Hi all,

This somewhat different than my usual posts, but I after posting by poem by the Mother of Michitsuna (poem 53), I decided to read her diary, titled the Gossamer Years, or kagerō nikki (蜻蛉日記) in Japanese.

The “Mother of Michitsuna” is never named as per the culture of the Heian Period of Japan. She lived a generation or two before other famous female authors such as Sei Shonagon (poem 62), Lady Murasaki (poem 57), Lady Izumi (poem 56), etc. The translator, Professor Seidensticker, did a masterful job translating this difficult text. In reading the footnotes, you can see he struggled a lot with the vagaries of the text, and with the language, where it’s not always clear from the context who’s talking about whom.

At the time, she was from a lesser branch of the powerful Fujiwara Family, but she married Fujiwara no Kane’ie, who was gradually moving up the ranks of the Heian Court. Fujiwara clan, Kane’ie had to contend with various other members of the court, and even his own clan, to gain the prestigious position of Regent, which he finally accomplished in 986 as regent for Emperor Ichijō. His sons, Michinaga and Michitaka both became regents and the most powerful men in the Heian Court. Lady Murasaki (poem 57) served under Michinaga, by the way, and they are the subject of a Japanese historical drama in 2024.

Suffice to say, Kane’ie was a very ambitious and influential man. As such, he married a few women, as per Heian Period custom, and also carried on various affairs, having yet more children on top of this. One of these children is the author of poem 52.

The Mother of Michitsuna began her diary when Kane’ie first met her, and courted her. Her own father was the governor of a remote province, a mediocre position in the Court, but he gave his blessing and they were married. In the early part of the Diary, she writes about all the passionate love poems they exchanged and such. It seemed like a good relationship early on, but the Mother of Michitsuna wasn’t Kane’ie’s first wife. She was probably his second or third wife (the diary isn’t clear on this), and his time was divided between his wives. When he was not around, she stayed in one of the outer rooms of his mansion and just passed the time with her hand-maidens.

But as the diary shows, Kane’ie’s visits came less and less often. In time she tracked him down to an alleyway where he’d spend the night with some girl, presumably a bastard child of one of the emperors, and rumor has it that she had a son by him as well. The author was not surprisingly furious and jealous, but completely powerless to stop him. She writes about the sound of his carriage driving by the residence, but not even stopping by to say hello, while she spent night after night alone.

Later, in Book 3, she finds about more of his affairs and children, and adopts the daughter of another of his lovers so that she doesn’t have to spend her young life in a monastery. Strangely, Kane’ie’s brother takes an interest in the child (his own niece) and gets very pushy about marrying her which again was not unusual at the time among the nobility. The Mother of Michitsuna expends a lot of effort to delay and make excuses for the girl, and pleads with her husband to help her, with only modest success.

This agonizing loneliness and sense of abandonment is the primary theme of the Gossamer Years. There are times when Kane’ie and the Mother of Michitsuna grow closer briefly, such as when Kane’ie falls gravely ill or when the Mother of Michitsuna loses her own mother to old age, but after a while he forgets her again. Their relationship is quite strained in the diary though, because she is frequently enraged by his insensitivity, but Kane’ie gets frustrated by her “moods” and can’t seem to understand why she is mad at him. Worse, he blames her regularly as to why he doesn’t come anymore.

At one point, the Mother of Michitsuna, now old and a has-been, has had it with Kane’ie and abruptly moves out of the mansion and retreats to a monastery which causes quite a stir at the Court and humiliates Kane’ie. Furious he tries to send messenger after messenger to bring her back, but she refuses for a long time. Finally, after a combination of threats and pleading, she agrees to return home, but they soon fall into the old routine again.

The Mother of Michitsuna only had one child with Kane’ie, Michitsuna of course (who rose to be a minister of the Court, though not as powerful as his half-brothers), and Kane’ie seems to take much pride in his son, but also periodically uses him as a weapon for getting back at his mother.

Thus, the Gossamer Years is a long, and often very depressing diary of a noblewoman in a very unsatisfying marriage who spent many dreary days alone. The diary ends abruptly one day when there’s a knock at her residence, and it appears that she never took up the brush again. Nobody knows why. As for the diary itself, it is full of poems exchanged back and forth. Most of these are mediocre poems, though as you can see, Fujiwara no Teika did include one of them in his famous Hyakunin Isshu anthology. However, these other poems are also waka poems, just like the ones you read here on this blog, and it’s amazing how many poems people exchanged in those days just to express things like “how are you?” or “can you come over?”.

In today’s modern age where text-messages replace letters or poems, we can send messages much quicker now, but it’s amazing how much skill and subtlety it took to get a simple point across to someone back then. Not surprisingly, the kinds of feelings of frustration a broken-hearted woman might have were probably much worse then because they were traditionally very isolated in their homes. It was uncommon for women, especially powerful noblewomen, to go out on their own without permission from their husbands, and their lifestyle and huge robes made it difficult to travel far anyway. Customs and such would also get in the way too. In short, women spent most of their time indoors in their home with nothing to do.

