Centuries before the Hyakunin Isshu was compiled and before official Imperial anthologies such as the Kokin Wakashū were promulgated there was the Manyoshu (万葉集) or “collection of ten thousand leaves”.

The Manyoshu is the oldest extant poetry collection, completed in 759 CE for the pious Emperor Shomu, and has much that resembles the Hyakunin Isshu, but also much that differs. I have been reading all about it in a fun book, which is in the same series as this one.

The Manyoshu was purportedly compiled by one Ōtomo no Yakamochi (大伴家持, 718-785), author of poem 6 in the Hyakunin Isshu, but it’s also likely that he only compiled the collection toward the end, and that others were involved too.

Sadly, English translations are very few in number and usually quite expensive. Translation the Hyakunin Isshu hard enough, and this is even more true with a large volume like the Manyoshu.

Format

The Manyoshu is a collection of poems from a diverse set of sources, including members of the Imperial family and the aristocracy, but also from many provinces across the country and people from many walks of life. In fact, 40% of the poems in the collection are anonymous, with sources unknown. It also includes a few different styles of poetry:

- 265 chōka (長歌), long poems that have 5-7 syllable format over and over (e.g. 5-7-5-7-5-7…etc), until they end with a 5-7-7 syllable ending. These are often read aloud during public functions. Kakinomoto no Hitomaro (柿本 人麻呂, 653–655, or 707–710?), who wrote poem 3 in the Hyakunin Isshu, was considered the foremost poet of this format, but the longest was composed by one Takechi no Miko (高市皇子) at 149 verses.

- 4,207 tanka (短歌), short poems as opposed to the long poems above. The “tanka” style poems are usually 5-7-5-7-7 syllables long, and are what we see in later anthologies such as the Hyakunin Isshu. At the time, they were often included as prologues to long poems above. The Hyakunin Isshu is entirely tanka poetry, by the way.

- One an-renga (short connecting poem),

- One bussokusekika (a poem in the form 5-7-5-7-7-7; named for the poems inscribed on the Buddha’s footprints at Yakushi-ji temple in Nara),

- Four kanshi (漢詩), Chinese-style poems often popular with male aristocrats that contrasted with more Japanese-style poetry.

- 22 Chinese prose passages.

Additionally, these poems were often grouped by certain subjects:

- Sōmonka (相聞歌) – Originally poems to enquire how someone was doing, but gradually involved into couples expressing romantic feelings for one another.

- Banka (挽歌) – Funerary poems honoring the deceased.

- Zōka (雑歌) – Miscellaneous poems about many topics. Basically everything else that is not included into the other two topics.

Manyogana

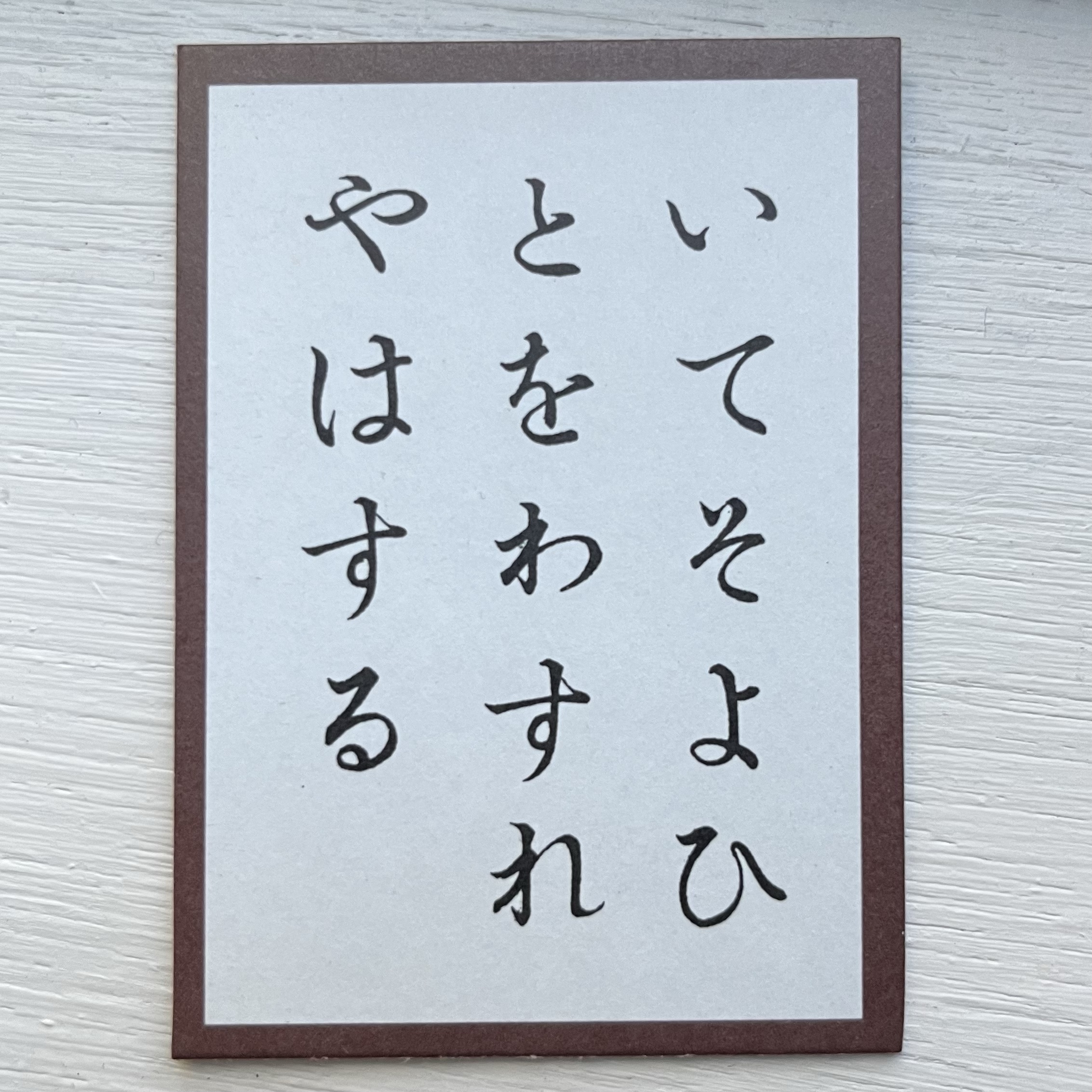

One of the interesting aspects of the Manyoshu compared to the later Hyakunin Isshu, and other related anthologies, is the written script used. When people think of karuta or Hyakunin Isshu, they think of the hiragana script, but the hiragana script didn’t exist in the 8th century when texts such as the Manyoshu, the Kojiki or Nihon Shoki. Such texts were composed using purely Chinese characters, but in a phonetic style native to Japanese later called Manyogana. Confusing? Let’s take a look.

The book above explains that in Manyogana, Chinese characters such as 安 and 以 are read phonetically in the Manyoshu as “a” and “i” respectively. Even modern Japanese people can easily intuit this.

Then you get more difficult examples such as 相 (saga) and 鴨 (kamo) in Manyogana. These are more obscure, but still possible for Japanese people to understand them.

Then you get much harder examples such as 慍 (ikari) and 炊 (kashiki).

And then you get even more difficult examples such as 五十 (also “i“) and 可愛 (just “e“). My wife who has an extensive background in Japanese calligraphy struggled with these.

In any case, words in Manyoshu were all spelled out using Chinese characters like this, with no phonetic guide. You just had to know how to read or spell them, and as you can imagine this was a clunky system. However, this system of phonetic Chinese characters is how the later hiragana script evolved.

Technique

When we compare the Manyoshu with the Hyakunin Isshu, there are many similarities. Both have tanka poetry (5-7-5-7-7 syllables), and cover a variety of topics. Further, both collections make good used of pillow words. In fact the same pillow words you see in the Hyakunin Isshu, such as hisakata no (poems 33 and 76), also show up centuries earlier in the Manyoshu:

| Original Manyogana | Modern Japanese | Romanization | My Amateur Translation |

| 和何則能尓 | 我が園に | Waga sono ni | Perhaps |

| 宇米能波奈知流 | 梅の花散る | Ume no hana chiru | the plum blossoms will |

| 比佐可多能 | ひさかたの | Hisakata no | scatter in my garden |

| 阿米欲里由吉能 | 天より雪の | Ama yori yuki no | like gleaming snow |

| 那何久流加母 | 流れ来るかも | Nagarekuru kamo | from the heavens |

This poem, incidentally was composed by Yakamochi’s father, Ōtomo no Tabito, when he organized a flower viewing party at his villa (book 5, poem 822).

Another commonality, the book explains, is the use of preface verses or jo-kotoba (序詞) where the first verses are just one long-winded comparison to whatever comes after. Poem 39 in the Hyakunin Isshu is a great example of this since the first 3 verses describing various grasses are all just setting up the point: that love is hard to hide.

The Manyoshu used this technique as well:

| Original Manyogana | Modern Japanese | Romanization | My Amateur Translation |

| 千鳥鳴 | 千鳥鳴く | Chidori naku | Just as the plovers’ cries |

| 佐保乃河瀬之 | 佐保の川瀬の | Sabo no kawase no | along the wavelets |

| 小浪 | さざれ波 | Sazare nami | of the Sabo river |

| 止時毛無 | やむ時もなし | Yamu toki mo nashi | never end, |

| 吾戀者 | 我が恋ふらくは | A ga ko furaku wa | so too are my feelings of love. |

Historicity

Similar to the Hyakunin Isshu, the Manyoshu covers a fairly broad span of history, but much of it is now pretty obscure to historians. Even so, the poems in the Mayoshu can be grouped somewhat reliably into 4 specific eras:

- first half of 5th century to 672 CE, starting with the reign of Emperor Nintoku onward.

- 672 to 710 CE

- 710 to 733 CE

- 733 to 759 CE

These periods mostly coincide with certain authors who contributed poetry, but also appear to have breaks due to historical events such as conflicts, temporary political upheavals, etc.

Differences with the Hyakunin Isshu

Although there are many commonalities between the Hyakunin Isshu and the Manyoshu, there are also differences. The most obvious is that the Manyoshu is a mixed-format collection, so it includes poetry other than Tanka style. Another difference is its broad sources for poetry, not just contributions by the elite aristocracy.

However, the book above notes that on a technical level there are other differences.

For example, the use of “pivot words” frequently used in the Hyakunin Isshu ( poems 16, 20, 27, and 88 for example) is a technique that is almost absent in the Manyoshu. Similarly, puns are also rarely used.

Legacy

As the largest and earliest extant poetry collection, it set the standard for Japanese poetry that people were still studying and emulating centuries later. Poems such as 22, 64, and 88 are all examples that use themes or poetic styles that closely resemble poems in the Manyoshu.

Further, compared to more polished anthologies that came later, the Manyoshu’s bucolic and unvarnished content has often been revered by later generations (including Japanese nationalists and Shinto revivalists in the 19th century) for getting to the “heart of Japanese culture”.

The book has been a great read, with amazing illustrations, and it helps show how the roots of the Hyakunin Isshu, including a few of its early authors, lay centuries earlier in the Manyoshu.

Leave a comment