Karuta is a game of memory and speed. You’re trying to take a specific poem card before your opponent does, and you can’t know which card it is until the reader starts reading the selected poem. So, players have to use clues called kimari-ji (決まり字), or “deciding letter (or character)” to determine which poem is being read as quickly as possible.

I had heard of the concept before, but in my quest to learn all 100 poems of the Hyakunin Isshu, I didn’t pay attention to kimari-ji, and thus during my first competition I struggled a lot. Learning an entire poem, and learning its kimari-ji are two separate skills. Over the long run, a person can do both, but if you want to play karuta you should invest in memorizing the kimari-ji for as many poems as you can.

What are kimari-ji though? These are the first letters (or characters, I’ll explain shortly) of poetic verse, that tell you which poem is being read. Since the cards on the floor, the torifuda cards, only contain the last two out of five verses of a poem, it’s not immediately obvious which is which. The reader has the full poem using the corresponding yomifuda card.

Anyhow, both the torifuda and yomifuda cards are written using Japanese hiragana script. Hiragana is not an alphabet. It’s a syllabary. Each letter/character is a self-contained syllable or ji (字) in Japanese. English uses an alphabet so it takes 2 letters to spell the syllable “go”, but in Japanese this would require a single character: ご.1

If you’d like to learn more about hiragana script, check out my other blog here and here. Learning hiragana is worthwhile not only because it will unlock the Japanese language, it will help you play karuta a lot more effectively. It takes effort to learn upfront, but the good news is that it’s a learn-once-use-often skill.

When first learning to play karuta, and memorizing the poems, you soon realize that cards often fall into common patterns just based on the first few hiragana syllables. Others stand out from the others and are thus easier to recognize during play.

Let’s look at an easy example, poem 77 (my wife’s favorite).

This poem begins with the first verse:

せをはやみ

se wo hayami

The “se” (せ) in “se wo hayami” is unique among the Hyakunin Isshu anthology in that there are no other poems that start with “se”. So, as soon as the reader says “se”, highlighted below in blue, a seasoned player knows the poem being read is number 77, and that its fourth verse starts with われても, shown in red below.

This is an example of a one-character (一字, ichiji) kimari-ji poem, also called a ichiji-kimari (一字決まり). Poems that can be recognized by the first two characters are niji-kimari (二字決まり), three-character poems are sanji-kimari (三字決まり), four are yojikimari (四字決まり), and so on.

At other extreme end are six-character kimari-ji poems, also commonly called ōyama-fuda (大山札, “big mountain cards”). Here’s an example below.

The yomifuda cards above are poem 64 (left) and poem 31 (right). Both start with the same 5-character verse, shown in green: asaboraké. It’s not until the sixth character (blue) that they differ. In this case, the sixth for poem 64 is “u” (う), and the sixth character for poem 31 is “ah” (あ). So, if you are listening to the poem, you have to wait all the way until the start of the sixth character to know which poem is being read. If you jump the gun and pick the wrong one, you get a foul (otetsuki, お手つき). Speaking from experience, I have done this. 🤦🏻♂️ It sucks.

In any case, vast majority of poems out there usually fall between these two extremes. The more you practice playing karuta, or memorizing them, the more you internalize them. This is important as kimari-ji work like a trigger: if you’ve memorize the “board state” (i.e. where everything is on the board), as soon as you hear the right syllables, BOOM, you take the card before your opponent does.

Shifting Kimari-ji and Late Game

As the game progresses, or depending on which cards are on the board, even six-kimariji card can become a one-kimariji card. How? This is called kimariji-henka (決まり字変化, “shifting kimariji”).

“Rachel” from the Seattle Karuta Club kindly provided the following chart for the blog:

This chart shows a breakdown of all 100 poems with their kimari-ji, sorted by the initial hiragana character on downward. This is important because if the cards start with naniwa-e (poem 88) and naniwa-ga (poem 19) are both on the board, you have to wait until the fourth syllable (e vs. ga) to determine which card to take. Because of their initial similarity, they are grouped together as tomofuda (友札, “friend cards”).

However, if one of the poems above has already been read, and another card with the kimari-ji nanishi (poem 25) has not, then you only need to determine which one to take based on naniwa vs. nanishi. You don’t have to wait until the fourth character. If there is only one card on the entire board that starts with “na” (usually very late in the game), you can trigger off just that.

As the cards on the board reduce in number, this comes up more and more. This is a slightly more advanced topic, but as you gain more experience, you’ll start to notice this too.

So…. How do you memorize them all?

There are many approaches to learning the kimari-ji, so you should find a method that works for you, and not be afraid to adjust that method if it’s not really working. Since my last karuta competition, I’ve shifted methods a few times. But there are some popular methods worth mentioning.

First of all, the 1-character kimari-ji can be remembered using this simple rhyme:

む す め ふ さ ほ せ

mu su me fu sa ho se

Which actually spells a mnemonic sentence in Japanese:

娘房干せ

“Daughter, dry the bunches [of flowers, grapes, whatever]

However, for learning all 100 poems, the Seattle Karuta Club pointed me to some helpful resources online:

- Karuta SRS

- LearnKaruta is a great starting point in general

- This site divides the kimari-ji by initial letters, and has good visuals.

