My journey with the game of Karuta began one August day in 2023 with the kind folks at a local karuta club, and right away I loved the game. However, over time, I realized that the competitive style of karuta, like you see in the anime Chihayafuru, was not for me. The constant pressure to grind out game after game to make incremental improvements, especially as a working parent with little time or energy for such endeavors, made me feel increasingly hopeless about making any real gains.1 Finally, with my children getting older, and one of them graduating, I had to take a long break from karuta. It just wasn’t fun anymore.

Recently, I’ve been playing again with a small informal group where we just mess around a bit, and play shorter Karuta games using the casual format. This is how most Japanese people play in Japan, by the way.

Thus, I wanted to share my experiences lately with readers in hopes that they may find ways to keep enjoying karuta, or help introduce it to people outside of Japan who didn’t learn it in grade school.

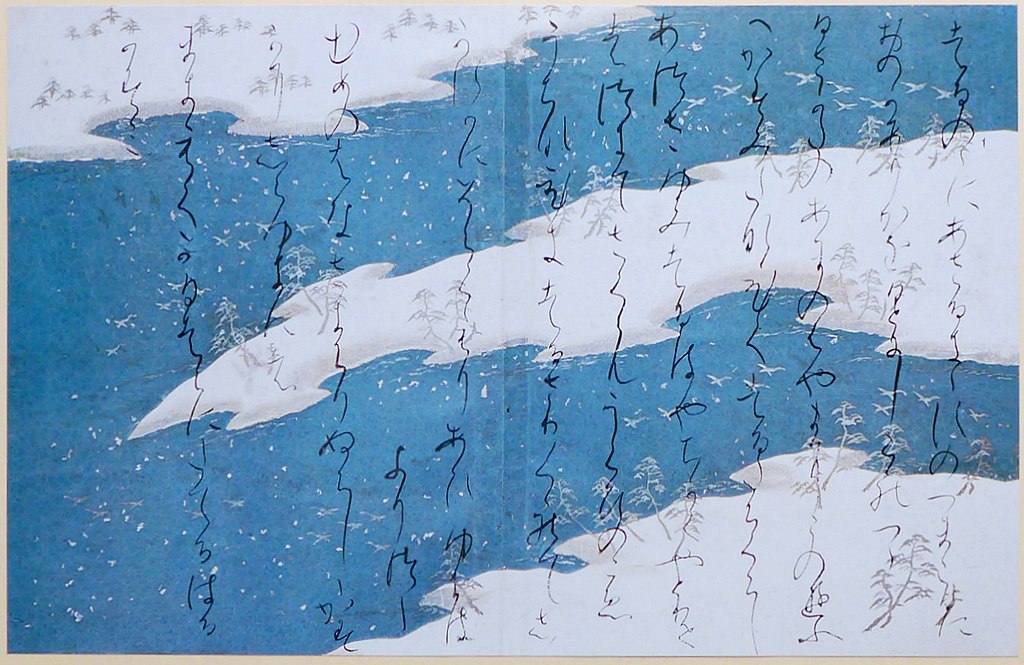

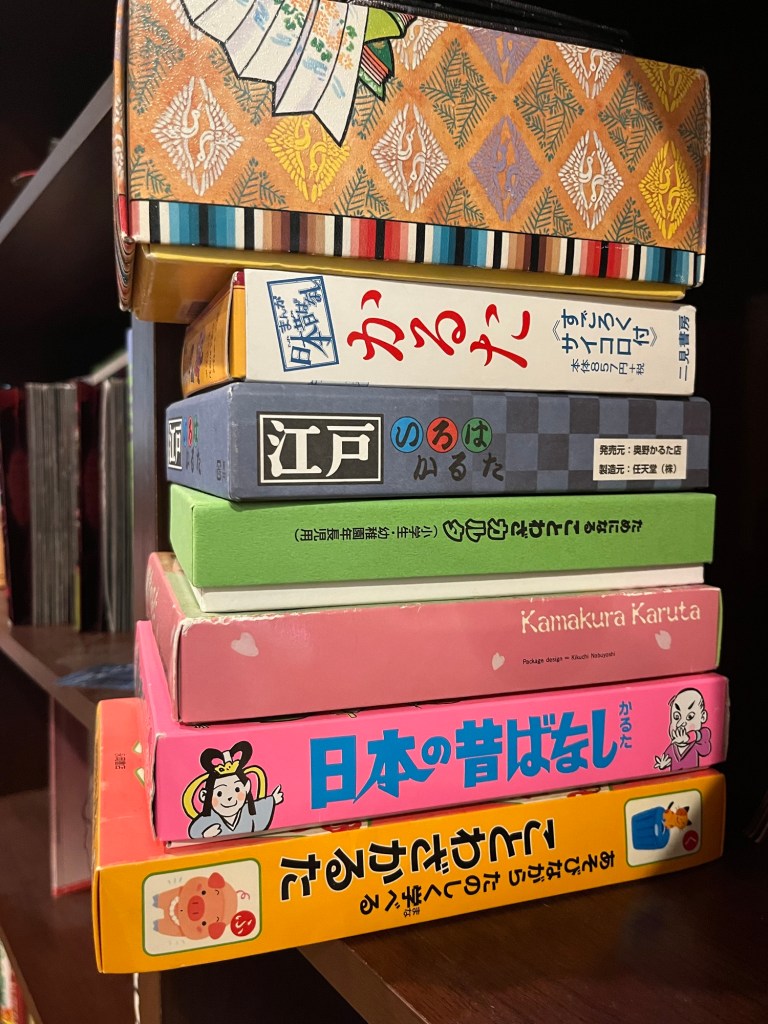

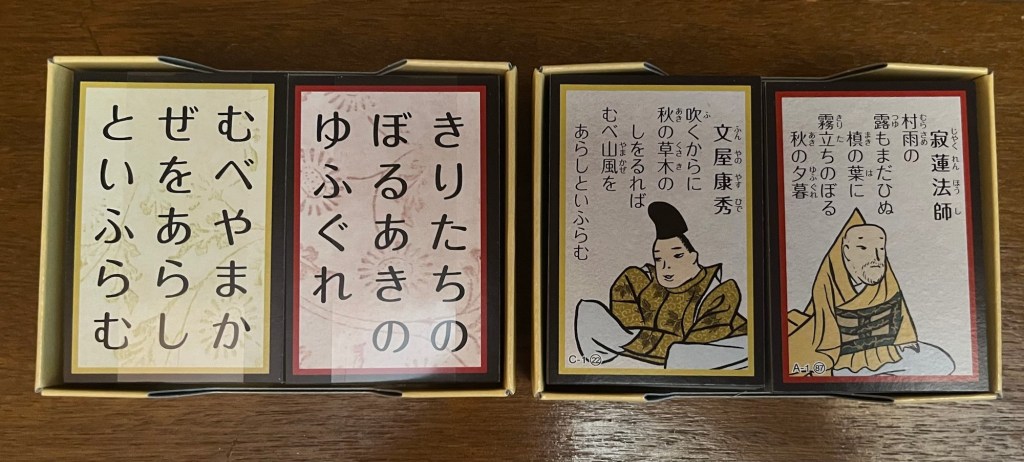

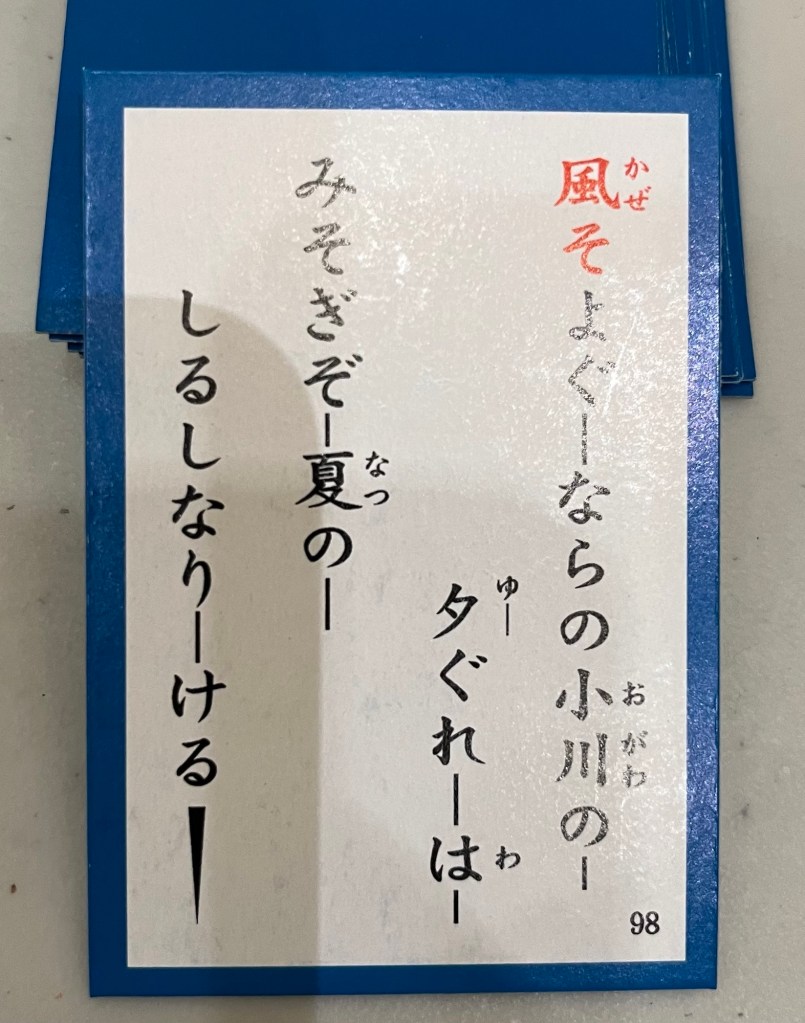

For starters, I ordered this 5-color Hyakunin Isshu set online from the good people at Oishi Tengudo last year,2 and after using the set a few times, I finally realized this five-color set is different than the more well-known version sold in Japan. It uses different colors, and divides the cards differently. My karuta reader apps were not set to recite poems according to Oishi Tengudo groupings, so I was really confused at first.

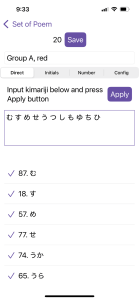

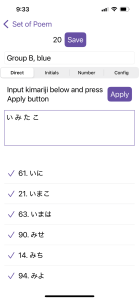

Using my favorite karuta reader app, Wasuramoti (Android and iOS), I decided to make custom lists based on the Oishi Tengudo groupings. You can do this too in Wasuramoti by selecting Advanced Config, then Set of Poem:

