The fashion of the nobility of the Heian Period of Japanese history is fairly different than later, more familiar styles we often see in Japanese media like anime, manga, etc., because it reflects early Chinese influence, but also increasingly local innovations and culture. Further, as we’ll see, because the aristocracy was socially rigid and had many complex customs and rules, this affected how people dressed as well. Everyone knew their place, and their fashion reflected this too. I have touched on the subject a little bit here and here, but I always wanted to explore in depth. The issue was (until recently) a lack of resources and time. But, here we go.

Some great online resources for fashion during the Heian Period of Japanese history (c. 8th century to 12th century) can be found on this website (Google translated version here), and this site. The second link has some English in it, so even if you can’t read Japanese, it’s a great place to visit and look around.

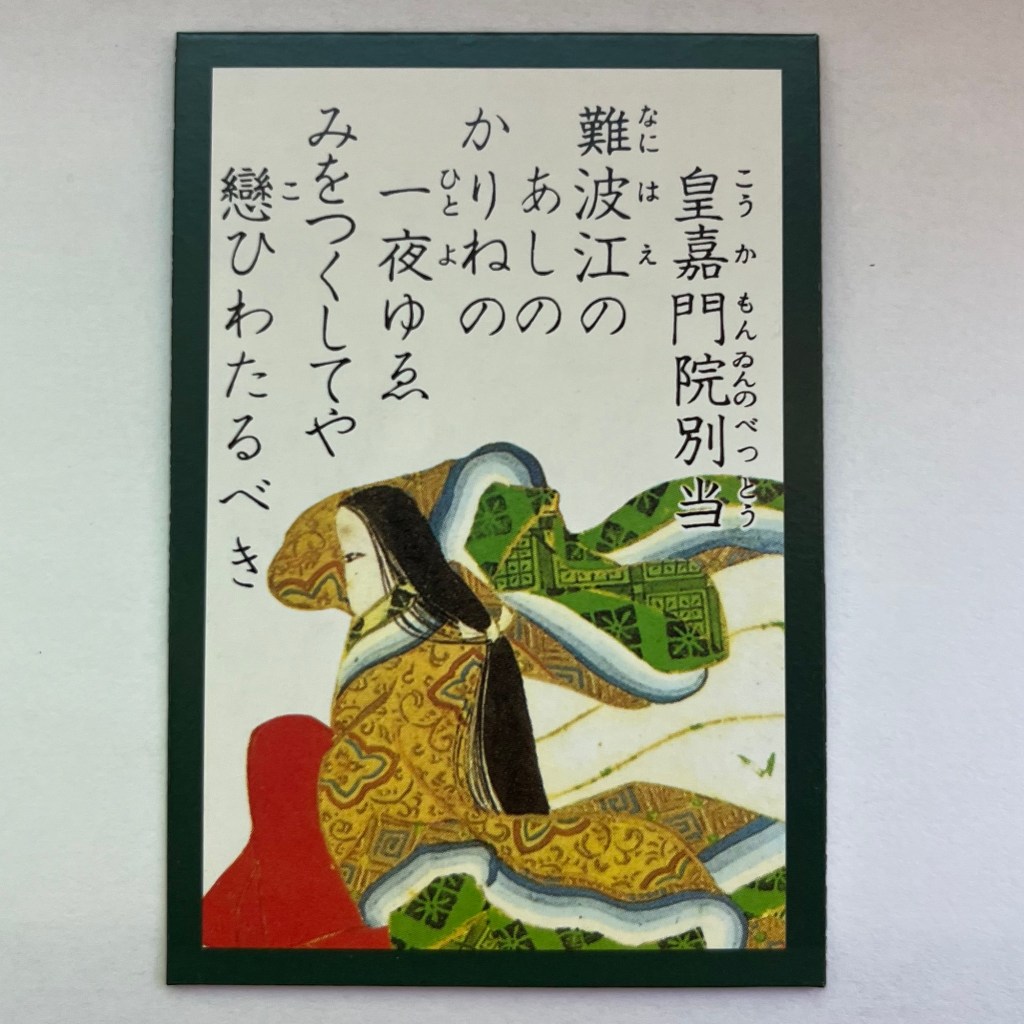

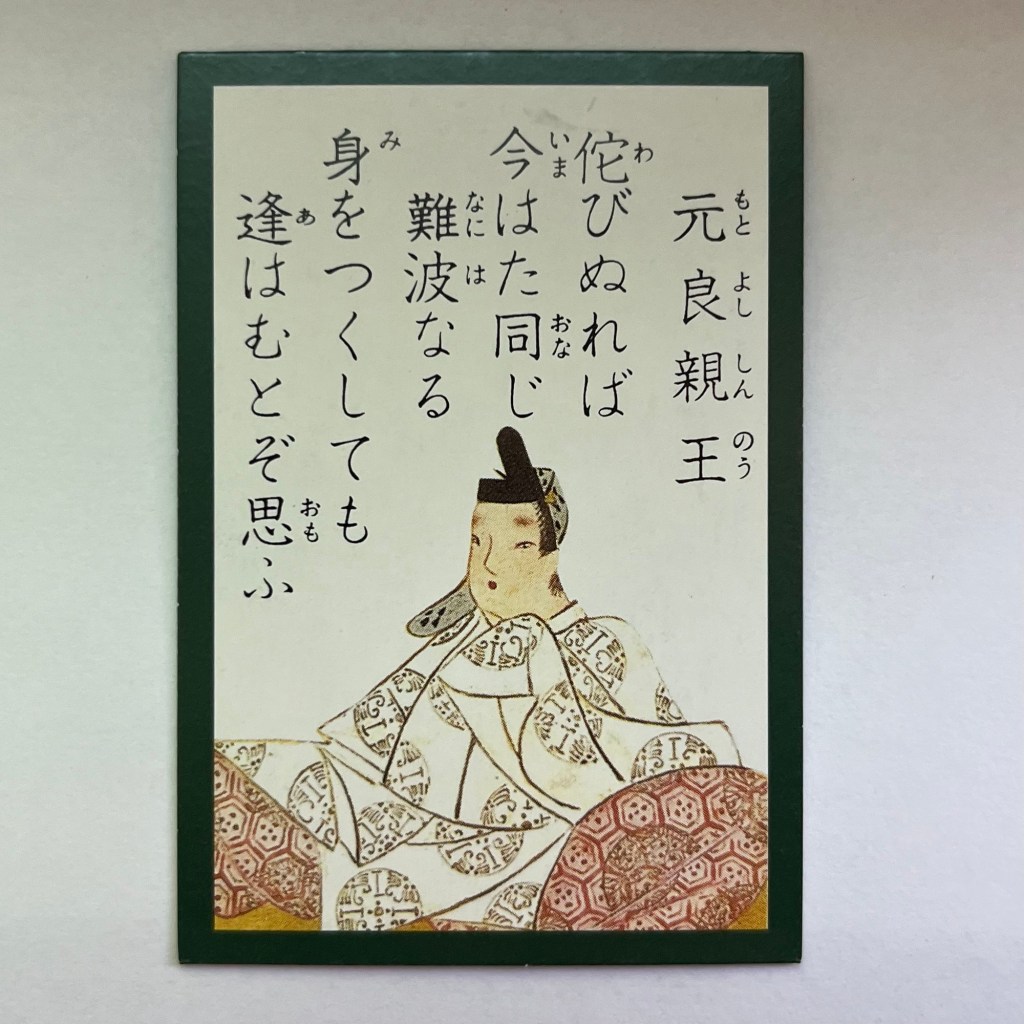

However, for us Hyakunin Isshu poetry (and karuta) fans, you can see many great examples in the yomifuda cards too.

Women’s Fashion

This card, depicts Daini no Sanmi (poem 58, ありま) of the Hyakunin Isshu. The illustration, part of the Ogata Korin collection, shows her in full formal dress.

