The Hyakunin Isshu and its poets, the aristocracy of the Heian Period, represent a golden age of Japanese history, and a level of cultural refinement that was often imitated, but never surpassed in later generations. I have been celebrating that culture on this blog all the way back since 2011 (!), and it has always been a personal fascination of mine.

And yet, amidst all this culture and elegance there was very much a dark side to this culture too. This is encapsulated in works at the time, such as the melancholy and weariness of backbiting in the diary of Lady Murasaki, the isolation and frustration at her husband’s rampant infidelity in the Gossamer Years, among other sources. Further, the historical drama about Lady Murasaki highlights a particularly dark episode involving the succession to the Imperial Throne around the years 1000-1010.

The top positions at the Imperial Court were the Udaijin (右大臣, “Minister of the Right”) and Sadaijin (左大臣, “Minister of the Left”). The minister of the Left was higher rank than the minister of the Right. If you look at the authors of the Hyakunin Isshu, you’ll notice a few held such positions over the years: poems 14, 25, 81, and 93.

If you look at the list of poems, you’ll notice quite a few are composed by members of the elite Fujiwara clan (roughly 25-30%). In the 7th century or so, the Fujiwara had been instrumental in protecting the Imperial throne from a usurper, and handsomely rewarded for it. By the year 1000, the Fujiwara clan had grown so large and prosperous that it developed into multiple sub-clans, branches and rival groups.

I mention this because the episode I relate here relates to two powerful branches of the Fujiwara clan in their struggle for power. There’s an excellent article in Japanese about it, which I encourage you check out because it also includes scenes from the drama.

It all begins with one Fujiwara no Kaneie, husband of “Michitsuna no Haha” (poem 53) and the “villain” of the Gossamer Years. Kaneie was particularly ambitious, served under three emperors, and had three sons, who each held ministerial positions. The eldest son was Fujiawara no Michitaka whose wife was “Gidō Sanshi no Haha” (poem 54). He served as the regent for the young Emperor Ichijo, and later, Ichijo married his daughter, Teishi.

The third son of Kaneie was Fujiwara no Michinaga. Remember this name.

After Kaneie’s first son, Michitaka, died his son (Teishi’s brother) named Fujiwara no Korechika, took over that branch of the family. Korechika contended with his uncle, Michinaga, from the get-go, but Korechika made a fatal error. In a strange tale, Korechika believed that retired Emperor Kazan had been sleeping with Korechika’s own mistress. During one of Kazan’s nighttime travels, Korechika in a jealous fit shot an arrow at him and hit the retired Emperor’s sleeve. Michinaga capitalized on this incident to get his nephew Korechika banished from the capitol. This is probably something “Gidō Sanshi no Haha” would have never imagined happened to her son.

Korechika’s sister, Empress Teishi (also daughter of “Gidō Sanshi no Haha”), was now in a vulnerable position without her family to protect her. So, Michinaga pushed forward his own daughter, Shoshi, as a second wife for Emperor Ichijo. Later, the isolated and vulnerable Emperess Teishi died in childbirth. Teishi’s son, the Imperial prince Atsuyasu, appears later. The end result was that Ichijo’s remaining wife Shoshi (daughter of Michinaga) was the reigning empress now, and Michinaga used his influence to gain the title of Minister of the Left. The diary of Lady Murasaki covers this period when Shoshi gave birth to Emperor Ichijo’s second son, Atsuhira.

Let’s pause for a moment. Emperor Ichijo had married two women who were from rival factions of the Fujiwara clan: the exiled Korechika’s sister, and Minister of the Left Michinaga’s daughter, and each bore him a son.

Meanwhile, Korechika was later pardoned and made a junior minister in the Court. And yet Korechika was very bitter toward Michinaga, and his mental health took a downward spiral. He hired a Buddhist priest to help craft a series of curses against Michinaga. Eventually, this was discovered, and Korechika’s career was over and retired until his death in 1010.

Things took an unexpected turn when Ichijo retired early during the same year due to poor health, and his cousin ascended the throne as Emperor Sanjo (poem 68). Sanjo only reigned for a few years before a combination of ill-health and Michinaga’s machinations as the minister pushed him to abdicate too. This is why his poem in the Hyakunin Isshu is so melancholy: Sanjo finally ascended the throne, but ill health and Michinaga’s power-plays ended his reign soon after it began.

Emperor Sanjo’s retirement left Ichijo’s two sons as the next successor: one by Korechika’s sister (Teishi), and the other by Michinaga’s daughter (Shoshi). Which imperial prince do you think Michinaga, the Minister of the Left, wanted to ascend the throne? Michinaga obviously wanted his grandson to be next emperor, so Michinaga could assume the position of regent (Sessho).

