One of my biggest challenges with learning to play karuta are penalties (otetsuki, お手付き). A penalty happens in one of there scenarios:

- The correct card is on the opponents side, but you touch a card on your side for any reason.

- The correct card is on your side, but for any reason you touch a card on the opponent’s side.

- The card is not on the board (karafuda, から札), but for any reason you touch a card on the board.

In all three cases the result is the same: your opponent is allowed to send a card over to you. Their card count is reduced by one (advantage), and your card count also increases by one (disadvantage).

If you think about it, a penalty is more costly than simply letting your opponent take the card. In the rare case of a double penalty, it is extremely costly because your opponent will send over two cards.

However, the pressure to correctly identify and then take the correct card before your opponent makes penalties possible, even for pro players. However, the more you prevent penalties the better your gameplay overall.

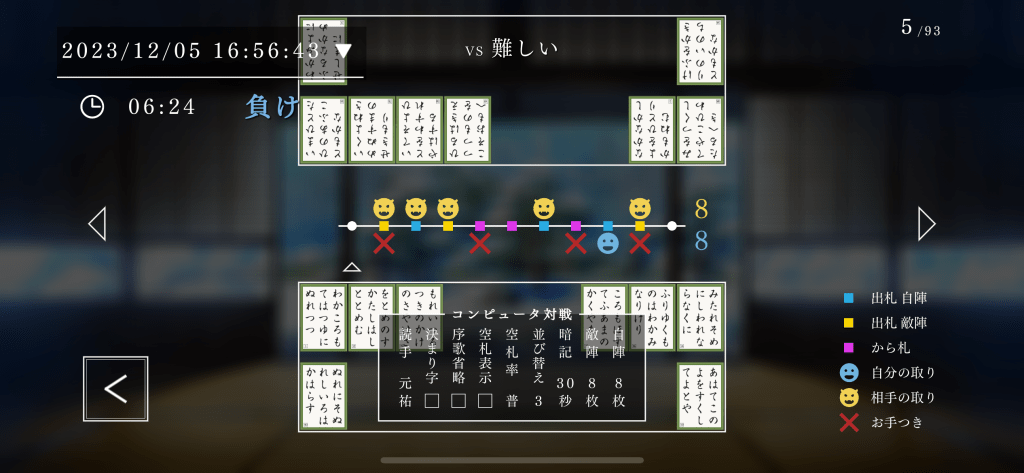

In my case, I get penalties often under pressure. In some games, I get as many as 8-9 penalties which is disastrous. The featured photo is a game I lost recently where I had 6 penalties. I would have still lost but the margin was much bigger due to penalties and panic (i.e. “tilting”).

If I calm down and focus, I can reduce this far fewer. Sometimes when I panic, I have to remind myself that it is better to be slow, than to be wrong.

For the past month, I have been striving to reduce my penalty rate and found a great article in Japanese. It identifies a few different patterns of penalties people tend to do, and how to counteract each. I won’t explain the article word for word, but some of the more common patterns are:

- Forgetting (or mis-remembering) the position of cards on the board. This requires a grasp of the kimariji for quick recognition, and focus to maintain a “mental map” in your head. Personally, I find it helpful to focus on an empty spot on the board as a meditation “focal point”, so I can visualize without looking.

- Hitting cards on both sides of the board on accident. This requires physically practicing how you move your hand and being quick, but more precise.

- Listening incorrectly (or jumping the gun) and taking the wrong card. This is very common and a good habit to break quickly.

One method I have used and wrote about before is playing solo and reducing the pressure while focusing on being correct, not fast.

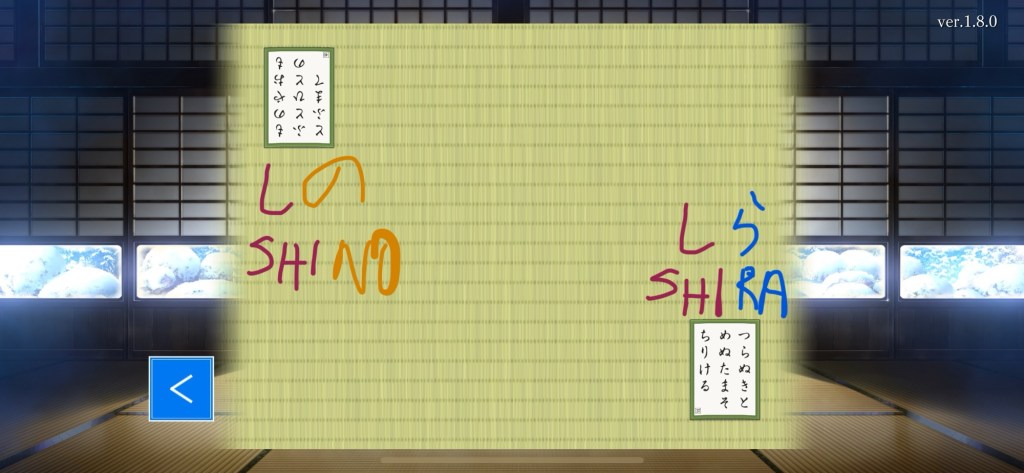

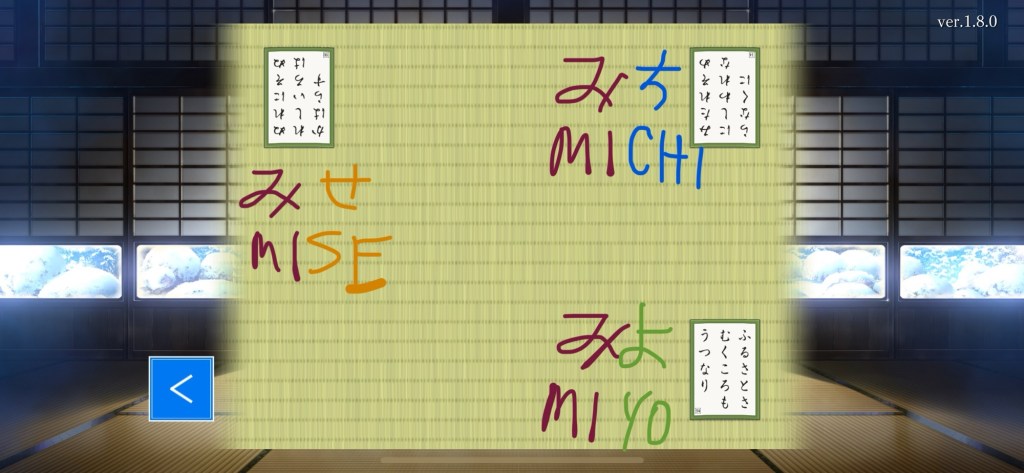

Another, general method for reducing penalties is practicing kikiwaké (聞き分け): “separating sounds”. This is a form of teaming and a mini-game in the online karuta app called “Branching Cards” in English. The Japanese kikiwake means to listen and differentiate.

In each round you will be presented with 2-3 tomofuda (友札), or cards with similar kimariji. Your job is to listen and take the correct one. There are no empty cards; the correct one is always on the board somewhere.

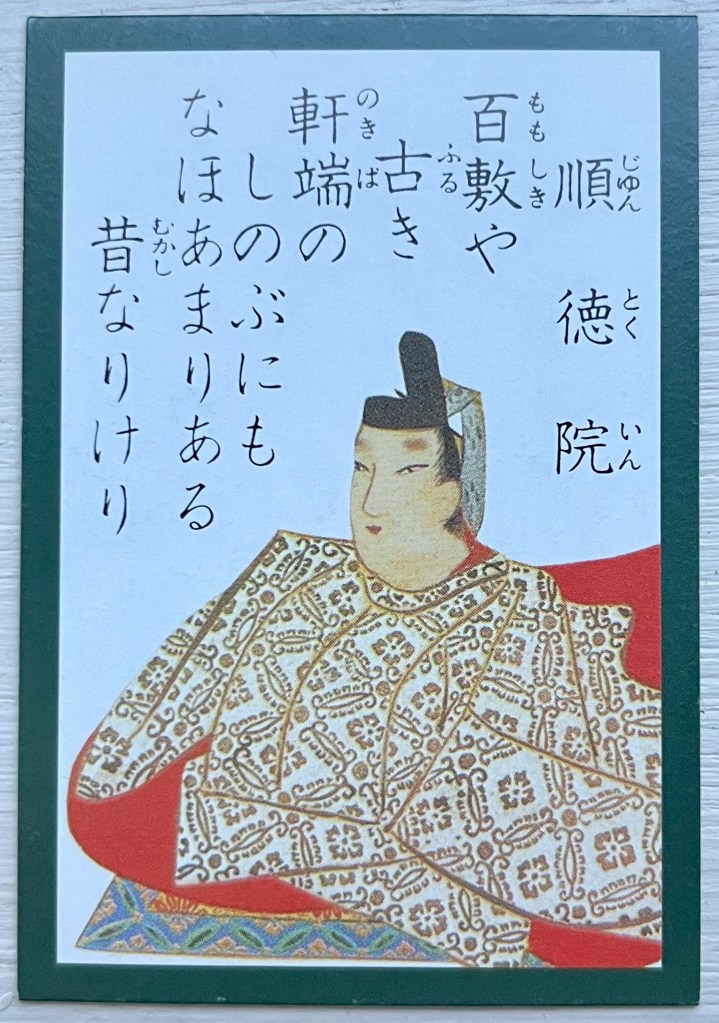

As the article explains above, you should focus on the last syllable of each kimariji so that you can more easily differentiate which is being read.

In the example below, there are two cards with kimariji of しの (shino) and しら (shira). The の and ら are what differentiate the two.

In a more challenging example, there are cards with kimariji of みせ (mise), みち (michi) and みよ (miyo). The せ, ち, and よ are what differentiate the three.

At first this is surprisingly tough to do. You have to recognize the cards quickly, and then listen for the important syllable. I made many mistakes at first, but after a couple weeks, I’ve gotten better about waiting until the correct syllable is read.

As always keep practicing fudawake, but also strive to improve your listening and self-discipline too.

Good luck!