As for the Mother of Michitsuna herself, it’s tempting to make her a tragic, almost saintly figure, but in reality she was prone to faults of her own. When the “woman in the alley” had the misfortune of losing her home to a fire, the author felt a moment of triumph and petty revenge without any remorse. In another, more troubling scene late in book one, she encounters a defeated rival (it’s not clear who) and gloats over her:

At the Hollyhock Festival in the Fourth Month I recognized the carriage of a lady who had once been my rival, and I deliberately had my own carriage stopped beside it. While we were waiting, rather bored, for the procession to go by, I sent over the first line of a poem, attached to an orange and a hollyhock: “The hollyhock should promise a meeting, but the orange tells us we have yet to wait.” After a time she sent back a line to complete the couplet: “Today for the first time I know the perverseness of her who sends this bitter yellow fruit.” “Why just today—she must have had similar feelings for years,” said one of my women. When I told the Prince [Kane’ie] of the incident, he remarked, to our considerable amusement, that the closing line the lady really had in mind was probably more like this: “This fruit you send me, I would like to grind it to bits with my teeth.”

pg. 59, trans. Seidensticker.

Clearly the Mother of Michitsuna was not above petty rivalries or revenge when it suited her.

Anyhow, what makes the Gossamer Years such a significant work of literature is that it was the first and only real diary of the Heian Period to really express how a woman felt in that small, cloistered world. The Heian Period had many great works of literature, both by men and women, but these works were either fiction (e.g. Tales of Genji), poetry (e.g. Tales of Ise) or just dry, stodgy journals about oval events. The Gossamer Years is much more “raw” and unfiltered than other works at the time. The Mother of Michitsuna is not a strong or witty writer like Sei Shonagon or Lady Murasaki, but you can really feel her pain at times, and wonder why she puts up with him. Then again, the customs of the time gave her few options.

But as you see later in Book 3, it was the culture of the time, not unlike the cloistered French Aristocracy centuries later. The marriage laws from the Taika Reform were vague and full of loopholes, so men could marry as often as they could afford, and affairs were pretty rampant as other poetry in the Hyakunin Isshu regularly show. So while I do enjoy the Hyakunin Isshu and the culture of the Heian Period very much, the Gossamer Years was a sobering reminder that there was a serious side to it as well.

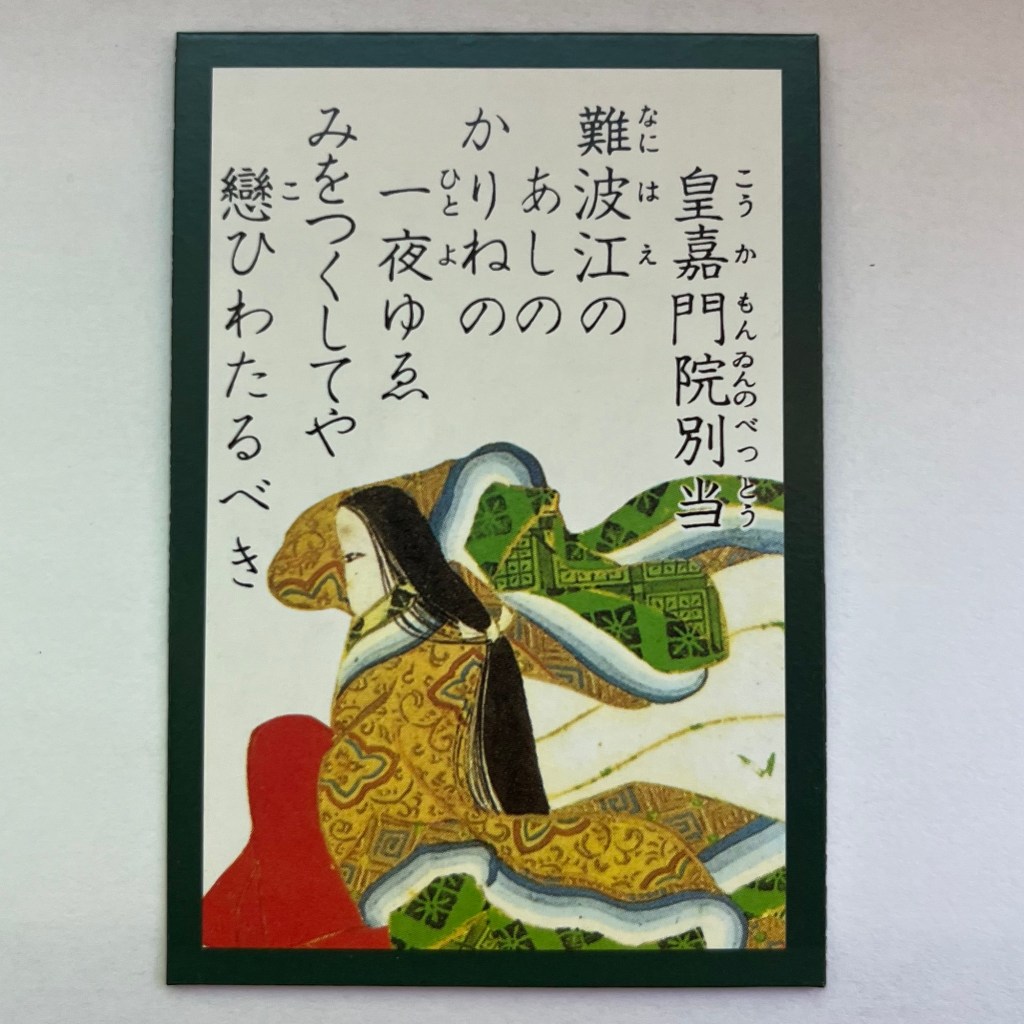

P.S. Featured photo is a scene from the Genji Monogatari (“The Tales of Genji)”, Chapter “YADORI GI”( mistletoe ), by Lady Murasaki (poem 57). Imperial court in Kyoto, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons