This is another poem in our series leading up to Valentine’s Day. This one is perhaps a bit more unrequited, than the last poem I posted here:

| Japanese | Romanization | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| あはれとも | Awaré to mo | Not one person who would |

| いふべき人は | Iu beki hito wa | call my plight pathetic |

| 思ほえで | Omoedé | comes at all to mind, |

| 身のいたづらに | Mi no itazura ni | and so, uselessly, |

| なりぬべきかな | Narinu beki kana | I must surely die! |

This poem was composed by Kentokukō (謙徳公, 924-972) also known as “Lord Kentoku”, or simply Fujiwara no Koremasa. Koremasa served as regent to the Emperor from 970 onward, and was frequently involved in compiling (and writing poems for) the second Imperial anthology of the time, the Gosenshō.

The poem, simply put, is Koremasa’s efforts to gain a girl’s attention, even after she spurned him previously. Mostow explains that according to the original sources, this poem was composed by Koremasa thinking “I will not be defeated!” and sent this poem as a last-ditch effort.

Nowadays, we might call such people stalkers, but at the time, this kind of persistent, dramatic effort wasn’t unusual. Men of the Court might try months if not years to gain a girl’s attention, and if she spurned him a few times, he might have chosen to persist, or possibly find a new lover.

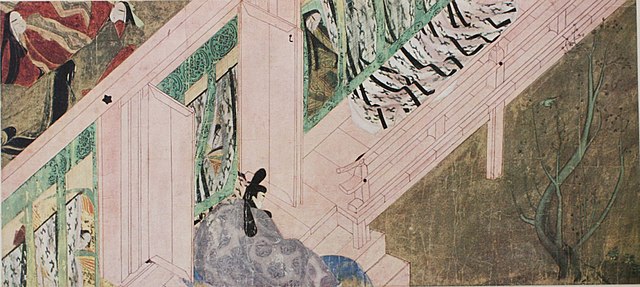

P.S. Featured photo is a scene of the Chapter “TAKEKAWA “(Bamboo River) of Illustrated handscroll of Tale of Genji (written by MURASAKI SHIKIBU(11th cent.)., Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons