Hello readers and happy 2026! Today I wanted to share something that is both familiar and yet new: Iroha Karuta (イロハカルタ).

I’ve talked about the game of karuta before, but this is in the context of Hyakunin Isshu poetry (which is the main topic of this blog 😉).

However karuta (from Portuguese carta) includes many similar games, not just the Hyakunin Isshu poetry. Many such games use a format called Iroha Karuta.

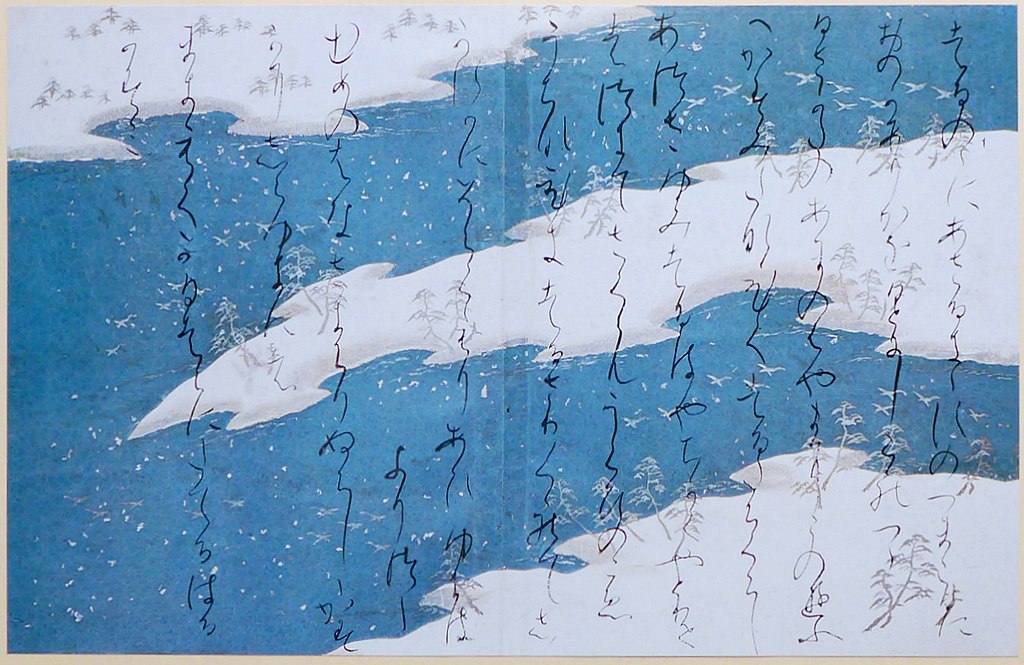

The iroha poem is a very famous poem, possibly composed by Kakinomoto Hitomaro (poem 3, あし) which uses exactly one of each Japanese kana syllable to form a lovely waka poem. It’s frequently used to alphabetize things in Japan, assign seats, etc.

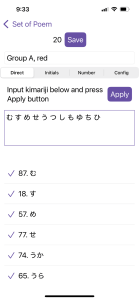

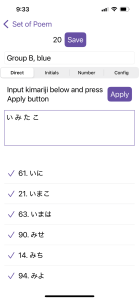

So, in the same way, karuta cards can be organized by Iroha letters too. This is an easier game than Hyakunin Isshu karuta because instead of learning the poems, their verses, etc., you just need to know the basic Hiragana syllabary. Then, when cards are read, you are listening for the first syllable and find the matching card.

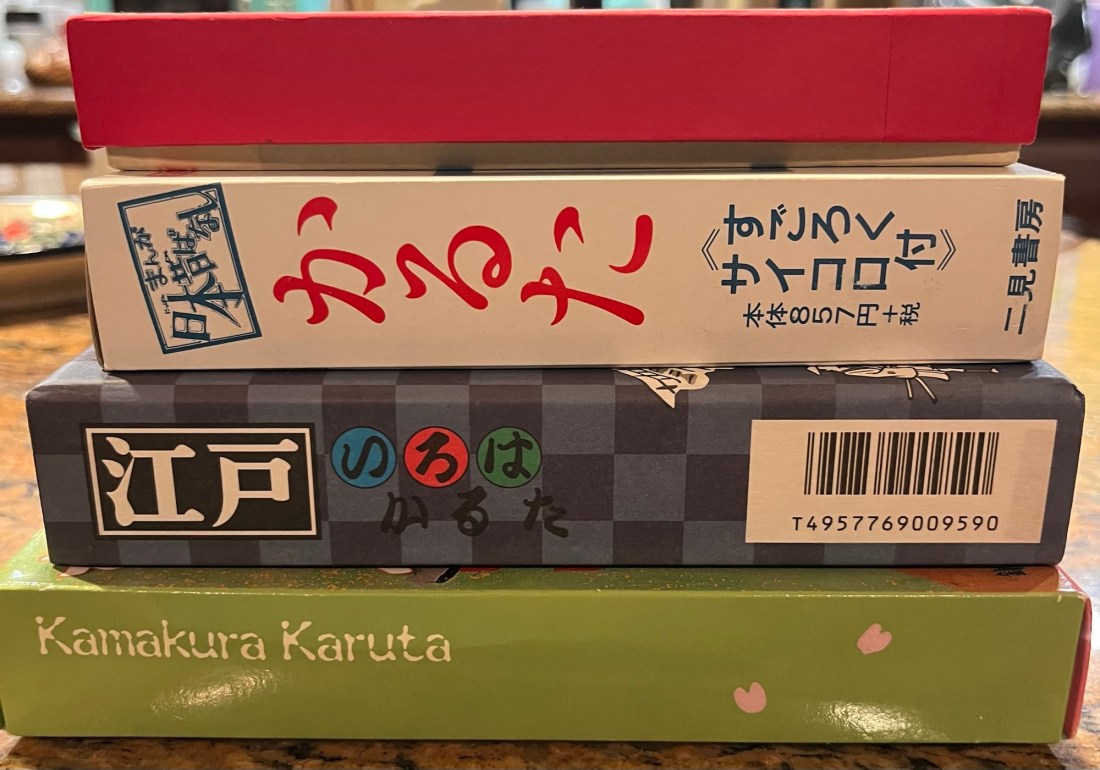

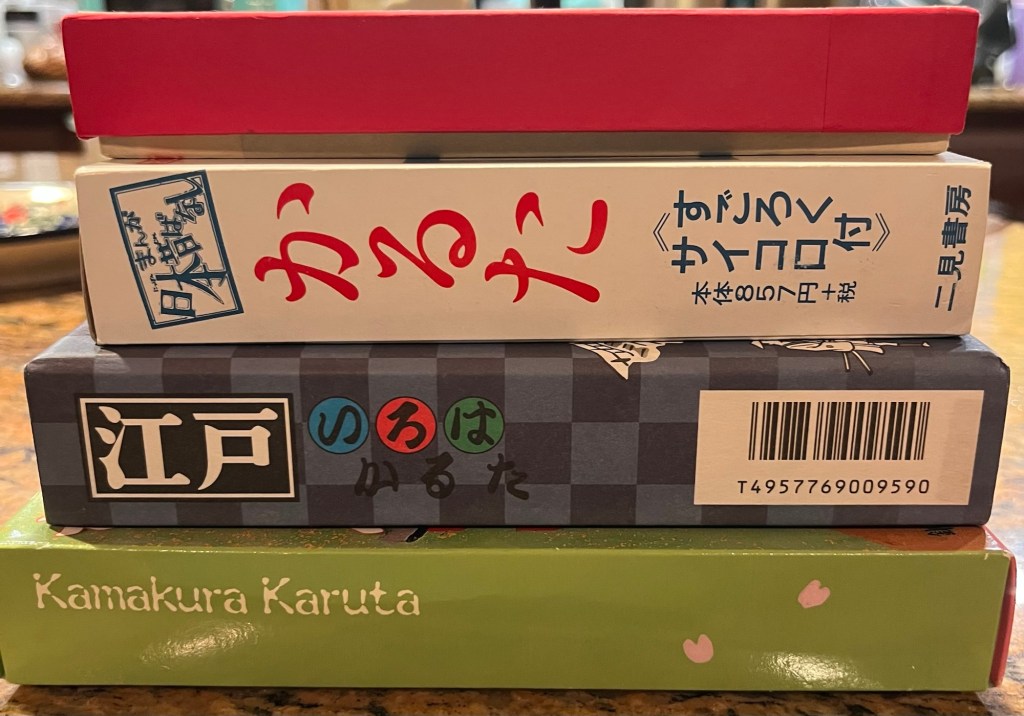

Over the years, my in-laws have sent us various karuta sets to my kids:

… but we didn’t really use them until recently. My youngest child understands enough Japanese now that we can play as a family.

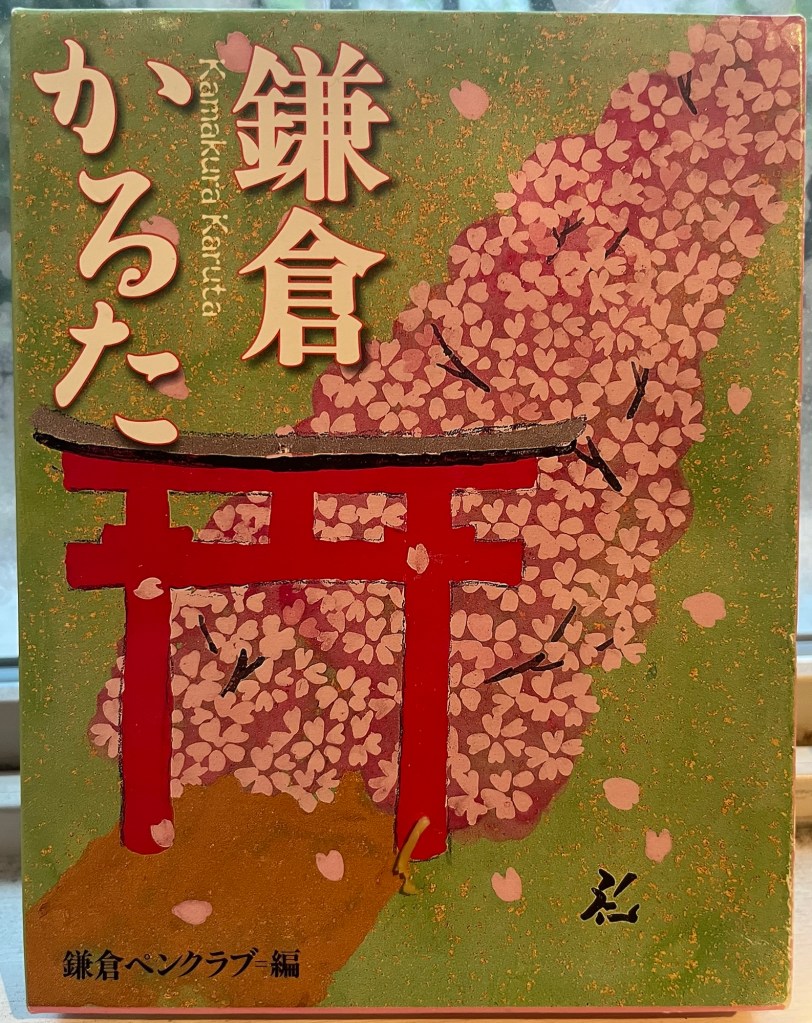

Karuta in general is often played just after Japanese new year, so this year we finally opened some of our old sets and played them one by one. My favorite set is this one:

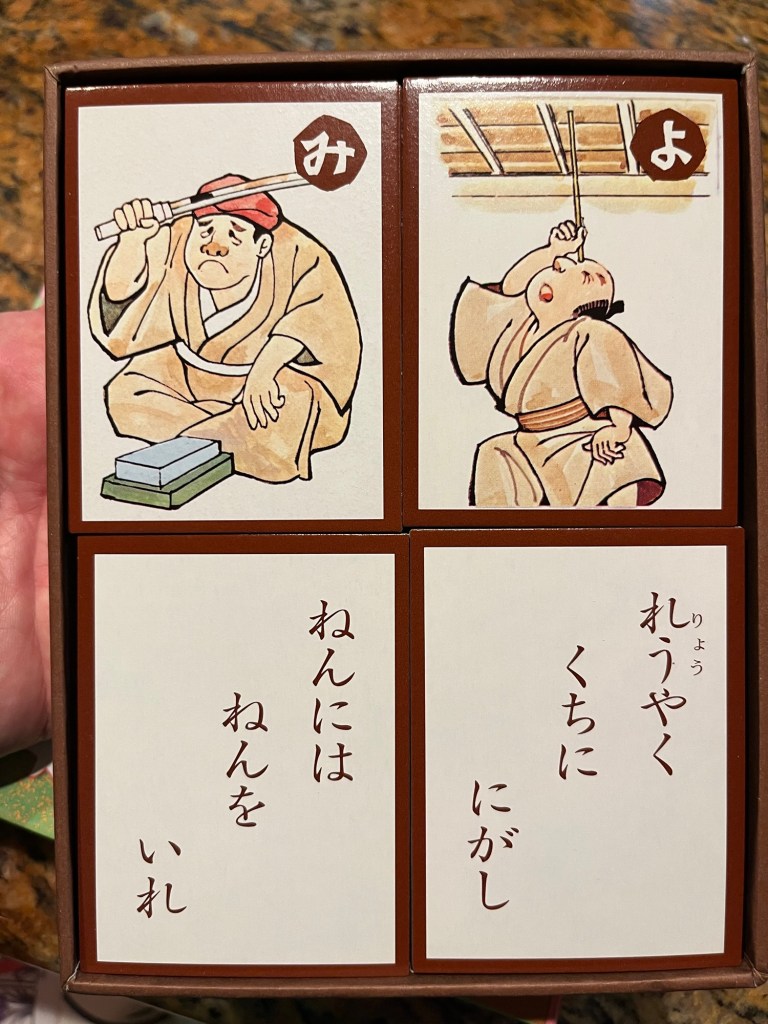

This set features the city of Kamakura, both past and present, using amazing artwork contributed by local artists. Sadly it is not sold anymore. The contents are below:

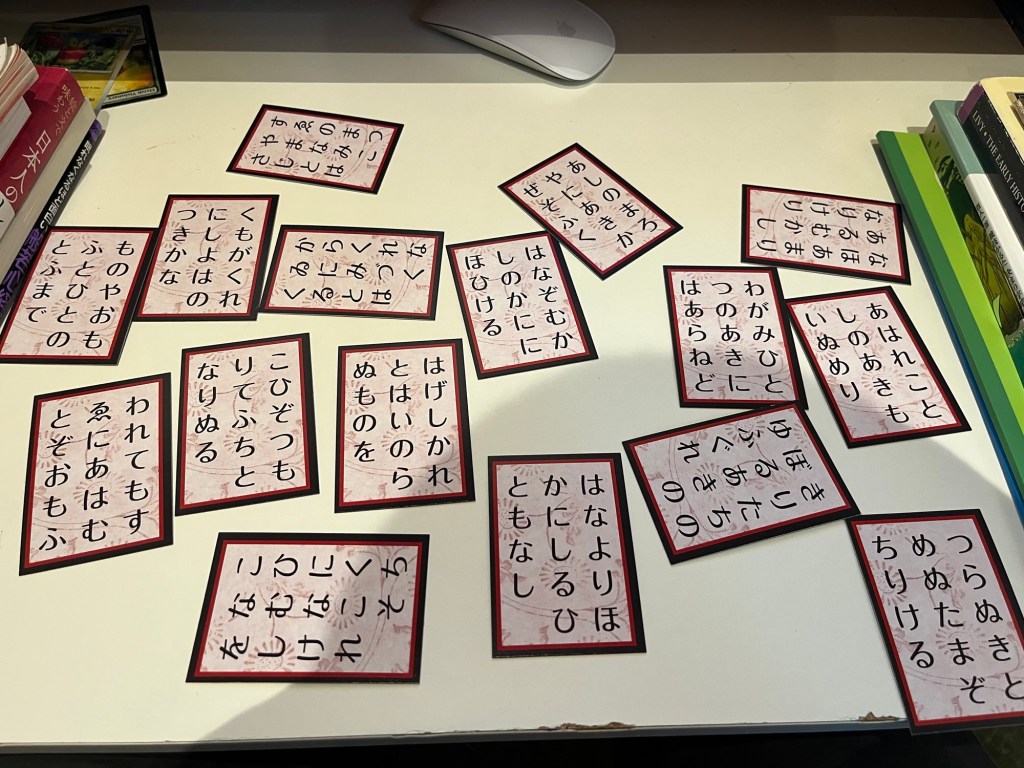

Similar to Hyakunin Isshu karuta, the cards are divided between “reading” cards (yomifuda, 読み札), and cards to take (torifuda, 取り札), with some short verses written on them. You lay out the cards like in chirashi-dori style (i.e. just spread around between players), and someone reads the cards (a.k.a. yomite 読み手) while other players try to find and take the card based on the first syllables.

The difference is that the artwork is on the torifuda cards, and you don’t have to memorize kimariji. The two cards on the left are related by the letter う (“u”) for uguisu, a famous bird in Japan.

Some other examples we (apparently 😅) own:

The theme of this one is old Tokyo (Edo 江戸) and features proverbs from back then.

This set above features famous Japanese fairy tales from an old NHK series, and surprisingly includes romaji letters (maybe to help foreign players). It also includes dice for a sugoroku style game. We own the related book series, published by Kodansha with English translation, and I used to read them to my kids when they were little. So, these illustrations are very nostalgic.

One nice thing about Iroha karuta is that you can use any possible theme. A quick Google search shows many sets, with themes such as Kyoto (京), old proverbs, and modern silly ones too. I even found a karuta set for the Manyoshu (!).

Hyakunin Karuta, by comparison, has a more refined image but also has a steeper learning curve, even when playing casual style. So, if you’re looking to play a quick game of Karuta and can read hiragana (or find a set with romaji), Iroha Karuta might be a suitable game for you. Since I own both, I like switching between the quick-and-easy Iroha karuta games, and the more refined and ambient Hyakunin Isshu karuta.

Many of the same stores that sell Hyakunin Isshu sets also sell Iroha sets, so don’t hesitate to look. Happy gaming!