Due to age, Atsuyasu, son of the first empress Teishi, should have been Emperor (Atsuhira was too young), but he was bypassed entirely and faded out of history. The child Atsuhira, grandson of Michinaga, ascended the throne as Emperor Go-Ichijo (“The latter Ichijo”).

Korechika’s own son, Michimasa (poem 63), was totally shut out of the Imperial Court as well, and mostly lived a reckless life, trolling Michinaga’s administration, and being just plain obnoxious. His life took a downward spiral much like his father had done, and that branch of the Fujiwara’s male line died out. Michimasa’s fate is particularly dark and tragic.

This multi-generational struggle between two branches of the Fujiwara clan to control the Imperial throne through marriage resulted in Michinaga being the most powerful man in Japan at the time. It also adversely affected many lives of poets in the Hyakunin Isshu. We saw the examples of Michimasa, son of Korechika, and Emperor Sanjo above.

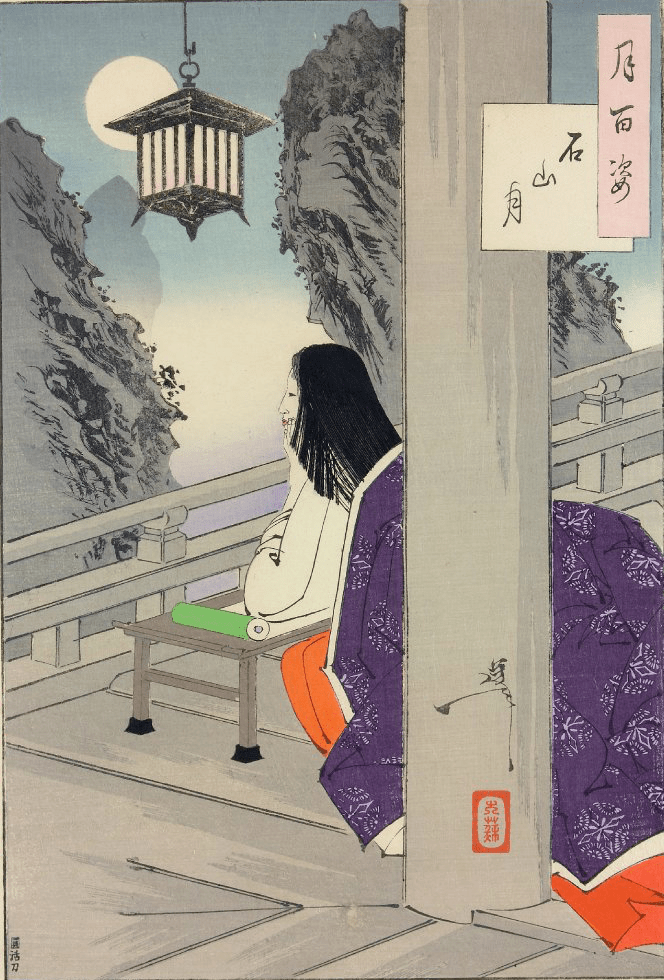

In the case of Sei Shonagon (poem 62), who served Empress Teishi and was loyal to the losing faction, she faded away in retirement. Her Pillow Book is a last swan-song of the time spent serving Empress Teishi, and conveys a very rosy look. It’s not hard to see it was also a subtle middle-finger to Michinaga’s faction.

Many of the ladies in waiting to Michinaga’s daughter, Shoshi, were also poets of the Hyakunin Isshu:

- Lady Izumi (poem 56),

- Lady Murasaki (poem 57), author of the Tales of Genji

- Akazome Emon (poem 59), her sister had an affair with Michinaga’s older brother Michitaka much to the chagrin of “Gidō Sanshi no Haha” (poem 54)

- Ko-Shikibu no Naishi (poem 60), Lady Izumi’s daughter

- Lady Ise (poem 61)

By association with Empress Shoshi, not Empress Teishi, they all benefitted and their daughters and family members rose to positions in the Court over time. Lady Murasaki’s daughter, Daini no Sanmi (poem 58), eventually became a wet nurse for future Emperor Reizei and attained the third rank in the Court which was quite high.

Additionally, men like Fujiwara no Kintō (poem 55) benefitted from the association with Michinaga as well.

In the end, there were obvious winners and losers in this struggle. It was not all poetry parties, moon-viewing, and romantic dalliances; people’s lives profited or were destroyed due to hair-splitting power struggles that took generations to complete.

As alluded in Lady Murasaki’s diary, the whole thing was golden sham.