In the Hyakunin Isshu poetry anthology, the subject of this blog for almost 15 years (!), there are many poems about love, nature, sadness, etc. But none about death. There are poems on betrayal, but in the context of infidelity, not on stabbing others in the back.

…. and yet, beneath the surface there are other stories to be told.

In the seventh century, with the death of Emperor Kōtoku in 654 CE, another power struggle erupted. One one side was the emperor’s son, Prince Arima (有間皇子, 640-658), and on the other was the emperor’s older sister and reigning sovereign Emperess Saimei. Empress Saimei had her own son named Prince Naka-no-ōe (中大兄皇子) and was a rival to Prince Arima, Because his mother was the reigning sovereign, Naka-no-ōe would be next in line for the throne, not cousin Prince Arima who was left in the cold.

According to historical accounts, Arima was quietly approached by one Soga no Akae (蘇我赤兄), grandson of the influential Soga no Umako, who promised to help him overthrow Empress Saimei and support his ascension to the throne. Initially, Arima was interested, but later got cold feet. He swore Soga no Akae not to tell anyone, and to call the whole thing off.

But what Arima didn’t know, was that the whole thing was a setup. Prince Naka-no-ōe had planned the whole thing, and Akae told him what happened.

Prince Arima was soon arrested, and taken outside the capitol for interrogation. On his way there, at a place called Iwashiro no Hama (“Iwashiro Beach”),1 he tied a cord, or a piece of grass to a pine branch. This was evidentially a tradition at the time to pray for good luck on one’s journeys.

Once the interrogations were complete, Prince Arima was sent back toward the capital, but was executed en route by hanging at a place called Muro no Yu (牟婁の湯), which is now a seaside resort town. He was 19 at the time, the year was 658 CE.

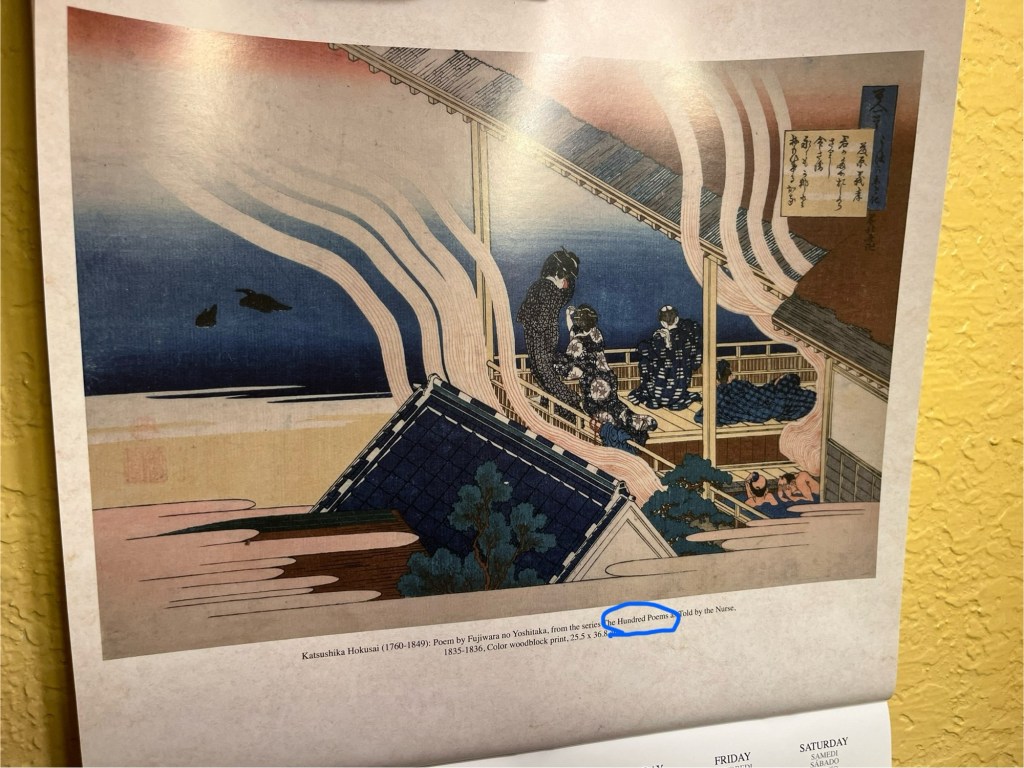

Forty-three years later (701 CE), Kakinomoto Hitomaro (poem 3 in the Hyakunin Isshu, あし) was serving the current Emperor Monmu, grandson of Empress Jito (poem 2, はるす), and during an an imperial outing they came to Muro no Yu. By now, Prince Arima’s demise was well-known, including the story of him tying cord to a pine tree branch. Hitomaro, remembering what happened, composed the following poem (poem 146 in the Manyoshu):

