Hi everyone,

This poem has quite a story behind it and relates a little to the poem posted previously:

| Japanese | Romanization | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| わびぬれば | Wabi nureba | Miserable, |

| 今はた同じ | Ima hata onaji | now, it is all the same, |

| 難波なる | Naniwa naru | Channel-markers at Naniwa— |

| みをつくしても | Mi wo tsukushitemo | even if it costs my life, |

| あはむとぞ思ふ | Awan to zo omou | I will see you again! |

The poem’s author, Motoyoshi Shinnō (元良親王, 890 – 943), the Crown Prince Motoyoshi, was the eldest son of the mad Emperor Yozei (poem 13), who was forced to abdicate prematurely. This likely affected Motoyoshi’s chances of assuming the throne, and before long Emperor Koko (poem 15) was enthroned instead. As an Imperial prince with nothing to do, Motoyoshi turned all his energy to women. My new book points out that the poetry collection that Motoyoshi left behind is almost entirely about women and sex.

According to commentaries, this poem was real and not part of a themed poetry contest. Motoyoshi, apparently, was in love with one of the hand-maidens of the retired Emperor Uda. The maiden, daughter of the powerful Fujiwara no Tokihira, had already given birth to 3 sons for Emperor Uda and was highly favored by him, but Motoyoshi persisted in his love, even if it cost him his reputation. Bear in mind that this was the same Fujiwara no Tokihira who was instrumental in getting Uda’s favorite advisor, Sugawara no Michizane (poem 24), exiled.

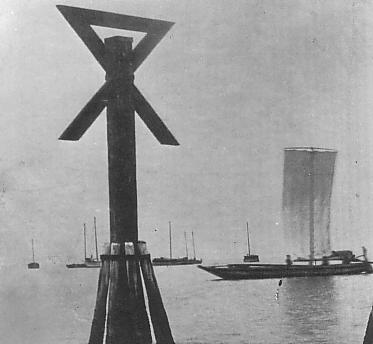

The main “pivot word” here is the phrase mi wo tsukushitemo, where miotsukushi (澪標) are famous water-markers in Japanese culture as pictured above, photograph taken during the Meiji era (Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons). But the poem can also be read as 身を尽くしても meaning “even if it exhausts my life”. So, rather than the subtle romantic allusions your normally see in poetry from this era, Motoyoshi is going all-out and making a big gamble.