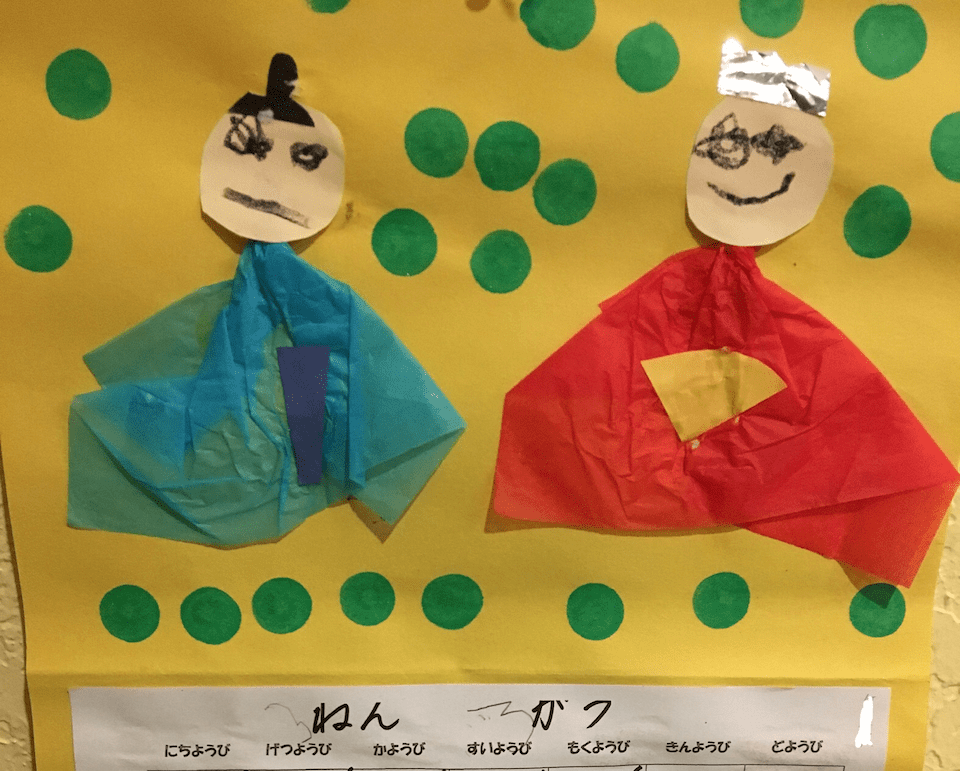

March 3rd in Japan is Girls’ Day and to celebrate I’ve decided to devote all of March to poetry from the Hyakunin Isshu from female poets.

Although most of poems in the anthology were written by men, a considerable minority (20% of the poems) are written by women as well. Many of these are found in poems 55-65 but are also scattered before and after. Many of these women represent the first female authors in world history including Lady Murasaki who wrote the Tales of Genji and her eponymous diary, and Sei Shonagon who wrote the Pillow Book. In addition was the diary of Lady Sarashina, the Gossamer Years and the writings of Lady Izumi.

Poetry in the days of the ancient Heian Court was everywhere and women wrote poetry as much as men did if not more. Like men, they participated in Imperial contests as well and made a name for themselves. Not surprisingly, some of these have been preserved in the Hyakunin Isshu, just as they were in official Imperial anthologies, such as the Kokin Wakashū. However, one interesting custom to note is that the women poets never used their own name. Instead they often used sobriquets associated with where their family was affiliated with, or their position in the Court. Lady Izumi’s father was governor of Izumi province for example.

So this month, expect some awesome poetry from the women of the Hyakunin Isshu!