Some people give cards, some people give poems:

| Japanese | Romanization | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| 君がため | Kimi ga tame | For my lord’s sake |

| 春の野に出でて | Haru no no ni idete | I went out into the fields of spring |

| 若菜つむ | Wakana tsumu | to pick young greens |

| わが衣手に | Waga koromode ni | while on my robe-sleeves |

| 雪はふりつつ | Yuki wa furitsutsu | the snow kept falling and falling. |

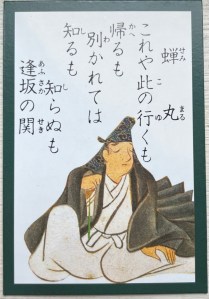

The poem was composed by a young Kōkō Tennō (光孝天皇, 830 – 887), Emperor Kōkō in English, who was traditionally, the 55th Emperor in Japan. He ascended the throne somewhat late (age 55) after Yōzei (poem 13, つく) abruptly retired. Koko’s own reign was similarly short, and power rested in the hands of his minister Fujiwara no Mototsune.

Nonetheless, Koko had a reputation for being a rather bright and easy-going youth. Despite being a Prince of the Blood, he was unlikely to inherit the Throne anytime soon (Yozei was still young, and Koko wasn’t directly related), and thus lived in obscurity. It’s said that he even had to cook his own meals. A poem mourning his passing states that his Imperial chambers still had black soot in them from cooking his own meals even after becoming Emperor.

The poem above is from those younger days, after he picked some wild flowers and herbs and sent them to someone as a New Year’s greeting. The poem was included in the offering. Young greens (wakana, 若菜) were the seven herbs used in the traditional holiday of Nanakusa on January 7th.

Even in the old Lunar Calendar, Nanakusa would fall around late January to early February. This helps to explain why snow was falling on the young prince’s sleeves.

Who was the recipient? It’s not known who received the poem and herbs, but since Nanakusa herbs are meant to bring safety, plus the language used (kimi ga tamé, きみがため), it definitely implies a young woman he cared about. ❤️ One theory suggests it was a beautiful girl named Tachibana no Kachiko (橘嘉智子), who was the consort of Emperor Saga.

This poem doesn’t use a lot of clever wordplays, the meaning is fairly straightforward, and it paints a nice image. It is a remarkably sweet, easy to grasp poem, that even foreign students of the Hyakunin Isshu can easily learn.