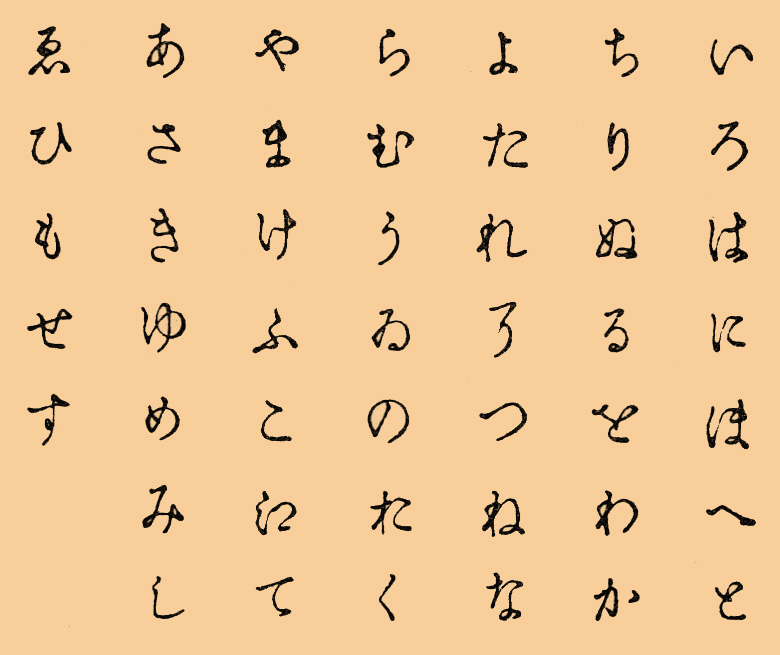

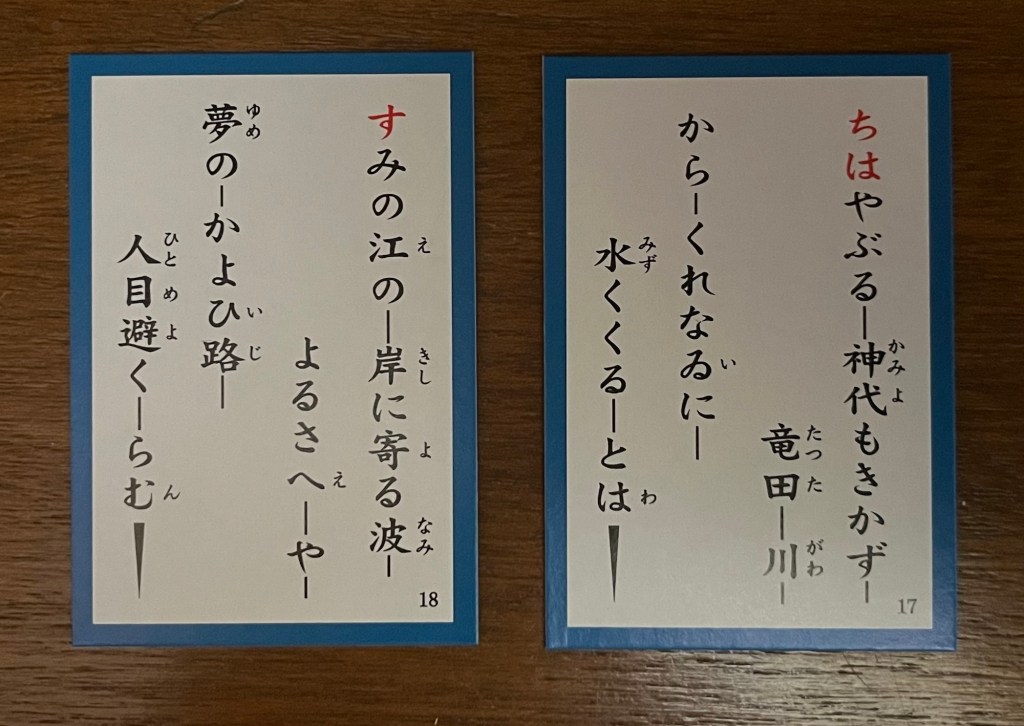

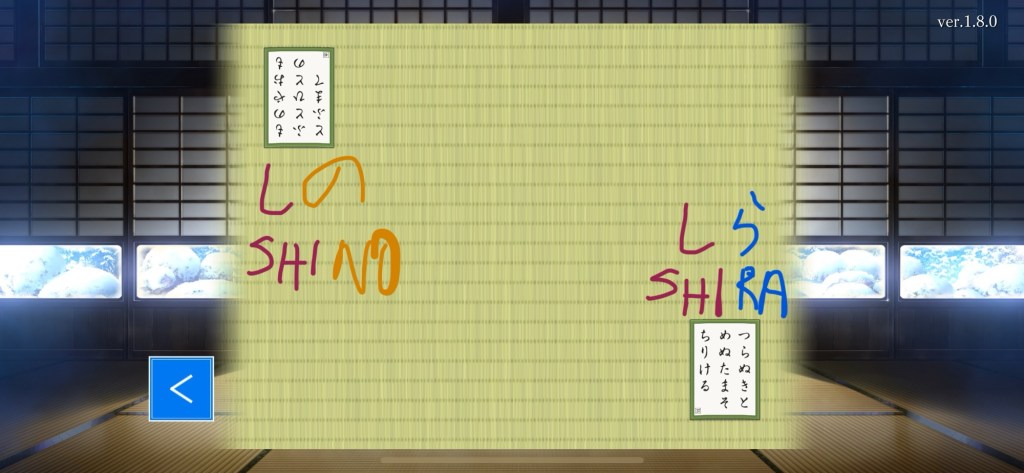

In the Oishi Tengudo set, the “red” group (also called Group A), is comprised of poems whose kimari-ji (starting syllables) start with む (mu), す (su), め (me), せ (se), う (u), つ (tsu), し (shi), も (mo), ゆ (yu), ち (chi), and ひ (hi). These cards