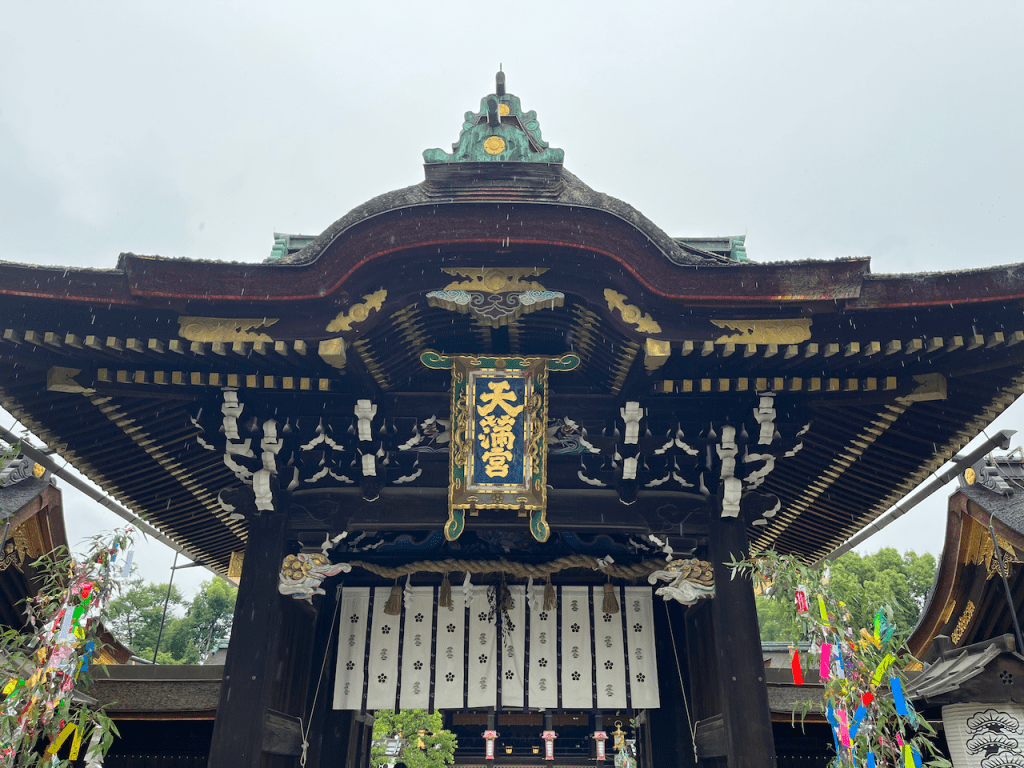

During our recent trip to Japan, we visited the city of Kyoto. I talked about this here, but I also wanted to share another site in Kyoto that relates to one of the poets of the Hyakunin Isshu : Kuramazaki Shrine. You can find their official website here, but there is no English and the site is a bit hard to navigate. The shrine itself has a very interesting layout:

The photo above is the main promenade leading to the inner sanctum (toward the back). Apparently, it’s tradition in Japanese culture to walk along the edge of the walkway, not right in the middle, so bear that in mind when visiting a shrine like this.

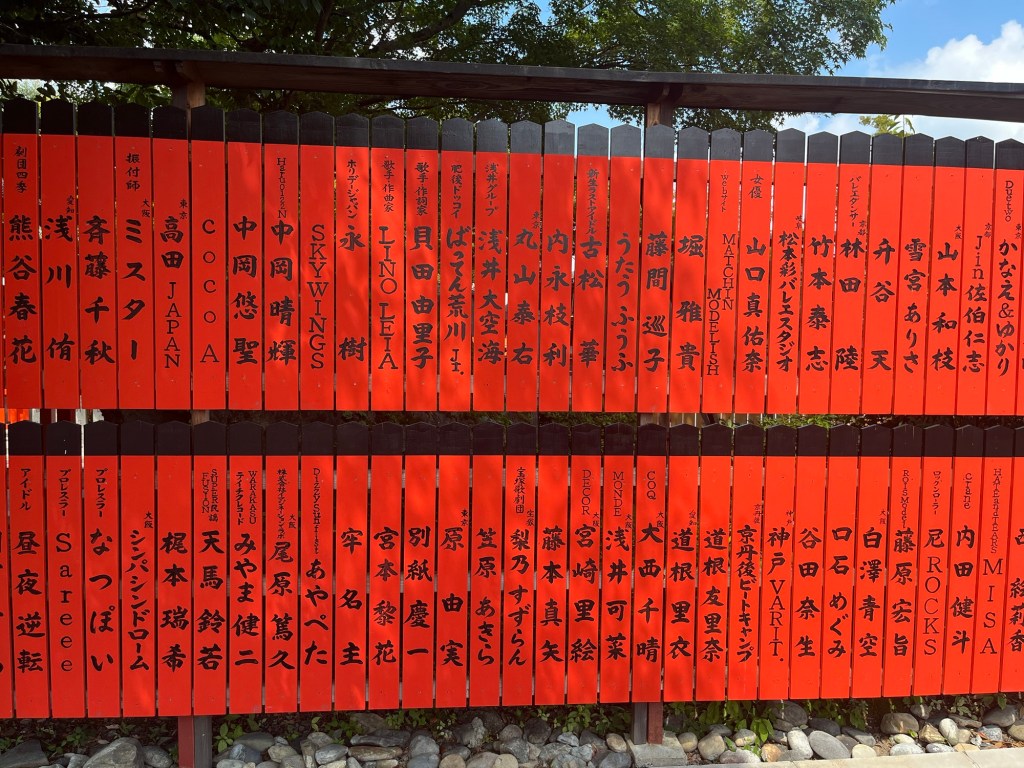

This Shinto shrine is notable for its many visits by celebrities who leave autographed red plaques.

