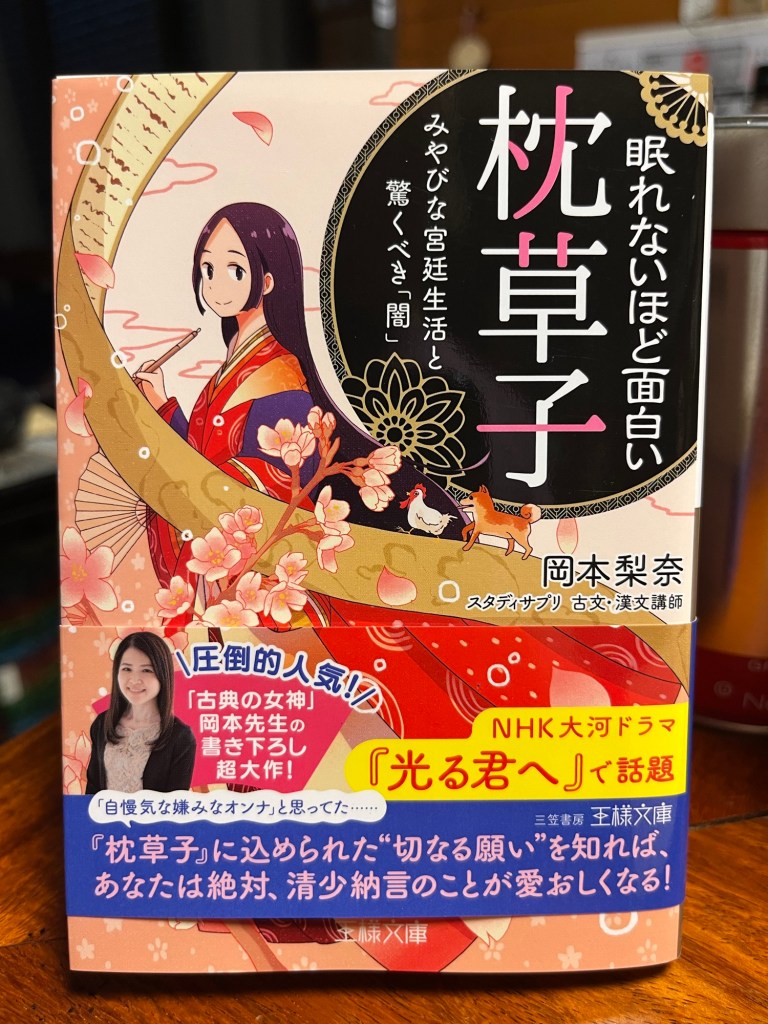

Ever since I picked up this book which explores the Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon (poem 62 of the Hyakunin Isshu, よを), it’s been fun to learn many of the hidden meanings and cultural allusions of this famous literary work.

It’s also fun to see how the Pillow Book is viewed by Japanese students in Japan. I talked with my wife and her friends about it, and they confirmed that kids in Japan study the Pillow Book in school, but like all students everywhere, they tend to forget most of it.1 My book jokes that most students in Japan only remember the very first line: haru wa akebono.

I bring this up because with the recent changing of the weather, I’ve been thinking a lot about seasons, especially after writing this post. So, I went back and looked at the first chapter of the Pillow Book.

The opening section begins with Sei Shonagon’s analysis of the four seasons, and what’s great about each one. This website posts the original text in Japanese (tl;dr it’s fairly different than modern Japanese) and even has a nice recording. It’s worth a listen, even if archaic Japanese is not your hobby.

Separately, if you want to hear how it was pronounced at the time you can see this video (00:47 onward):

Anyhow, let’s look at how Sei Shonagon describes each of the four seasons, starting with Spring…

Spring

As alluded to earlier, Sei Shonagon opens her book with the following passage about Spring:

春は、あけぼの。やうやうしろくなりゆく山ぎは、すこし明かりて、紫だちたる雲の、細くたなびきたる。

Haru wa akebono. Yoyoshiroku nariyuku yamagi wa, sukoshi akarite, murasaki dachitaru kumo no hosoku tanabikitaru.

“In spring, the dawn — when the slowing paling mountain rim is tinged with red, and wisps of faintly crimson purple cloud float in the sky.”

Translation by Dr. Meredith McKinney

Summer

and of Summer:

夏は、夜。月のころはさらなり。闇もなほ、蛍の多く飛びちがひたる。また、ただ一つ二つなど、ほのかにうち光りて行くも、をかし。雨など降るも、をかし。

Natsu wa yoru. Tsuki no koro wa sarinari. Yami mo nao, hotaru no ooku tobichigaitaru. Mata, tada hitsotsu futatsu nado, honoka ni uchi hikarite iku mo, okashi. Ame nado furu mo, okashi.

“In summer, the night — moonlight nights, of course, but also as the dark of the moon, it’s beautiful when fireflies are dancing everywhere in a mazy flight. And it’s delightful too to see just one or two fly through the darkness, glowing softly. Rain falling on a summer night is also lovely.”

Translation by Dr. Meredith McKinney

Autumn

Of Autumn, she writes:

秋は、夕暮。夕日のさして、山の端いと近うなりたるに、烏の寝どころへ行くとて、三つ四つ、二つ三つなど、飛びいそぐさへあはれなり。まいて、雁などのつらねたるが、いと小さく見ゆるは、いとをかし。日入りはてて、風の音、虫の音など、はた、言ふべきにあらず。

Aki wa yuugure. Yuuhi no sashite, yama no hai to chikau nari taru ni, karasu no nedokoro e ikutote, mitsu, yotsu, futatsu mitsu nado, tobiisogu sae awarenari. Maite, kari nado no tsuranetaru ga, ito chiisaku miyuru wa, itokashi. Hiirihatete, kaze no oto, mushi no ne nado, hata, iiubeki ni arazu.

“In autumn, the evening — the blazing sun has sunk very close to the mountain rim, and now even the crows, in threes and fours or twos and threes, hurrying to their roost, are a moving sight. Still more enchanting is the sight of a string of wild geese in the distant sky, very tiny. And oh how inexpressible, when the sun has sunk, to hear in the growing darkness the wind, and the song of autumn insects.”

Translation by Dr. Meredith McKinney

Winter

and finally Winter:

冬は、つとめて。雪の降りたるは、言ふべきにもあらず。霜のいと白きも。またさらでも、いと寒きに、火など急ぎおこして、炭持てわたるも、いとつきづきし。昼になりて、ぬるくゆるびもていけば、火桶の火も、白き灰がちになりて、わろし。

Fuyu wa tsutomete. Yuki no furitaru wa, iubeki ni mo arazu. Shimo no ito shiroki mo. Mata sara demo, itso samuki ni, hi nado isogi okoshite, sumi motewataru mo, ito tsukizuki shi. Hiru ni narite, nurukuyurubi moteikeba, hioke no hi mo, shiroki hai ga chininarite, waroshi.

“In winter, the early morning — if snow is falling, of course, it’s unutterably delightful, but it’s perfect too if there’s a pure white frost, or even just when it’s very cold, and they hasten to build up the fires in the braziers and carry fresh charcoal. But it’s unpleasant, as the day draws on and the air grows warmer, how the brazier fire dies down to white ash.”

Translation by Dr. Meredith McKinney

As someone who likes to “nerd out” about such things, I try to shorten this to the following for easier memorization:

- Spring: haru wa akebono (spring daybreak)

- Summer: natsu wa yoru (summer nights)

- Fall: aki wa yuugure (fall sunsets)

- Winter: huyu wa tsutomete (early winter morning)

… and now you too know some authentic Japanese literature from the Heian Period.

1 Despite being a nerd now, I was actually a pretty lazy student in school. I was assigned to read various English classics like Ivanhoe, Treasure Island, etc, but usually didn’t read them, and faked my way through exams and such. My grades were mostly C’s and even some D’s. In high school, I finally took an interest in reading after picking up J.R.R. Tolkein’s Fellowship of the Ring, and have loved reading since. Looking back, I suppose a chaotic home life, and also just lack of structure and inspiration were to blame.