Hi folks!

I have been away for a while due to various life circumstances, but I’ve been wanting to share this news with readers.

The Japanese public TV station, NHK, broadcasts a new Taiga Drama (大河ドラマ) every year. These are big productions featuring some aspect of Japanese history, with big name actors and so on. I was very fond of the last one. Usually these cover periods of warfare or conflict, and male historical figures from Japan’s long history, but this year’s drama, titled Hikaru Kimi E (ひかる君へ, “Addressed to You [my dear Radiant One]”), features Lady Murasaki as the main character!

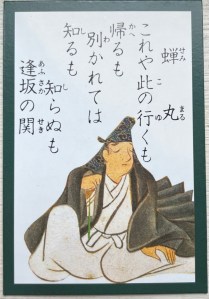

Lady Murasaki, poem 57 of the Hyakunin Isshu, needs little introduction. She composed the Tales of Genji, as well as her eponymous diary. She was the first female novelist in Japanese history, and has been a subject of interest ever since. The biographical details of her life are somewhat scant, unfortunately, and the drama does embellish quite a bit, including hinting strongly at a romance that probably didn’t happen in real life. My impression is that they are using romantic themes from her novel, the Tales of Genji, as the backdrop for the drama.

Nonetheless, I have been watching this series on Japanese TV1 and I enjoy it. It is somewhat different than past Taiga Drama, since it features a female main character, and this period of history (the late Heian Period), had little warfare, but it does have tons of scandal and intrigue as the Fujiwara clan tighten their grip on the reins of government. This drama is surprisingly risqué in parts, something you usually don’t see in a conservative Japanese drama. However, such scenes remind me more a more subdued Victorian romance than something in modern, American television.

That said, it’s a darn good drama thus far.

The drama frequently shows other people of the Heian period aristrocracy, many of whom were poets of the Hyakunin Isshu. To name a few who have been featured in the drama:

- Akazomé Emon (poem 59)

- Sei Shonagon (poem 62)

- Fujiwara no Kintō (poem 55)

- “Mother of Michitsuna” (poem 53)

- Takashina no Takako (poem 54)

I admit I am particularly fond of the character Sei Shonagon. In historical pop culture, Sei Shonagon and Lady Murasaki are treated as rivals as they were both famous writers of the same generation who belong to rival cliques in the aristocracy, but in reality they probably didn’t interact much. Nonetheless, they frequently talk in the drama, and the actress who plays Sei Shonagon, stage name is “First Summer Uika” (ファーストサマーウイカ), is a talented actress and total babe:

She is on Instragram, too:

First Summer Uika also recently visited a Shinto shrine devoted to Sei Shonagon in Kyoto called Kurumazaki Jinja (車折神社), which even sells Sei Shonagon charms (omamori):2

But I digress.

Because the drama features so many people related to the Hyakunin Isshu, the drama subtly works in many poems from the anthology. It’s been great to suddenly recognize a poem being recited, even if I am a bit slow to recall. The settings, costumes, and cast are all amazing, and even though the historicity is questionable, it’s been a great watch.

I really hope they eventually make an English subtitle version so people outside Japan can watch. The quality of Taiga Dramas are terrific, and they are well worth watching if you can.

Update: while visiting Kyoto in 2024, we found a local NHK display of the drama:

The second photo above is First Summer Uika as Sei Shonagon.

1 Sadly there are not foreign translations, and no subtitles, and it is not always modern Japanese, so I admit I struggle at times to follow the story. At other times, I can follow easily enough.

2 We are going to visit Japan again this year (the last for our teenage daughter), including Kyoto. Visiting this shrine is definitely on the itinerary, even thought it’s pretty small.