As I wrote previously, I have been spending a lot of time trying find more effective training methods for myself and for new, foreign Karuta players because of the scarcity of resources. One website that has been particularly helpful in Japanese is Karuta Club, managed by the Meijin (master player) Kawase Masayoshi and his wife.

It’s a pretty nice site and has a ton of training and resources, though almost all of it is in Japanese. There is a nice English-language introduction that is worth reading.

But for this post I wanted to focus on one particularly helpful article. This teaches a method of memorization called nakama-waké.

The method seems a bit complicated upfront but really helps in those 15 minutes (or 30 seconds on the app) when you have to memorize the board, and uses knowledge you probably already know: the kimari-ji.

Let’s look at my kimari-ji chart here. You can see how the cards are group by first syllable : “ha” cards, “tsu” cards, “ki” cards, “wa” cards and so on.

Kawase’s article suggests that after you learn the kimari-ji, next invest time memorizing how many are in each group. If you look at the chart, there are only two cards in the “tsu” (つ) group, compared to seven in the “wa” (わ) group, or 16 in the “a” (あ) group. Some groups are very large, some are very small.

Let’s use the examples of the “ha” group. From the chart we can see that there are four cards that start with “ha” (は):

| Kami no Ku (upper verses) | Shimo nu Ku (lower verses) | Poem No. |

|---|---|---|

| はなさそう あらしのにわの ゆきならで | ふりゆくものはわかみなりけり | 96 |

| はなのいろは うつりにけりな いたずらに | わかみよにふるなかめせしまに | 9 |

| はるすぎて なつきにけらし しろたえの | ころもほすてふあまのかくやま | 2 |

| はるのよの ゆめばかりなる たまくらに | かひなくたたむなこそをしけれ | 67 |

If we remember that the “ha” group has 4 cards total, and when you are memorizing at the start of the match, you can determine which of the four are on the board. The rest can be safely ignored as kara-fuda (“empty cards”).

This separation of similar cards (“friends”) between the ones on the board and the ones that aren’t is why this is called nakama-waké (仲間わけ): “separating friends”.

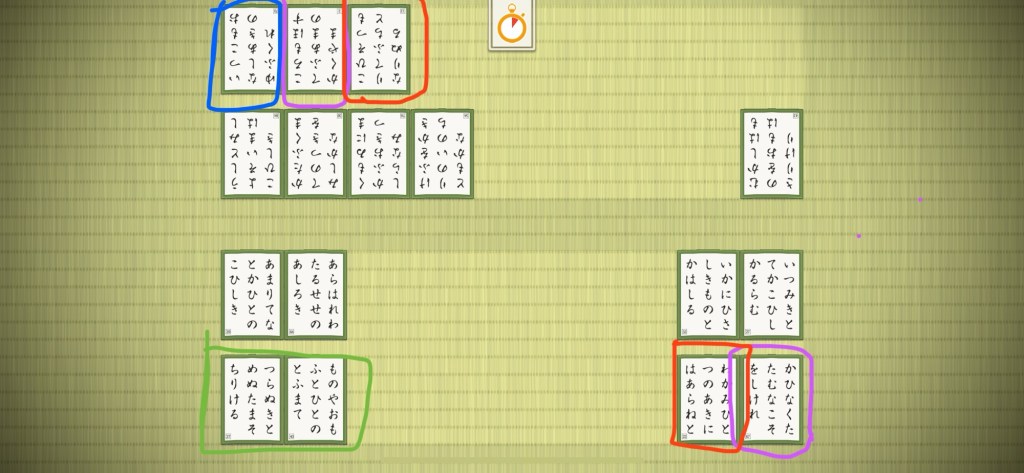

Using the online karuta app, let’s demonstrate this. Here’s a game I played earlier, using default settings: 8 cards per side, only 30 seconds to memorize. The cards are all laid out, and my opponent (the computer) and I are memorizing.

Of the four “ha” cards, I can see two on the board, highlighted in purple. The two cards are “haruno” (はるの) on my side and “harusu” (はるす) on the opponent’s side. That means the other two in the group “hanano” (はなそ) and “hanasa” (はなさ) can be totally ignored if they are read aloud. That helps me avoid accidentally taking the wrong “ha” card and getting a penalty.

While we’re here, you might notice that both “shi” (し) cards are on the board, highlighted in green: “shira” (しら) and “shino” (しの). Even better they are on my side. That means I can just put group them together and simply listen for “shi” (し). Of course, the danger is that the opponent knows this too. Position matters.

Similarly, both cards of the “tsu” (つ) group are on the board too, highlighted in red. They are on opposite sides of the board though, so I still have to be careful to distinguish which is which when read. But it also means there are no “empty” tsu cards either.

Finally, of the seven unique “one syllable” cards, only one of them is on the board: “sa” (さ) which I’ve highlighted in blue. That means I can totally ignore the other six: “mu” (む), “su” (す), “me” (め), “fu” (ふ), “ho” (ほ) and “se” (せ) if they are read.

This may seem like more work upfront, and it does take time to get used to thinking like this, but it really helps in a couple ways:

- Your memorization process is more structured, less haphazard, and so you can memorize a full board of 50 cards more easily.

- Less risk of penalties because you’re only paying attention to the cards you know are on the board per group, and disregarding the rest.

If you’re relatively new to karuta and you find this process intimidating, you can focus on smaller, easier groups of cards for now: the one, two, and three card groups. With experience, and familiarity, you can then expand to larger, more difficult groups and even use this trick with the huge “a” group.