| Original Manyogana | Modern Japanese | Romanization | Rough translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 後将見跡 | 後見むと | Nochi mimu to | That pine branch that |

| 君之結有 | 君が結べる | Kimi ga musuberu | you were going to visit |

| 磐代乃 | 磐代の | Iwashiro no | after tying a cord: |

| 子松之宇礼乎 | 小松がうれを | Komatsu ga ure wo | I wonder if you ever did |

| 又将見香聞 | またも見むかも | Mata mo mimu kamo | see it again… |

Kakinomoto Hitomaro is reminiscing whether Prince Arima got to see the pine branch again one his way back, before he was executed. It’s a sad poem on the tragically short-lived prince.

But there’s more to the story.

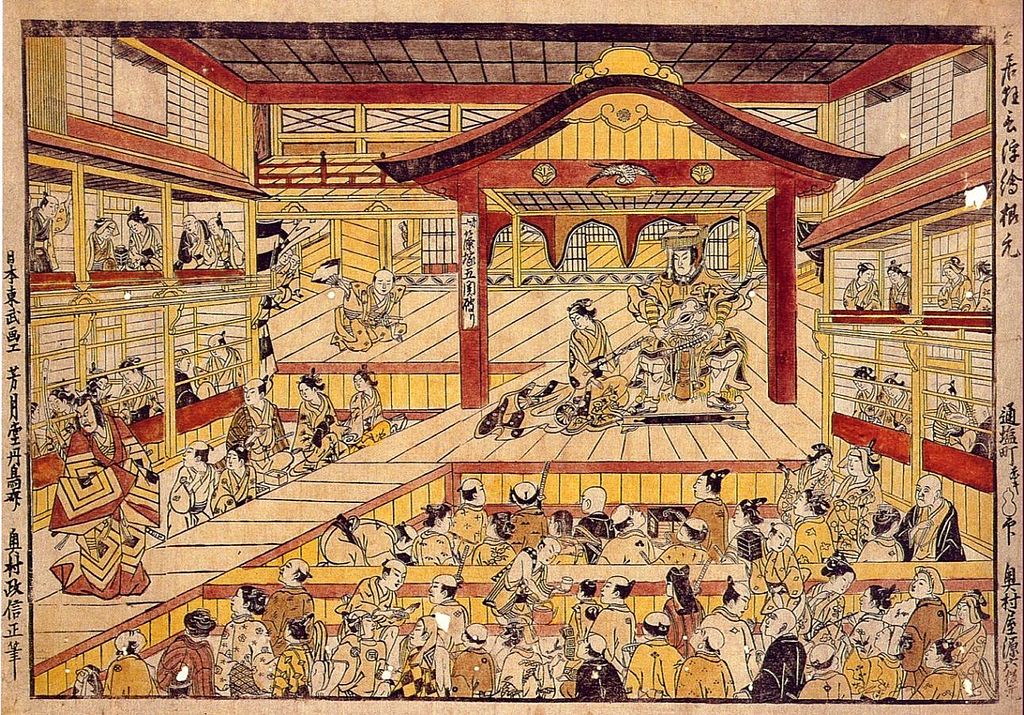

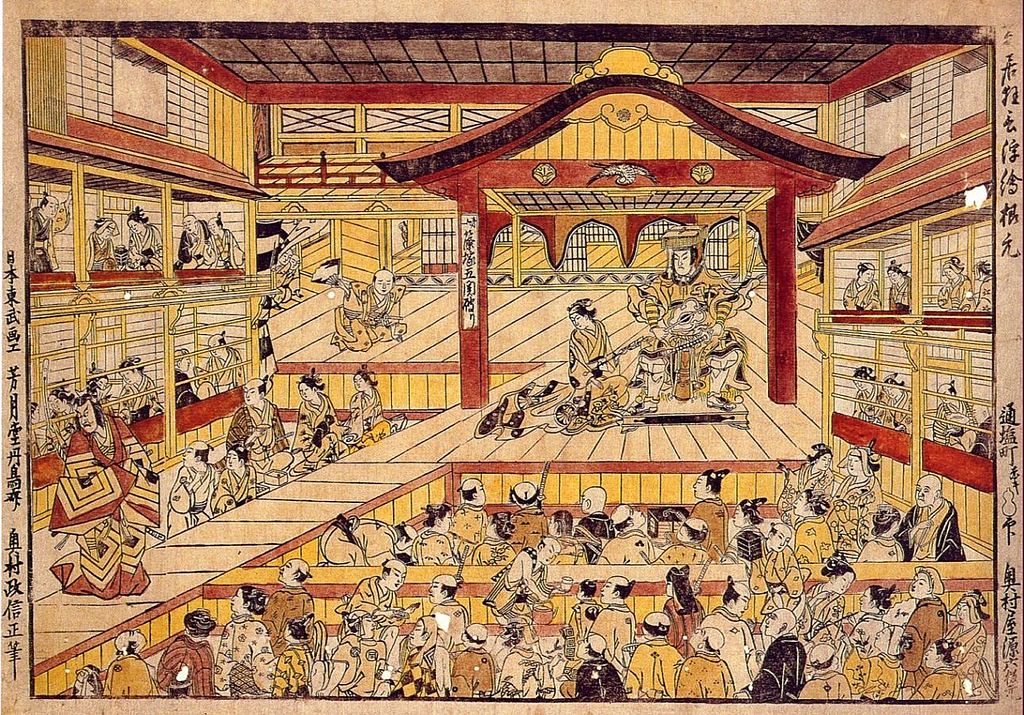

Soga no Akae and his clan, the Soga were frequent troublemakers at this time, and both Empress Saimei and her son Prince Naka-no-ōe executed or assassinated multiple members of the clan at the instigation of the Nakatomi. The Nakatomi were later renamed “Fujiwara”, and if you look at the list of poems in the Hyakunin Isshu, you see a lot Fujiwara poets. There’s a very good reason for this. The final straw for the Soga Clan was in 672 when yet another power struggle put the Soga on the losing side of the war. Akae was among those exiled. The Soga permanently lost power.

And finally: what happened to the powerful and conniving Prince Naka-no-ōe?

He eventually ascended the throne as Emperor Tenji, poem 1 of the Hyakunin Isshu (あきの) and instigator of conflicts of his own.

So, it’s interesting to read his poem in the Hyakunin Isshu and its rosy picture of a fall harvest, knowing that the man had some blood on his hands too…

