Language is not static. Any language that is spoken and used changes and evolves over time. The English language started as a dialect of German, but through a series of invasions, and innovations has a lot of elements that look French, with layers of classical Latin and Greek. The Greek language has been in continual use since the days of the ancient Mycenaeans to modern Greek people today, and ancient words can be found in use, yet at the same time modern Greek is smoother, more streamlined than its ancient Bronze-Age speakers. The ancient Chinese spoke in the Bronze Age doesn’t sound like modern Chinese, and yet the echos are still there both in the writing system, and how words a pronounced across various regional dialects.

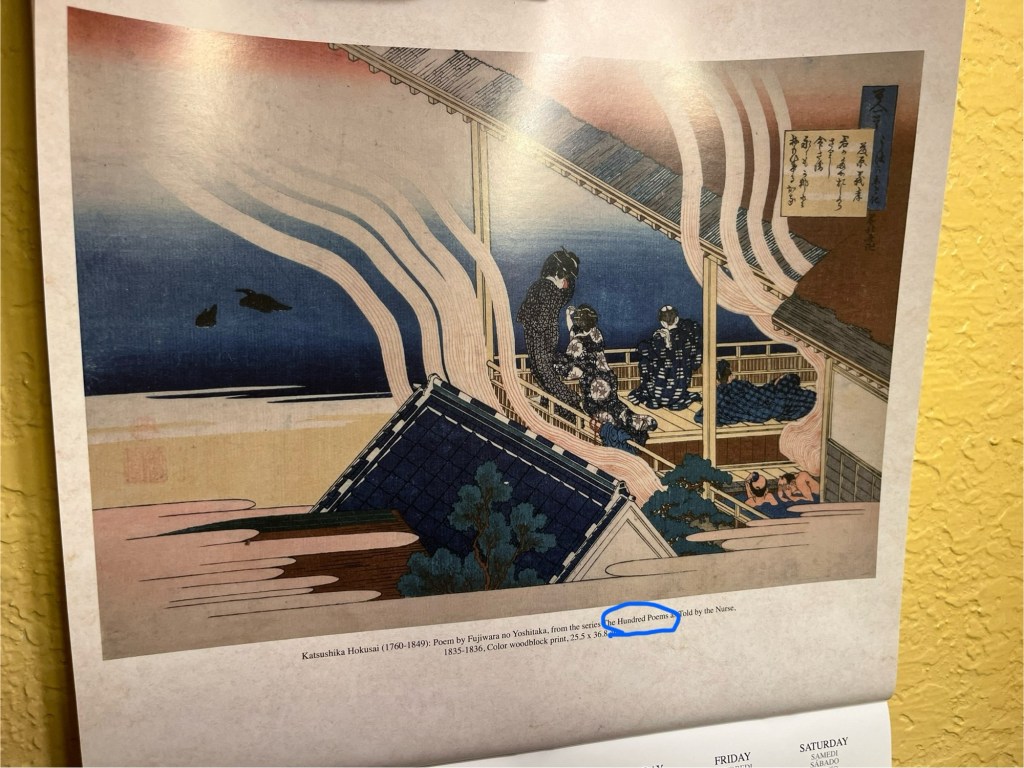

Japanese has been in continual usage for 2,000 years and it is possible to look at old poetry, such as the Hyakunin Isshu, and with a bit of effort still make sense of it as a modern, native speaker, or even as a language student. It also helps to explain why poems of the Hyakunin Isshu have such odd spellings compared to modern, standard Japanese.

And yet, Japanese has changed over time. Words and grammar have evolved, and so the poetry of the Hyakunin Isshu, as well as other writings of the time, look and sound in a certain way that might surprise modern people. This post is a brief exploration of the kind of Japanese used during the Heian Period (8th to 12th centuries) of Japanese history when most of the Hyakunin Isshu was composed. This period of Japanese is called “Early Middle Japanese” by English-speaking scholars, and chūko-nihongo in Japanese (中古日本語, lit. “middle-old Japanese”).

To give a quick demonstration, take a look at the video below, starting around 00:47. This is the first lines of the text, the Pillow Book, which we also talked about here.

A few things will jump out right away even to casual Japanese students.

