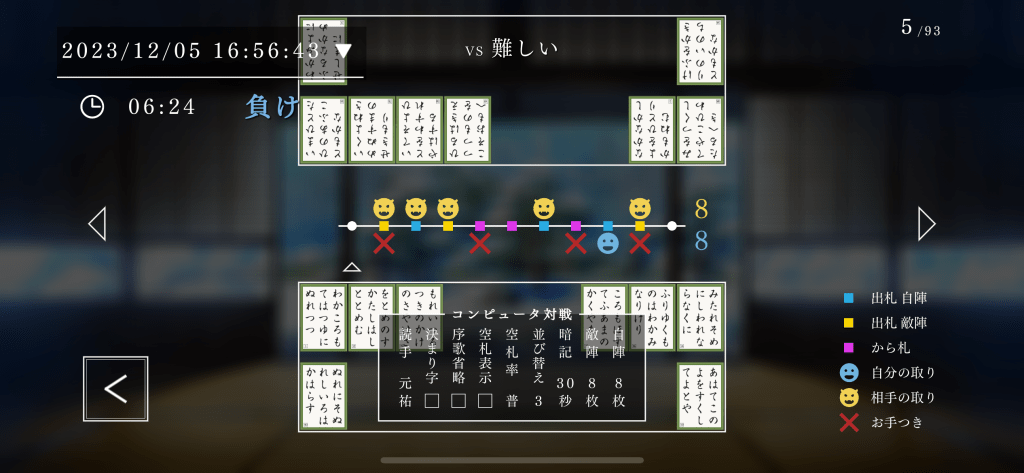

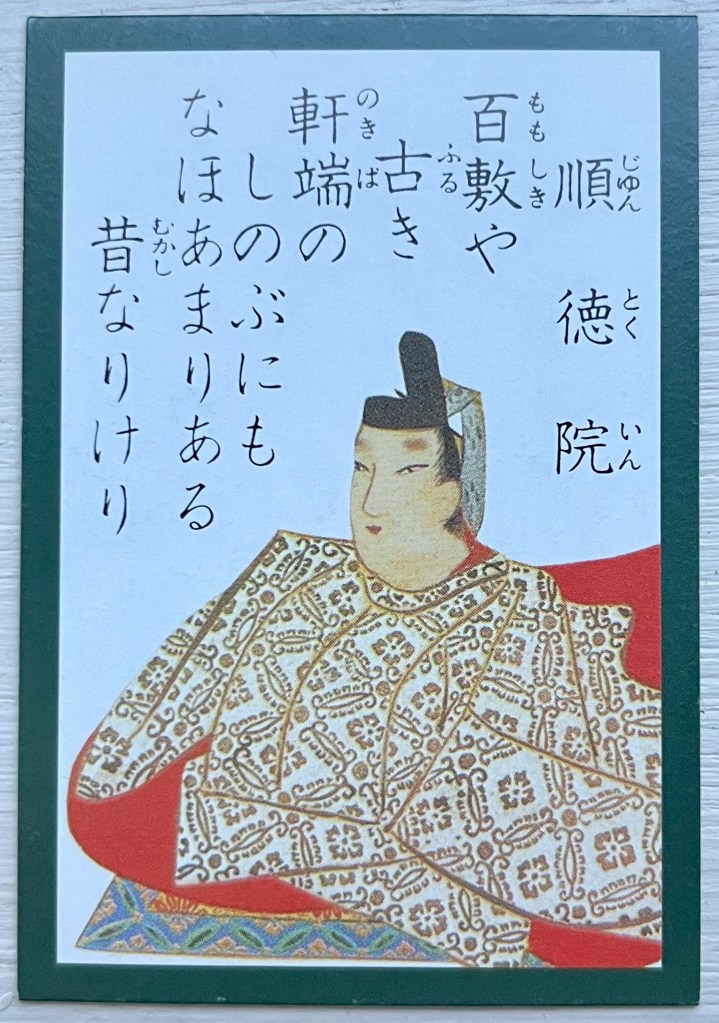

One of the first challenges when you start a game of karuta is to figure out where to put your cards. You’ve been dealt 25 torifuda cards out of 100 total (or 8 if you’re playing online) and they need to be arranged somehow in 3 rows (2 online) such that you can remember where they are, and hopefully make it harder for your opponent to take your cards.