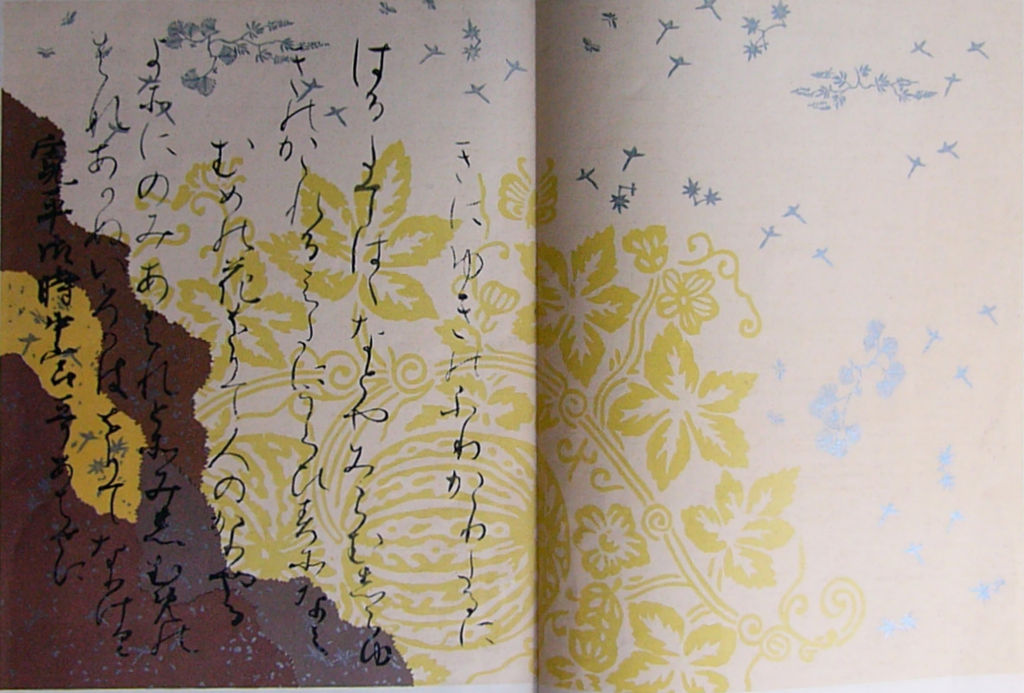

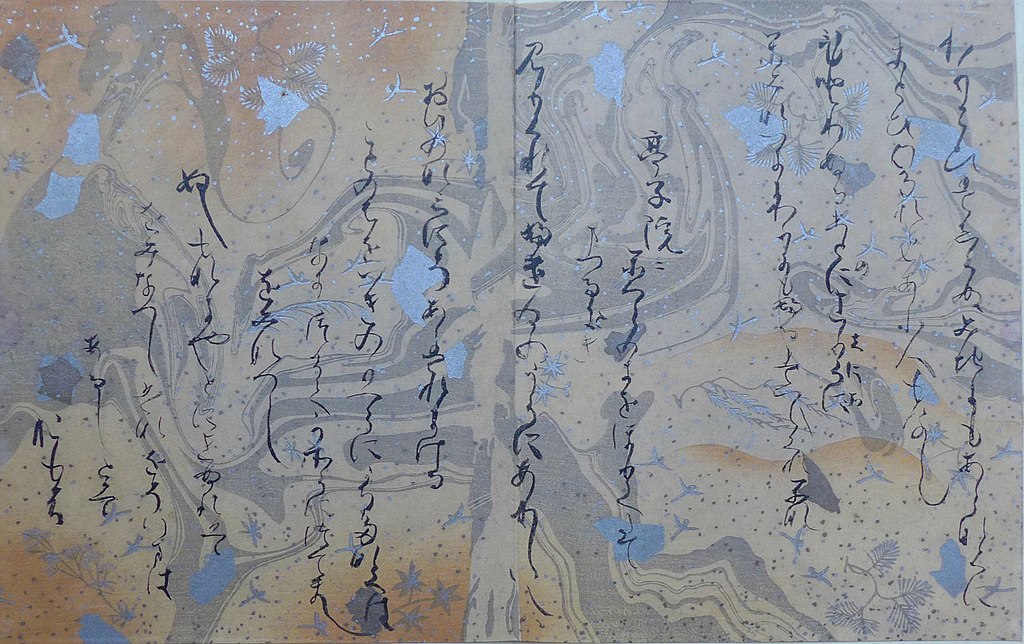

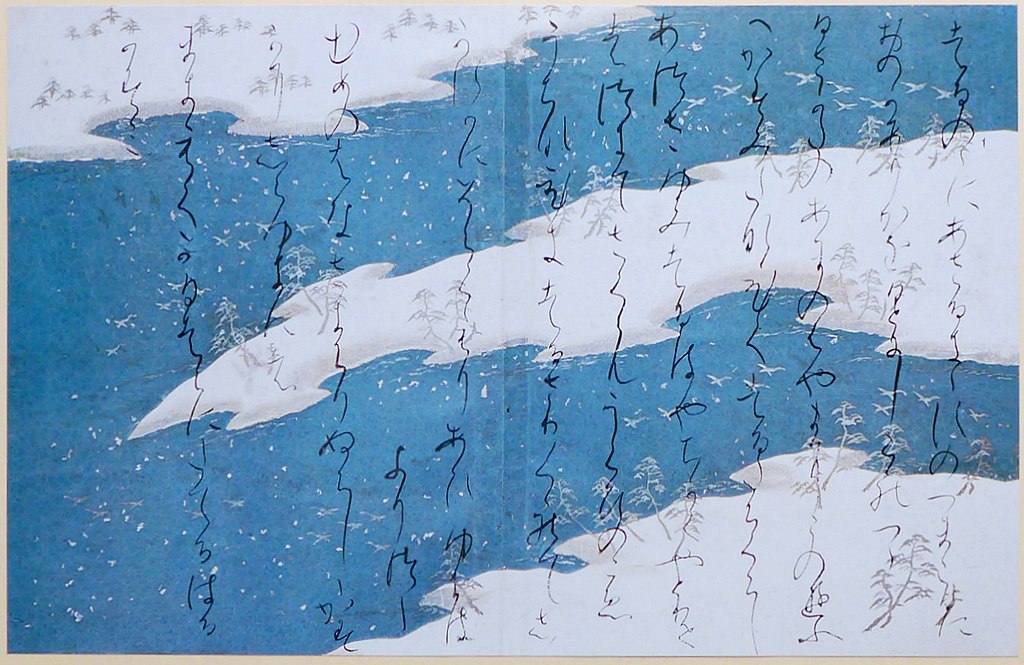

P.S. featured photo is a 17th century depiction of the power struggle between Empress Saimei and the Soga Clan. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

P.P.S. another post on the dark political history behind some poets of the Hyakunin Isshu.

1 You can see modern photos of the place here. It is in Wakayama Prefecture.