First, all the “ha” syllables, namely ha (は), hi (ひ), hu (ふ), he (へ), and ho (ほ) are all pronounced with a “f” sound: fa, fi, fu, fe, fo. Even the subject-marking particle “wa” (also written as は) was pronounced as “fa” back then. Similarly, the “ta” syllables: ta (た), chi (ち), tsu (つ), te (て), and to (と) were all consistently pronounced as “t”: ta, ti, tu, te, to. In modern Japanese, people say omoitsutsu (思いつつ) to mean “even as I think about this…”, but back then the same word was pronounced omoitutu.

Finally there were more “wa” syllables back then, compared to now, and like the “ta” syllables, they were more consistently pronounced: wa (わ), wi (ゐ), we (ゑ), wo (を). In modern, Japanese, only “wa” is still pronounced with a “w” sound, and wi and we are no longer used, or pronounced simply as as equivalent “i” and “e”. Similarly, if you watch historical dramas, the old way of politely using the “negative”-form of a verb has shortened from nu (ぬ) to simply n (ん) : mairimasenu (“I will not come”) to mairimasen in modern-humble Japanese.

Languages tend to contract and streamline over time.

Using Greek language as a similar example, pronunciation of words in Homer’s Iliad sounds longer and clunkier than similar words in Koine Greek of the New Testament, and even more streamlined now in Modern Greek. Sanskrit in India was spoken 4,000 years ago, and lives on in many northern Indian languages such as Hindi, Marathi, Magadhi and so on, and each one looks like a smoother, simpler version of the old Sanskrit language. Japanese pronunciation of words has similarly contracted into shorter, smoother, more efficient forms.

What about grammar? That’s an interesting question. In some ways, the grammar of Japanese hasn’t changed all that much in the eons. Japanese verbs are inflected (like Latin, Greek and Sanskrit) and different endings convey different meanings. Many verb endings in Japanese, which you can see in Hyakunin Isshu poetry, no longer exist, or are replaced with other endings. Let’s look at a concrete example.

Poem 73 (たか) is a nice example of things that changed, and things that have remained the same.

| Japanese | Romanization | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| 高砂の | Takasago no | Above the lower slopes |

| 尾のへの桜 | Onoe no sakura | of the high mountains, the cherries |

| 咲きにけり | Saki ni keri | have blossomed! |

| とやまのかすみ | Toyama no kasumi | O, mist of the near mountains, |

| 立たずもあらなむ | Tatazu mo aranan | how I wish you would not rise! |

Some words like sakura (cherry blossoms) and kasumi (mists) haven’t changed at all. The possessive particle no meaning “of, or belonging to” hasn’t changed either in terms of usage.1

On other other hand, we see some grammar not found in modern Japanese. For example, in old Japanese, especially poetry a verb-stem ending with ni keri meant that something has been done (from past to present). Modern Japanese uses verb endings like te kita, te itta, and so on to convey similar context.

Another example is –zu mo aranan, which I wasn’t able to find online, but based on verb tatsu (to rise, to stand), obviously means implies a negative connotation (i.e. not do something). In modern Japanese you can say something similar: tatazu ni (without standing…), so again you can see the continuity.

Something you often see, but not shown in this poem is adjective endings. Modern Japanese adjectives often end with an i sound, for example “cold” is samui, “fast” is hayai, and so on. But in old Japanese the i was often a ki: samuki, hayaki, and so on. I noticed both in the Hyakunin Isshu, but also in Japanese RPG games when they take place in old “fantasy times”, because it helps convey a sense of ages past.

Finally, some words just change meaning over time. I was surprised to learn that the word for “shadow” kagé used to mean “light”, as in tsuki-kagé (moonlight). So, even if the word stays the same, the nuance does evolve over time.

Finding information on Early Middle Japanese in English is pretty difficult, and often requires an academic background. Since I am just an amateur hobbyist, this is only a brief overview. There is a lot more to cover, but hopefully gives you a brief sense of how things have changed over time. Japanese is a language that shows a nice continuum over its long history, and it’s fascinating to see howd the same language looked and sounded so far back.

1 I think I read somewhere that in really, really old Japanese the “no” possessive particle used to be “na”. I don’t know if that relates somehow to the “na-adjectives” in Japanese language, but I do wonder.