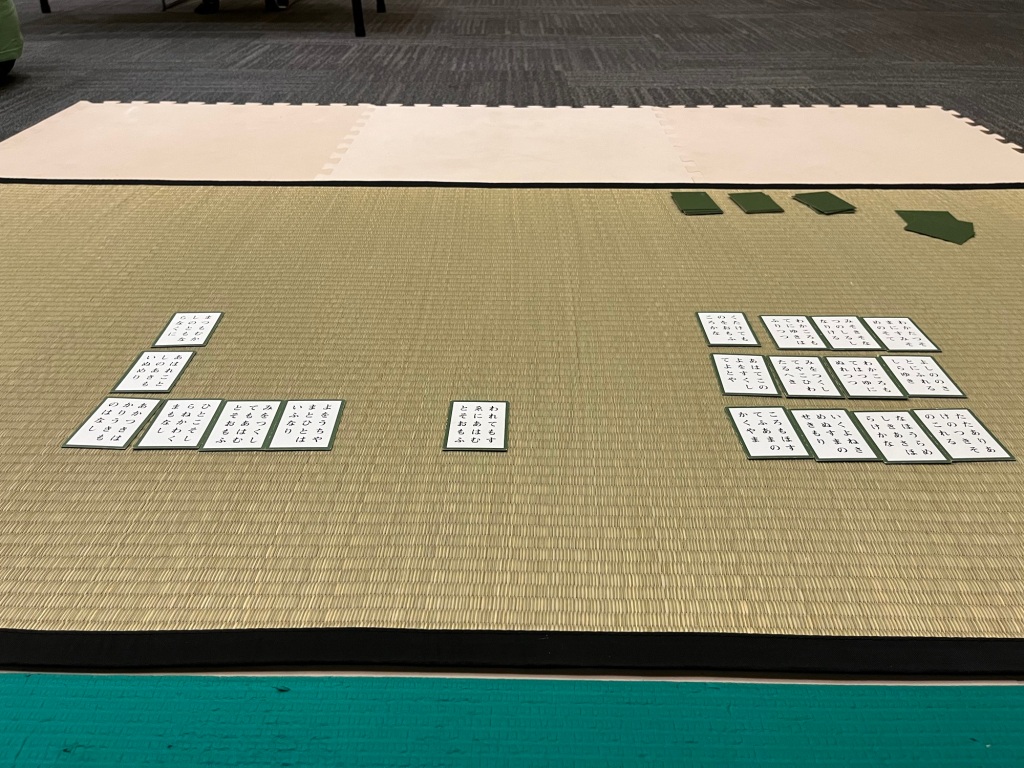

An arrangement of cards, might look something like the picture above: 3 horizontal rows, 1cm between them, and cards arranged across these three rows usually clumped into corners.

Sounds easy … right?

Nope.

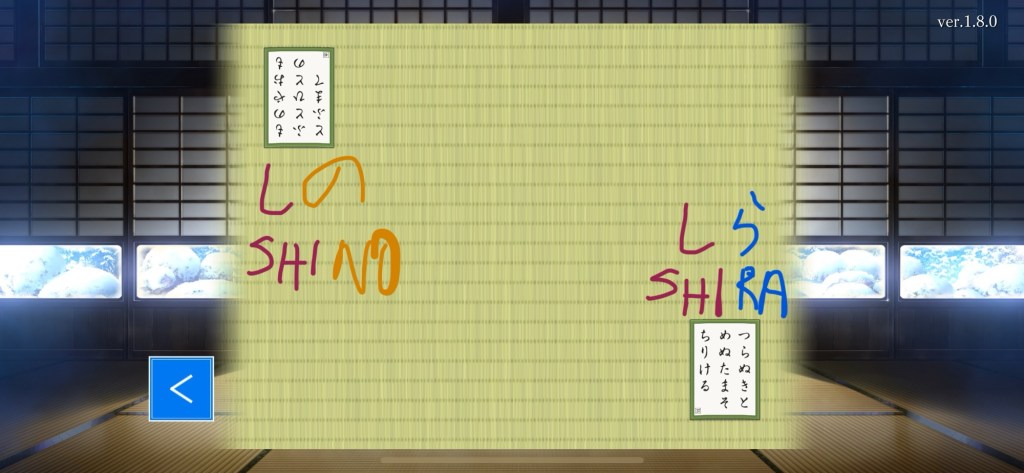

The concept of card position or tei-ichi (定位置) has plenty of strategy, and also plenty of personal habits. The first time I ever played, I didn’t know any of this and so my tei-ichi made no sense. I called it the “chaos strategy” as a joke:

It wasn’t even using the correct arrangement or spacing, but I lost 25-0 so I guess it didn’t matter. In time, my arrangement got somewhat better:

In any case, along as you adhere to the basic dimensions of the game layout, you can arrange your cards anyway you like. But also keep in mind that you have constantly remember the current board state (i.e. where every card is) because they often move around as the game progresses. This takes considerable concentration and good mastery of the kimari-ji.

During the start of the match, a lot of people, myself included, like to place their favorite cards in certain areas, or arrange them in a certain way to help relieve the pressure of memorizing so many card positions. I am told by much better players that if you play an opponent enough times you’ll start to figure out where they usually put their cards and can anticipate this (making it easier to remember board state). I have yet to reach this state.

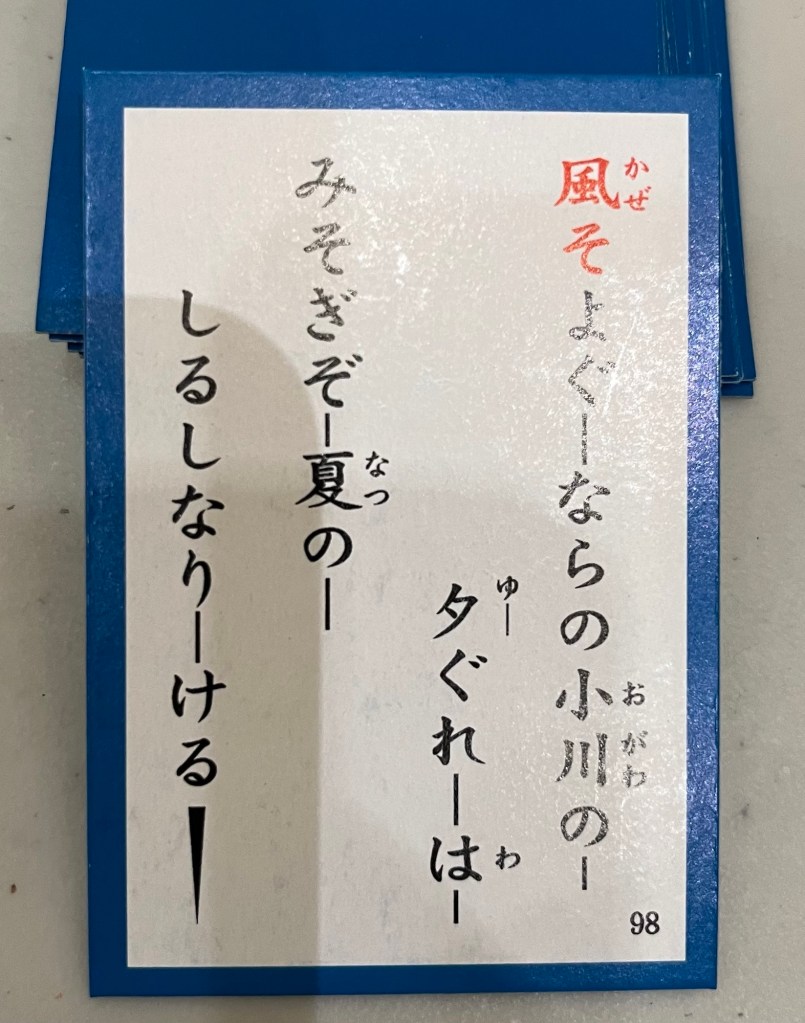

If you watch the anime Chihayafuru1 you may recall that the chubby kid Nishida2 explains some basic tips for good tei-ichi:

- Keep the one-syllable kimari-ji cards on the row closest to you. SInce they are taken very quickly, that little extra bit of distance may help you.

- Keep the tomofuda (友札) cards, the ones with similar kimari-ji, separate from each other. We’ll get to that in a moment.

These are merely suggestions though. Some players seem to prefer to a more offensive style of play, where they focus more on getting their opponent’s cards and less on their own card arrangement. Other players prefer a more defensive style where they focus on taking their own cards first, and making it as difficult for the opponent as possible.

A very common strategy I see for new and veteran players is to keep your tomofuda together (despite Nishida saying not to). For example, if I have the two cards starting with kono (poem 24) and konu (poem 97) as their kimari-ji, I might go ahead and keep them together. That way, I know where all my “ko” cards are. If I also have koi, then I might put all 3 together.

On the one hand, it’s easier for me to remember. On the other hand, your opponent will likely notice this too, and it makes their job easier.

You can also do as Nishida suggests and intentionally keep them separate. More work for you, but also more work for them.

Notice too that people often keep their cards towards the left and right edges. As with the single-syllable kimari-ji, that extra bit of distance makes it harder for your opponent to reach over and take the card before you do. In close games every bit counts.3

By the way, it is possible, within certain rules and customs, to rearrange cards into new positions during the match. People often do this in the late game when they have only 3-4 cards left and just want to clump them into a single spot, but this is a personal choice. I am told that moving your cards too often is frowned upon. However, if a card in between others was taken, it’s quite alright to shuffle the remaining cards on the row to the edges to take its place (keeping everything neat and tidy).

Since I am kind of a lousy player, I am not adverse to sharing my strategy here, but keep in mind that it is neither expert strategy, nor is it static. It changes and evolves as I gain more experience.