- There are mobile apps too, though many have advertisement banners and such. You can search for “hyakunin isshu” in your favorite app store.

There are a lot of helpful charts and explanations in various Japanese sources (this is a great example), since it’s a popular pastime, but if you’re still learning hiragana and not familiar with Japanese language, you may need to stick with English-sources for now.

For my part, I started trying out some things at home. Since I don’t have a goza mat yet, I just grabbed one of my battle-map playmats I use for Dungeons and Dragons, and used that as a play area:

I started practicing with batches of 5-10 karuta cards at a time, starting with the 1-character and 7-character kimari-ji, since they are both fewest in number.

But then I started sprinkling poems in that I just happened to like. Since I spent so much effort memorizing poems previously, I picked out another 10-15 that I liked, and mixed them in anyway.

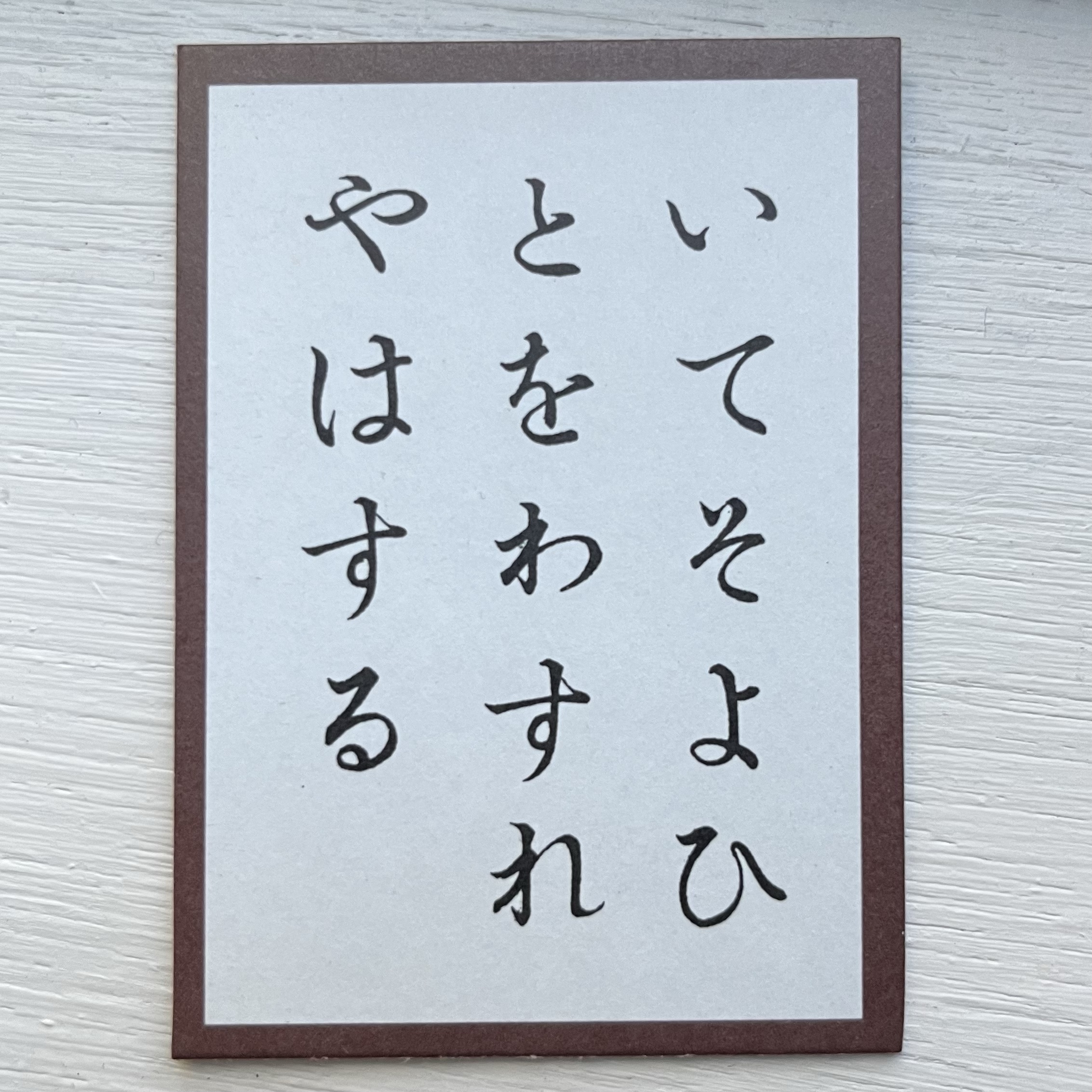

Then, I started making my own flash cards using Anki SRS using a format similar to this site:

This is poem 9 by the way.

As you can imagine, there’s many ways to learn the kimari-ji. The sky’s the limit as they say. Find something that works for, or keep experimenting until you master all 1️⃣0️⃣0️⃣ poems! Once you’ve done that, the game really starts to open up.

Anyhow, my goal is to try to learn at least half of the cards reliably before the next meeting of the Karuta Club in September. It won’t win me any matches, but it will build a foundation for (hopefully) future wins.

Good luck, and happy Karuta play!

1 There are a few exceptions to this in the Japanese, mostly in the revised modern spelling, but not worth calling out here.

Leave a comment