On a quiet Saturday afternoon, the first in a long time, I caught up on some reading and continued to read through my book about the Hyakunin Isshu (mentioned here): the Hyakunin Isshu Daijiten.

In one chapter, the book discussed a special artistic collection of the Hyakunin Isshu called the Kōrin Karuta collection (kōrin karuta, 光琳カルタ) which was painted by the famous artist Ogata Kōrin (尾形光琳, 1658-1716). The featured image above is one of his famous paintings depicting irises in a field (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons).

I had a hard time finding available images of the Ogata Kōrin collection of cards, but you can see an example at the Tengu-do homepage. There’s a few things that make this collection noteworthy among the long history of the Hyakunin Isshu….

First, the cards use a gold background, instead of white or off-color white. If you look at Ogata’s other paintings, this is a common technique that he used, so it makes sense.

Second, and more significantly, the torifuda cards are painted as well. Whereas the yomifuda cards have portraits of the poets (with some subtle details we’ll talk about below), modern torifuda cards only have the text on them. Ogata decorated the torifuda cards using scenes that matched the poem.

For example, poem 100 (ももしきや) is shown here on the Tengu-do website. The corresponding torifuda card shows the eaves of a palace since the poem is about the declining condition of the Imperial palace amidst political strife. Poem 35 (ひとはいさ) is shown here. Since the poem is about the first cherry blossoms in spring, the torifuda card depicts cherry blossoms. And so on.

Third, the cards were larger in size than a standard karuta card used today. Perhaps the cards were not meant for playing, but as a medium of art.

Also, I realized that the illustrations of the poets looked awfully familiar. My first karuta set uses the same Ogata illustrations, even though the torifuda are not illustrated, and the card background is plain white versus the original gold color.

Even the paintings of the authors has some pretty interesting qualities to them. Using my own set, let’s take a look at a few notable quirks.

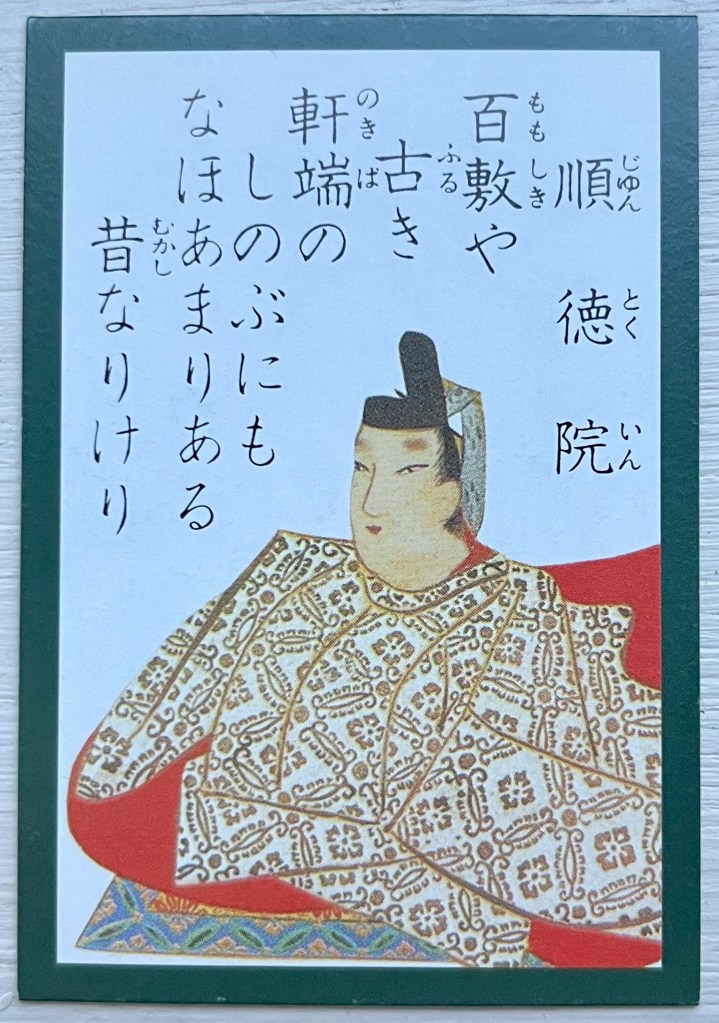

First, the “emperor” cards (cards where the poet was a reigning or retired emperor) have them seated on a straw mat with a brocade edge, a sign of authority. None of the other poets have this, even if the poet was a high ranking officials in the court. Here are the cards for Kōkō Tennō (“Emperor Koko”, poem 15) and Juntoku-in (“Retired Emperor Juntoku”, poem 100):

Second, while most poets’ faces are visible, the card for Shokushi Naishinnyo (“Imperial Princess Shokushi”, poem 89) completely hides her face. Why is that?

Evidentially, Princess Shokushi was quite beautiful, and Ogata didn’t want to leave her open to criticism or scrutiny, so he hid her face to protect. In some versions of the Kōrin Karuta set, Ono no Komachi’s (poem 9) face is also hidden.

The Kōrin Karuta collection isn’t the only famous illustration of the Hyakunin Isshu, and in time I hope to highlight others.