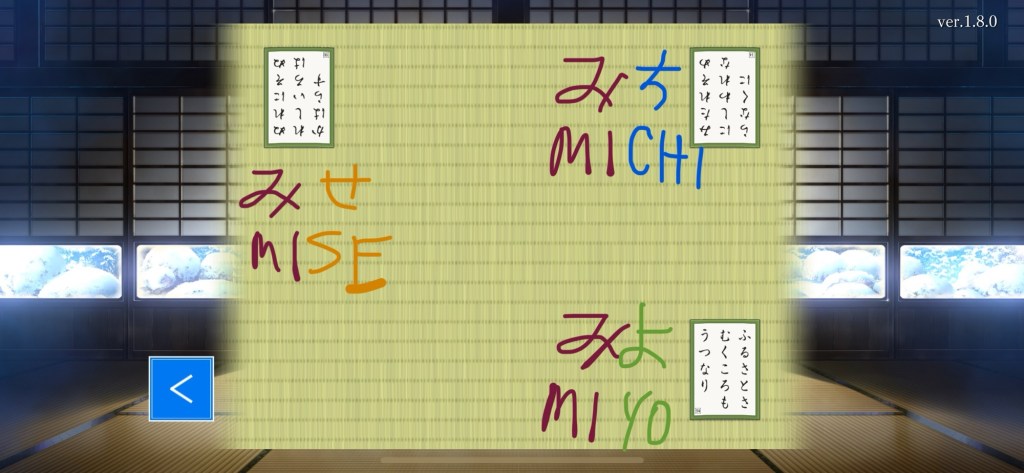

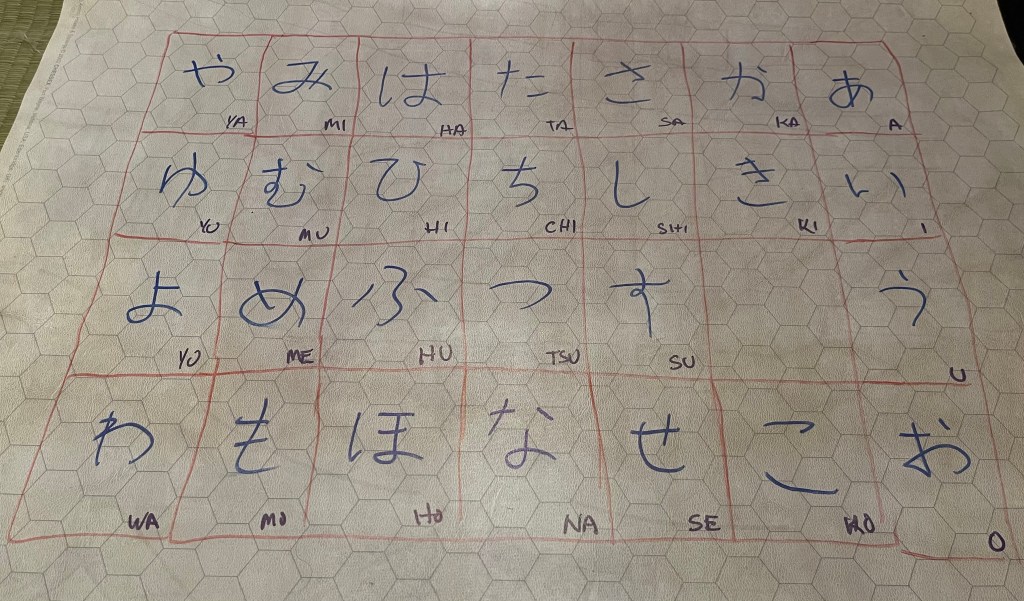

Because of my experience with Japanese language, I like to arrange mine based on columns of the hiragana syllabary, not so much tomofuda:

For example, if I have cards that start with “a” or “i” kimari-ji, for example, I’ll lump them together since they’re in the same column of the hiragana chart. I often group “yo”, “ya” and “yu” together similarly. Of course, I often have tomofuda among them, but that’s not always the case. I have areas where I almost always lump the “a”-row cards, the “ya”, “wa”, and “mi” cards, the “o” cards and so on. It can vary quite a bit depending on which cards I get at the start of the game, but I’ve definitely evolved some habits, for better or worse.

If I have too many cards like this, then I might break them up into two groups so they don’t clump too much. If I get seven “a”-row cards, it’s a bit silly to keep “all my eggs in one basket”.

I do follow Nishida’s advice and keep my one-syllable cards in the corners, but that’s almost a universal strategy, I’ve noticed. Even if you’re reflexes aren’t great, that extra little bit of distance away from your opponent can help.

Further, sometimes, if there’s a card that I am pretty comfortable with, such as the ooe card (poem 60), wasura (Poem 38), or shira (poem 37), I like to isolate it in the middle of the back row. It’s very easy for me to grab, and its unique position is easy for me to remember. Sometimes I do that with the iconic chiha card (poem 17) as well, though it rarely works for me. Of course, this strategy sometimes backfires too.

Thus far, we’ve talked a lot about starting positions. Let’s talk about things moving around.

As cards move around either due to penalties, or because a card from the opponent’s side was taken, things will move around. This can make things hard to remember when you’ve barely got a grasp on where the cards were previously, and that can lead to penalties. One advice I found in Japanese was to send cards to your opponent that have lots of impact (i.e. easy to remember), so you have an easier time remembering the new board state. You can also send tomofuda cards to your opponent so that they are forced to keep them together, or keep them separate. You can also break up your own tomofuda this way.

In any case, as gameplay continues, I try to scan and rescan the board state over and over again to refresh the current card positions. I even close my eyes and try to remember the board state in my mind without any visual distractions. I found closing my eyes to be especially helpful. I think in Chihayafuru, the kids even played a game where the cards were face-down, so the entire game was done from memory. I haven’t tried this yet, but might try it with a smaller set of cards someday.

Based on limited experience, I have noticed that if I stay focused and keep re-scanning the board state over and over, while paying close attention to what the reader is reciting, I tend to play better. When I lose focus, everything goes off the rails.

So, initial card position is something important to consider, but even more important is updating that “mental map”, and of course good listening skills.

Good luck!

P.S. This is pretty amateur advice, so take this with a grain of salt.

1 To be honest, I never finished season one of Chihayafuru. I watch plenty of Japanese TV, but I just don’t watch anime very much. I don’t really watch Ghibli movies either. However, in a feat of hypocrisy, I love Fire Emblem: Three Houses.

2 I forget his English nickname, but his Japanese nickname is Nikuman-kun where nikuman are just the Japanese version of Chinese hum-bao. Anyhow, you probably know the guy, right? Right? 😅

3 If you’re playing against me though, you’re probably going to win. I think my win rate is about 2-3% thus far.