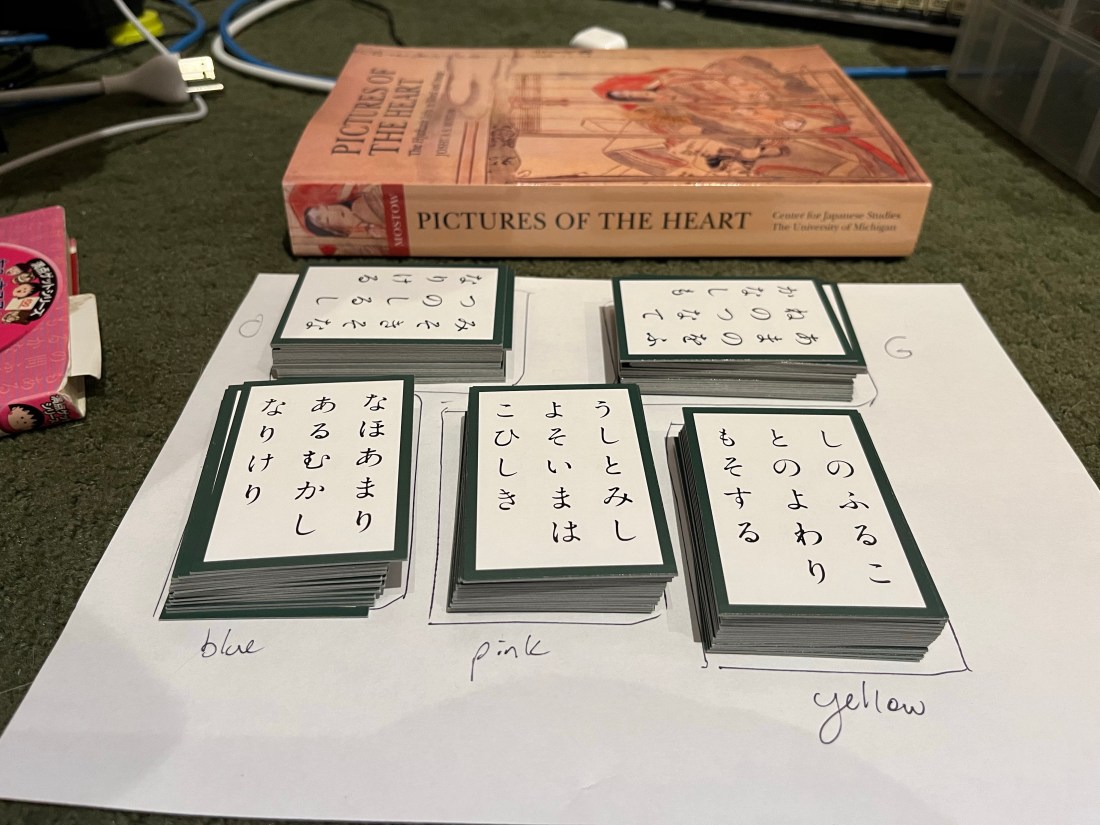

Since I don’t own an official five-color set (yet), I decided to make my own set by using one of my non-competitive sets, and dividing it up into the five color groups. You can see my efforts above in the featured photo. Also, please buy Dr Mostow’s book on the Hyakunin Isshu. This blog is graciously his debt. 😌

Even if you don’t play the five color Hyakunin Isshu game, you can still use an online reader app like Karuta Chant (iOS and Android). The app even has options for reading only the specified color group:

This established method of dividing up the cards into five colored groups is a very handy way to divide and conquer in your efforts to learn the karuta cards.

Try it out and let me know what you think in the comments!