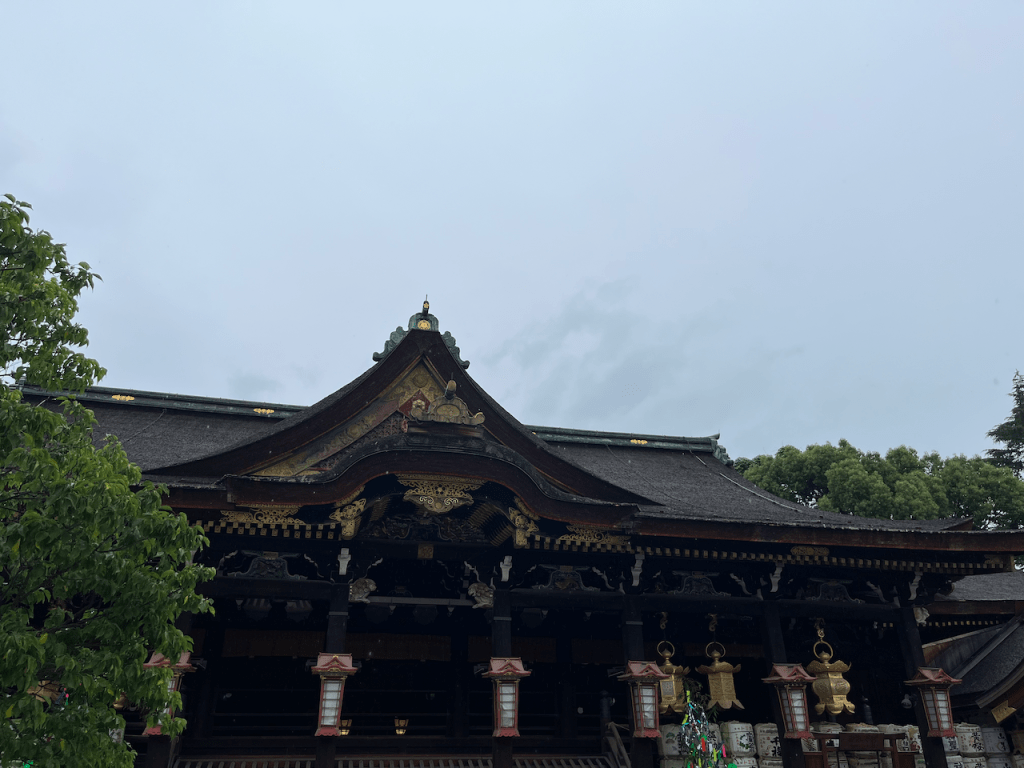

Shinto shrines often serve particular need in society: love, business success, health, etc. In the case of Kurumazaki Shrine, the focus is on show-business, acting, theater, etc.

Why does this matter?

It turns out that Sei Shonagon, author of the Pillow Book and poem 62 (よを) in the Hyakunin Isshu is enshrined here. Not only that, but you can purchase a special omamori charm with her image on it. I learned about this place on social media after seeing the actress First Summer Uika, who played Sei Shonagon in the historical drama, visit the shrine.

Because this site contains many sub-shrines and side passages, it took a bit of effort to find Sei Shonagon’s shrine. It is halfway down the promenade, on the left, and looks like so:

I paid my respects to this esteemed author, and the family and I continued to explore. I found First Summer Uika’s plaque near the inner sanctum:

Incidentally, my wife is a fan of the JPop group Snow Man, and you can see one of their markers just to the left. We both got something out of this trip. 😛

As I alluded to earlier, the shrine complex is deceptively long, with many nooks and hidden shrines and side paths. The site map gives some sense of this. For reference, the Sei Shonagon shrine is number 20 on the map, and you can see there are many other sites here too. I didn’t photograph every shrine here, and most are probably obscure to readers (and obscure to myself). The common theme was both fortune, and also show business. They were some pretty neat shrines though, such as this one showing various theater masks:

At last we came to the gift shop, and I got a Sei Shonagon charm (omamori):

Later, when I got back home and realized that the charm was intended for ladies,1 I was rather embarrassed, yet I didn’t want it to go to waste, so I gave it to my daughter whose preparing for college this year. It seemed fitting, and I am happy to report that she got a good score in her SAT exam the following month, so perhaps the charm worked?

Anyhow, Kurumazaki Shrine is not something tourists usually visit because it’s a little removed from the nearby touristy area of Arashiyama, and like many Shinto shrines, it’s very Japan-centric, but it’s a cool slice-of-life of Japanese popular culture, both past and present.

As for me, I was happy to pay my respects to such a wonderful poet and author directly, someone’s whose creativity and work indirectly helped make this blog what it is today.

P.S. Later that day, I stumbled upon the place where the Hyakunin Isshu was compiled, so I managed to visit two sites in one day. Not too shabby.

1 It’s clearly written on the signs, I just failed to pay attention. I was maybe a bit star-struck perhaps. 😅