No one likes getting rejected. Even back in classical Japan:

| Japanese | Romanzation | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| 今来むと | Ima kon to | It was only because you said |

| いひしばかりに | Iishi bakari ni | you would come right away |

| 長月の | Nagatsuki no | that I have waited |

| ありあけの月を | Ariake no tsuki wo | these long months, till even |

| 待ちいでつるかな | Machi idetsuru ka na | the wan morning moon has come out. |

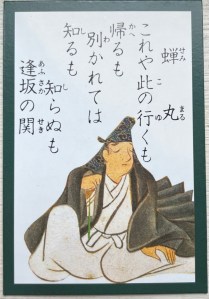

This poem was composed not by a woman as one would expect, but by a Buddhist priest named Sosei Hōshi (素性法師, dates unknown), or “Dharma Master Sosei”. He was the son of Henjō (poem 12, あまつ) before Henjō took tonsure. In fact, when Henjō did become a monk, Sosei was obligated to do the same.

Nonetheless, Sosei kept busy. He worked in the Imperial Court and was a priest, and a prolific and popular poet. He kept a salon of fellow poets including Ki no Tsurayuki (poem 35, ひさ) and Oshikochi no Mitsune (poem 29, こころあ). Both men were tasked with compiling the imperial anthology, the Kokin Wakashū, and Mostow points out Sosei is heavily represented in there. Coincidence? My new book suggests not. To his credit, Sosei is also one of the Thirty-Six Immortals of Poetry.

As we’ve seen with other poems from this earlier era, it was common to write about poetry themes, and to write from a role outside one’s own. So, for a monastic to be writing from the perspective of a lonely woman wasn’t unusual.

This poem is interesting because it seems to happen in one night, or a long period of time. It is a mystery. Mostow explains the contradiction in this poem between the “one long night” and “months” as being an issue of interpretation. Though most people assumed it was a long Autumn night, Fujiwara no Teika (poem 97, こぬ), the compiler of the Hyakunin Isshu anthology, felt it was more like a long passage of time.

P.S. Photo above is a Japanese calendar we have a home. More on that in a related post in my other blog.