This poem is a nice reminder that “traffic” and “commuting” are two things that haven’t really changed much in 1,000 years:

| Japanese | Romanization | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| これやこの | Kore ya kono | This it is! That |

| 行くも帰るも | Yuku mo kaeru mo | going, too, and coming too, |

| 別れては | Wakarete wa | continually separating, |

| 知るも知らぬも | Shiru mo shiranu mo | those known and those unknown, |

| 逢坂の関 | Ōsaka no seki | meet at the Barrier of Ōsaka |

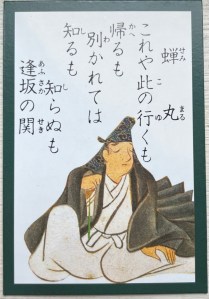

This poem was composed by one Semimaru (蝉丸, dates unknown) who is reputedly a blind man who built a hut near Osaka Barrier and was famous for playing the biwa, but the authenticity of this story is questionable, and as Mostow points out, it’s not even certain he existed at all. The story about his life has also changed throughout the generations, so in some cases he’s the servant of the son of an Emperor, and in others he’s the son of an Emperor, abandoned by his blindness.

According to one account in my new book, a high-ranking official named Minamoto no Hiromasa (源博雅) once heard a rumor of a talented blind man with a biwa lute who lived near the Osaka Barrier (see below). He wanted to hear this man’s music, and sought him out for three years until he finally found him on the evening of 15th day of the 8th month (old lunar calendar), and from this man, Hiromasa learned to play the songs that he had been squirreling away. Songs titled such as 流泉 (ryūsen, “flowing spring”) and 啄木 (takuboku, “woodpecker”).

The place in question, Osaka Barrier, is a popular subject of poetry from this era. Poems 62 and 25 also mention the same place because it was a popular meeting spot for people coming and going from the capitol (modern-day Kyoto) eastward. Note that this Osaka has no relation to the modern city of Osaka, which was called Naniwa during that era. In fact the name of Osaka Barrier is also a pun. The Chinese characters are 逢坂, which means “meeting hill”, but is also the place-name.

Anyway, these kinds of check-points, or sekisho (関所) existed in Japan across major roads going in and out of the capitol, but were also popular meeting places for friends and lovers too, as well as having inns nearby for weary travelers. The featured photo above is an example of “sekisho” checkpoint, photo by 663highland, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Osaka Barrier in particular was the first check-point leaving eastward from the capitol, so many people probably parted company here, or met old friends at this particular gate more than others. It’s fun to imagine what Osaka Barrier was like in those days. As Mostow points out, this poem probably was originally just a poem about Osaka Barrier, but by the medieval era, it took on an increasingly Buddhist tone in symbolizing the coming and going of all phenomena. Even modern Japanese books on the Hyakunin Isshu tend to reflect this sentiment. Pretty interesting metaphor I think.

One other interesting thing about this poem is its rhythm. If you read this one out loud, the rhythm is very easy to follow, and this is probably one of the easier poems to memorize if you’re looking for a place to start (poem 3 is another good choice in my opinion 😉).

Finally, one random note about Semimaru himself.

His artistic depiction in karuta cards, such as the yomifuda card above based on the famous Korin Karuta collection, leads to frequent confusion by people who play bozu mekuri: is he a monk or a nobleman? Even my new book mentions this conundrum among Japanese players. His lack of verified biographical information makes this question even more mysterious. The book jokes that the author’s house-rule is that if anyone pulls the Semimaru card, then everyone loses what their stack of cards. Feel free to make your own house-rule. 😊

Discover more from The Hyakunin Isshu

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.