Happy Holidays, Dear Readers!

As I noted in my other blog, I am taking time off the rest of the year to rest, and catch up on nerd projects.

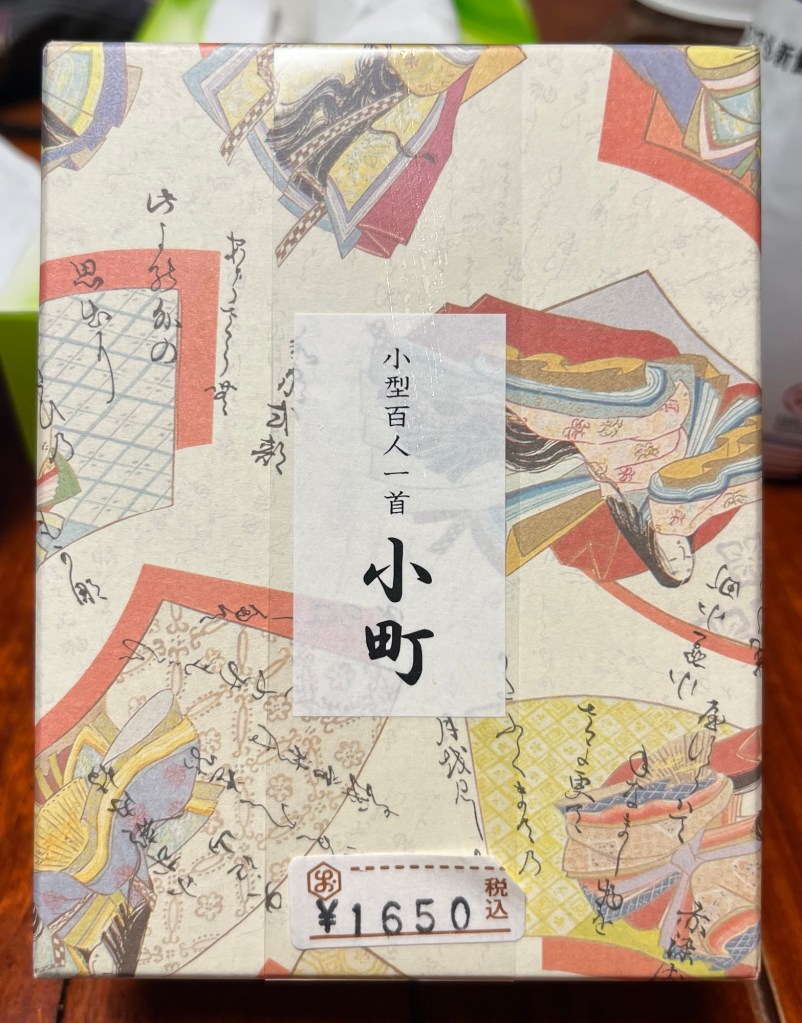

One last post before end of the year: I forgot to share this previously, but during the trip to Japan this summer, and on the same day we both visited the shrine to Sei Shonagon, and the site where the Hyakunin Isshu was compiled, I made one more stop: Nonomiya Shrine. The official website is here (English).

Nonomiya Shrine (nonomiya-jinja, 野宮神社) is a Shinto shrine that has been around since antiquity in west Kyoto within the bamboo forests. You can see it here on Google Maps:

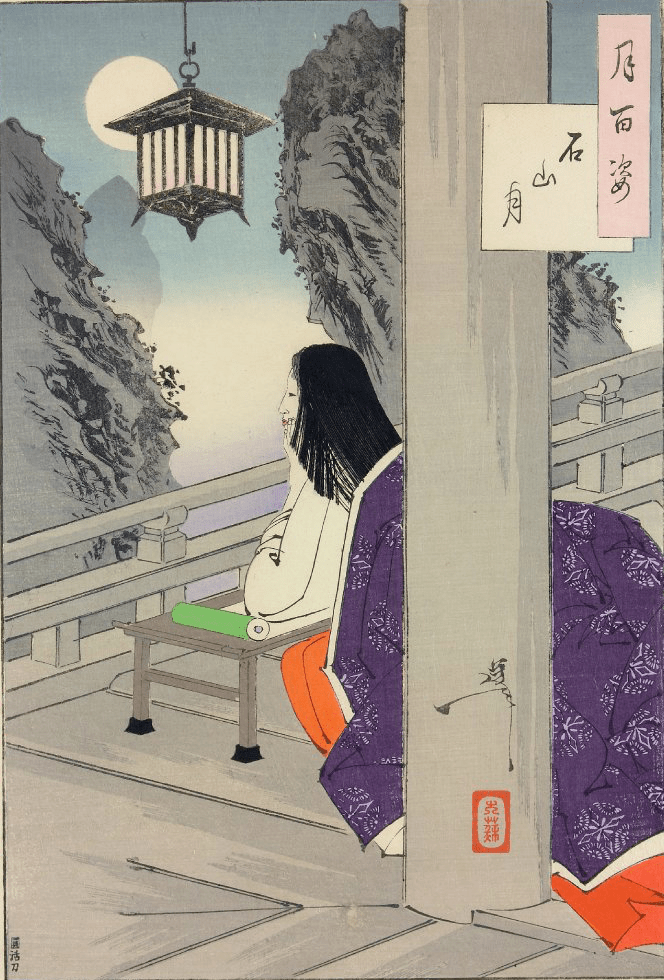

While it is not related to the Hyakunin Isshu, it is related to Lady Murasaki (poem 57, め), whom I wrote about here. You see, one of the most iconic chapters of the Tales of Genji, Lady Murasaki’s famous novel, the “Heartvine” (Aoi, 葵) takes place at Nonomiya Shrine. Here, Genji the protagonist meets Lady Aoi his future wife. So, Nonomiya Shrine is associated with romance and falling in love, or meeting one’s soulmate, and since it was already a fixture in Kyoto culture at the time, Lady Murasaki used it as the backdrop for this romantic encounter.

Even now, many people (both Japanese and tourists) come here to pray for love, and many of the omamori charms are focused on romance too. It’s nestled within the famous bamboo forests in the area:

I stumbled upon it by accident after leaving the aforementioned site where the Hyakunin Isshu site was compiled. My family was waiting for me, it was late in the day, and it was very hot and humid, so I didn’t stay very long, but I wanted to at least grab a few photos, and get an omamori charm.1

Anyhow, that’s it for the blog for 2024.

I wanted to end this post by saying thank you to readers. The blog has been been around since 2011 (with some major gaps in content), and with plenty of twists and turns, but I am happy to see that people are still actively reading it, and discovering the Hyakunin Isshu, Heian-period culture, and Japanese poetry overall.

See you all next year!

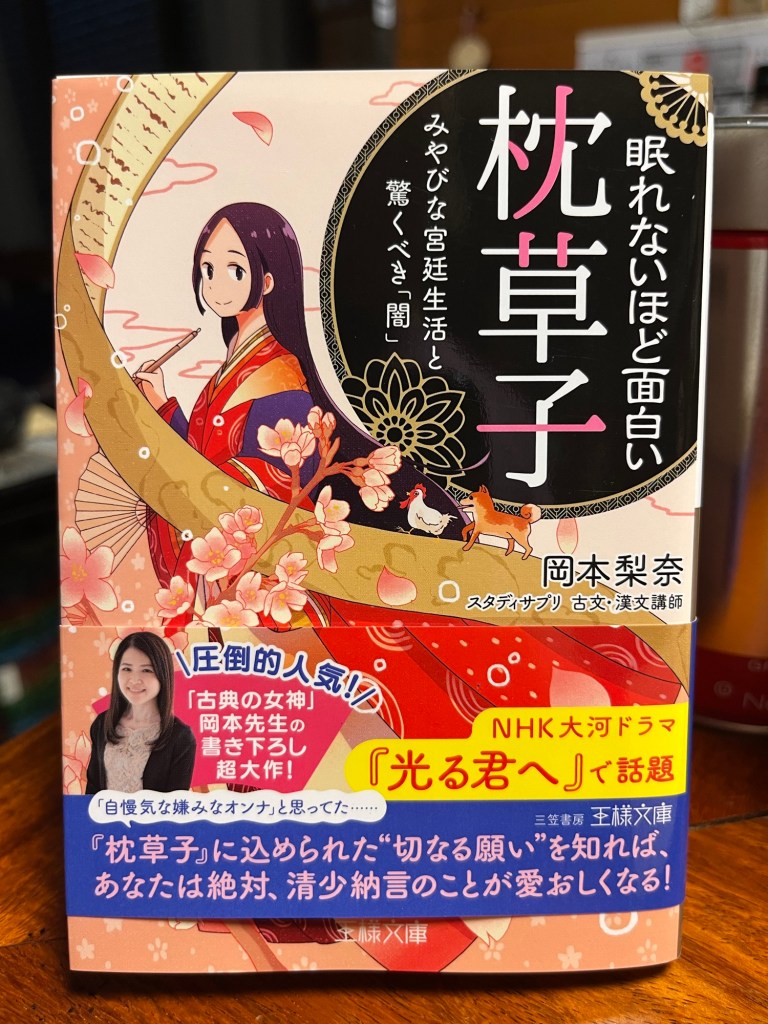

P.S. Not far away was an exhibit for the historical drama about Lady Murasaki as well.

1 Most of the charms are for en-musubi (縁結び), meaning finding a partner in life, but since I am already happily married, I looked for something general. I picked up a omamori for kai-un (開運), meaning “good luck”, but it showed the famous scene from the Tales of Genji where Genji and Lady Aoi meet at Nonomiya Shrine. I wish I remembered to take a photo sooner, but I already gave it to someone, and have no photos to show. 🤦🏼♂️

You can see it on the website here, the charm on the upper-right corner.