As fall is approaching, I wanted to share an interesting anecdote provided by my book on the Manyoshu. It seems that throughout Japanese antiquity, poets frequently debated which is better: spring or fall.

The first example comes from Princess Nukata in the 7th century, whom we discussed here and here, she wrote a lengthy poem (a chōka poem, not the usual tanka poem) in the Manyoshu (poem 16). She discusses the pros and cons of spring and of fall:

| Original Manyogana1 | Japanese | Romanization | Rough Translation2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 冬木成 春去來者 | 冬ごもり 春さり來れば | Fuyu gomori haru sari kureba | When winter passes and spring comes |

| 不喧有之 鳥毛来鳴奴 | 鳴かざりし鳥も來鳴きぬ | Nakazarishi tori mo nakinu | Birds that didn’t sing before, now come and sing |

| 不開有之 花毛佐家礼抒 山乎茂 | 咲かざりし 花も咲けれど 山を茂み | Sakazarishi hana mo sakeredo yama wo shigemi | Flowers that didn’t bloom before now bloom, but because the mountains grass is so thick |

| 入而毛不取 草深 執手母不見 | 入りても取らず 草深み 取り手も見ず | Irite mo torazu kusabukami torite me mizu | One cannot go and pick flowers, let alone see them. |

| 秋山乃 木葉乎見而者 | 秋山の 木の葉を見ては | Aki yama no ko no ba wo mite wa | When you look at the leaves in the mountains during fall, |

| 黄葉乎婆 取而曾思努布 | 黄葉をば 取りてそしのふ | Momiji wo ba torite soshi no fu | collecting the yellow leaves is especially prized. |

| 青乎者 置而曾歎久 | 青きをば 置きてそ歎く | Aoki wo ba okite so nageku | Leaving the green leaves as they are is regrettable. |

| 曾許之恨之 秋山吾者 | そこし恨めし 秋山われは | Sokoshi urameshi akiyama ware wa | In spite of that, autumn in the mountains is spectacular… |

Speaking of the Manyoshu, its compiler Otomo no Yakamochi (poem 6 of the Hyakunin Isshu, かさ) left us some very nice poetry about spring:

| Original Manyogana1 | Japanese | Romanization | Rough Translation2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 春苑 | 春の苑 | Haru no sono | Beneath |

| 紅尓保布 | 紅にほふ | Kurenai ni hofu | the shining crimson |

| 桃花 | 桃の花 | Momo no hana | orchard of |

| 下照道尓 | 下照る道に | Shita deru michi ni | peach blossoms |

| 出立オ嬬 | 出で立つ少女 | Idetatsu otome | a young maiden lingers. |

and about fall:

| Original Manyogana1 | Japanese | Romanization | Rough Translation2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 秋去者 | 秋さらば | Aki saraba | When fall comes |

| 見乍思跡 | 見つつ思へと | Mitsutsu shinoe to | think fondly of those |

| 妹之殖之 | 妹が植ゑし | Imo ga ue shi | pink blossoms |

| 屋前乃石竹 | やどのなでしこ | Yado no nadeshiko | of days gone by |

| 開家流香聞 | 咲きにけるかも | Saki ni keru kamo | and remember me. |

Otomo no Yakamochi wrote both of these poems about his beloved wife, but the second was composed shortly after her parting. The word nadeshiko has special meaning in Japan and has a very feminine, demure3 meaning.

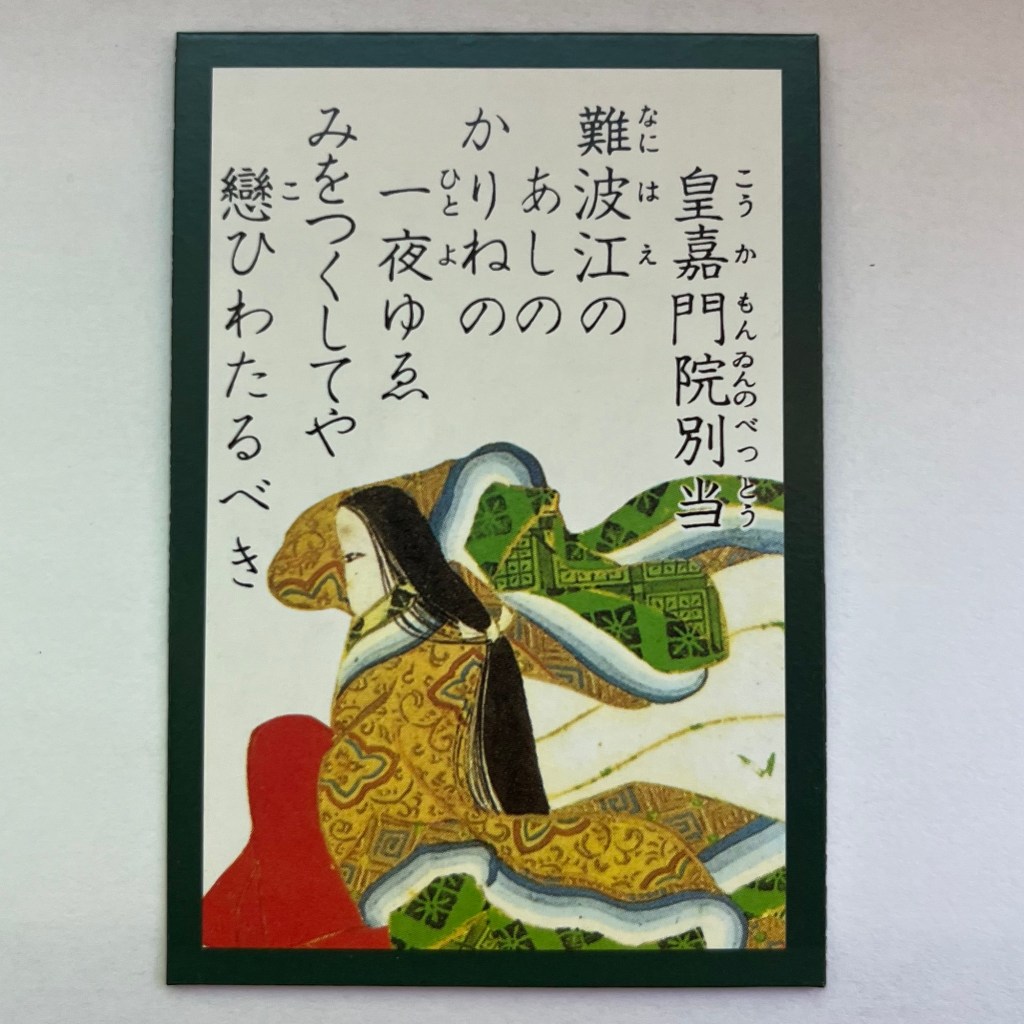

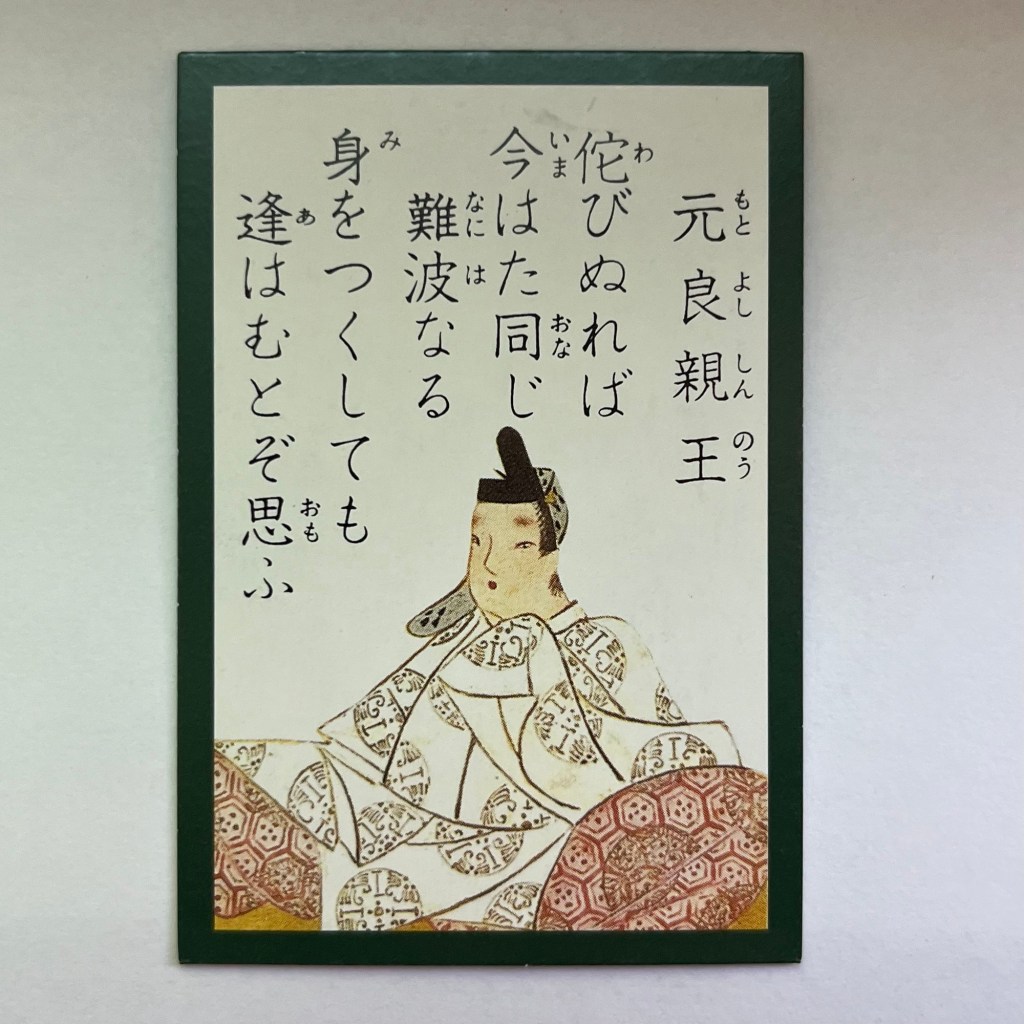

Returning to the debate between spring and fall, Ki no Tsurayuki (poem 35 of the Hyakunin Isshu, ひとは) took up the same topic centuries later. This is poem 509 from an imperial anthology, the Shuishu :

| Japanese | Romanization | Rough Translation2 |

|---|---|---|

| 春秋に | Haru aki ni | Spring or Fall? |

| おもひみたれて | Omoi mitarete | My thoughts are a mess, |

| わきかねつ | Waki kanetsu | and I cannot decide. |

| 時につけつつ | Toki ni tsuketsutsu | The more time passes, |

| うつるこころは | Utsuru kokoro wa | the more my heart shifts back and forth. |

The debate was even cited in the famous 12th century novel Tales of Genji written by Lady Murasaki (poem 57 of the Hyakunin Isshu, め):

春秋の争ひに、昔より秋に心寄する人は数まさりけるを、名立たる春の御前の花園に心寄せし人びと、また引きかへし移ろふけしき、世のありさまに似たり。

“Since antiquity, in the debate about spring versus fall, many people lean toward fall, and yet some very noteworthy people who view the Imperial gardens in spring may yet change their mind, as is the way of the world.”

Princess Nukata all the way back in the Manyoshu seemed to imply that autumn was preferable, and it seems that most of the aristocracy shared this view. In fact if we divide up the poems of the Hyakunin Isshu by season, there are more fall poems than spring:

| Spring Poems, first verse listed | Fall Poems, first verse listed |

|---|---|

| Hana no iro (poem 9) Kimi ga tame haru (poem 15) Hito wa isa (poem 35) Inishie no (poem 61) Morotomo ni (poem 66) Haru no yo no (poem 67) Takasago no (poem 73) Hana sasou (poem 96) | Aki no ta no (poem 1) Ashibiki no (poem 3) Okuyama ni (poem 5) Waga io wa (poem 8) Chihayaburu (poem 17) Ima kon to (poem 21) Fuku kara ni (poem 22) Tsuki mireba (poem 23) Kono tabi wa (poem 24) Ogurayama (poem 26) Kokoroate ni (poem 29) Yamagawa ni (poem 32) Shiratsuyu wo (poem 37) Yaemugura (poem 47) Arashi fuku (poem 69) Sabishisa ni (poem 70) Yū sareba (poem 71) Akikaze ni (poem 79) Yo no naka yo (poem 83) Nageke tote (poem 86) Murasame no (poem 87) Kirigirisu (poem 91) Miyoshino no (poem 94) |

But what do you think? Are you Team Spring, or Team Fall?

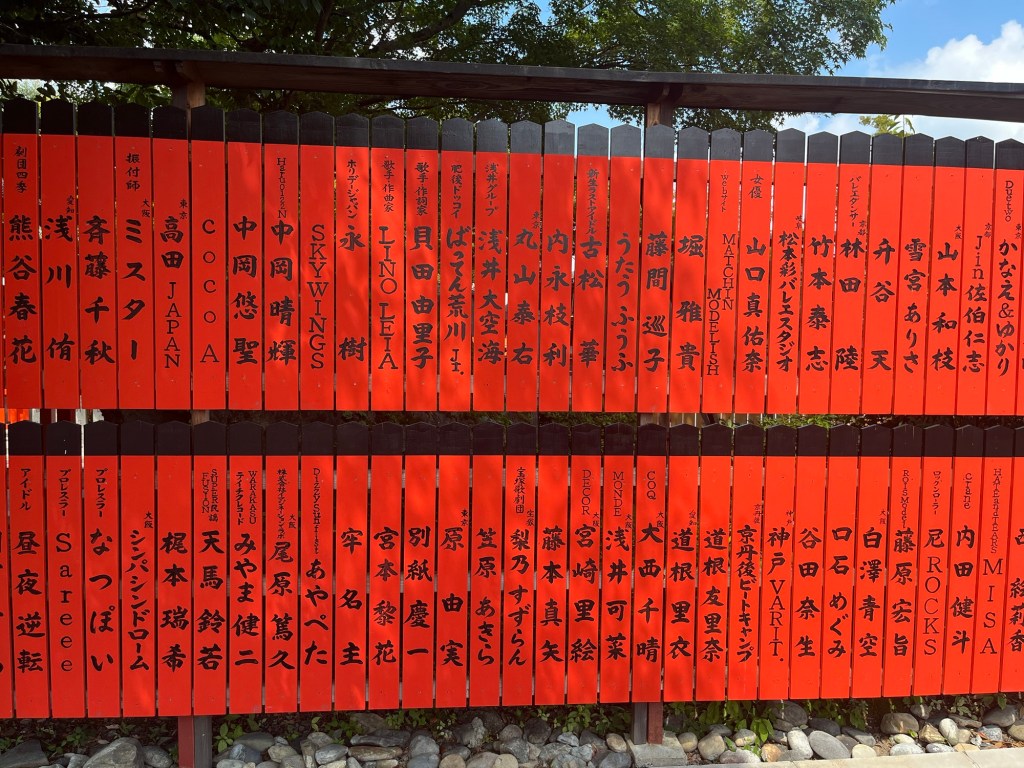

Edit: added Hyakunin Isshu poetry chart.

1 If you’re wondering why I post Manyogana for some poems, but not others, it depends on the era. The Manyoshu is the oldest anthology by far, and at that time, there was a brief writing system that took Chinese characters, but used them in a phonetic way for Japanese language (a.k.a. Manyogana). By the time of Ki no Tsurayuki and Lady Murasaki, centuries later, this had been replaced with hiragana script. This blog strives to both be accurate and accessible, so I try to balance both needs.

2 These are all rough translations on my part, and likely have mistakes. Any such mistakes are entirely my own.

3 Not to be confused with the “very demure, very mindful” meme. 😛