Like many women of the Heian Period, during formal occasions, she would wear multiple layers of kimono robes called junihito-é (十二単) which literally translates to “twelve robes”. The women of the court did not actually wear 12 layers, but it was much heavier and bulkier than kimono fashion of later centuries.

Here’s another example: Suō no Naishi (poem 67, はるの):

And another: Kōkamonin no Bettō (poem 88, なにはえ):

A few things worth pointing out…

- The robes (hitoé, 単) were very long and thus hard to walk in.

- Over the layers of robes, the women would wear a “Chinese jacket” (karaginu, 唐衣).

- The white train in the back was called a mo (裳), which tied around the waist.

- The women wore hakama (袴) trousers much like Japanese traditional clothing today.

You can see a really good example of this kind of fashion here. Definitely check out the link.

Men’s Fashion

Men’s formal wear, if you can believe it, was actually more complicated than women’s. Broadly speaking, it could be divided into three categories: civil bureaucrats, warriors (e.g. palace guards), and upper class nobility including the Emperor.

Imperial Advisors

Because the Imperial court of Japan was modeled after the Chinese-Confucian bureaucracy from antiquity, there are some similarities in the fashion of the civil servants (bunkan, 文官): black robes, similar hats, etc. We can see some examples here: Middle Counselor Yakamochi (poem 6, かさ):

and Middle Counselor Yukihira (poem 16, たち):

Some things to point out here:

- The hat they wore, the sui-ei-kan (垂纓冠) was a black lacquer helmet, but in this case, also had a ribbon hanging down the back too.

- Black silk overcoat called a ho (枹), based on Chinese-Confucian style.

- The high collar in the back was called an agekubi (盤領)

- In formal settings, men would also wield a small, flat wooden scepter called a shaku (笏).

- The silk pants were a variation of the modern Japanese hakama called an ué-no-hakama (表袴).

- Finally, the shoes were a kind of black lacquer clogs called asagutsu (浅沓). Similarly to the women’s formal wear, it was hard to walk in.

You can see some great examples of both the summer dress and the winter dress.

One thing to note is that even samurai warlords who ruled the country in later periods (see Sanetomo), when they came to the capital (jōraku 上洛) were expected to wear this kind of court dress befitting whatever rank they had been bestowed. Although the samurai class held true power, they were still technically part of the Imperial court so customs persisted.

Guards

For the palace guards and other military figures, the formal dress was similar to the bureaucrats above, but with some notable differences. A good example from the Hyakunin Isshu is Fujiwara no Michinobu (poem 52, あけ):

Noting the differences here:

- Guards and military figures were equipped with a sword (ken, 剣), bow (yumi, 弓), and a quiver of arrows (ya, 矢).

- The crown on their head was shaped in a loop, not a long trailing one. It was called a ken-ei-kan (巻纓冠) instead.

- The crown also had two fan-like protrusions called oikake (緌).

- Instead of black-lacquer clogs, the shoes were often pointed-toe boots called kanokutsu (靴).

You can see an example here.

Upper Nobility

The upper nobility wore clothing that was pretty similar to other members court, but with one major exception: the colors of their robes. Here you can see Prince Motoyoshi (poem 20, わび):

As eluded to in Lady Murasaki’s diary and other sources, there was a strict hierarchy within the Court nobility, which was reinforced by which colors of robes people were permitted to wear. This included colors such as green (shown here), orange (shown here) or white (shown here). The green linked above was, for example, permitted to courtiers of the sixth rank, or palace servants of the fourth rank. Wikipedia has list of forbidden colors, and what ranks were associated with each. The point is is that just by looking at someone’s robes, members of the aristocracy knew each other’s place.

The very upper class nobility, namely those of the Emperor and his family, are often depicted in white robes with red trimming, which is similar to those used by Shinto priests (shown here). It’s probable this was intended to reinforce the Imperial family’s divine lineage, but that’s just a guess on my part.

The fashion used in the yomifuda Karuta cards really tells us a lot about the culture that the poets of the Hyakunin Isshu lived in.