have very few or no tomofuda (cards with similar kimari-ji), so they’re distinct and easy to learn first. I created my custom list with 20 cards, just like my physical set.

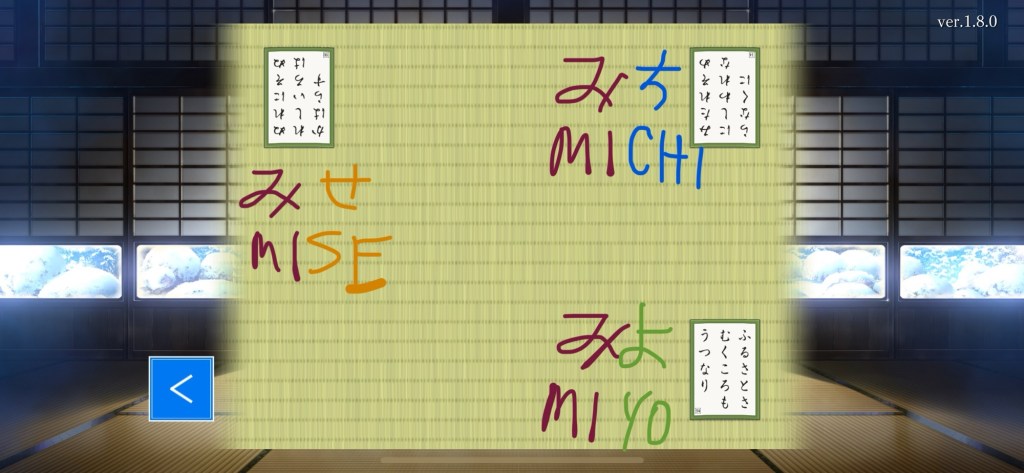

I made a similar custom list for Group B (“blue”) as well. This group is a bit harder because it includes cards whose kimari-ji have slightly more tomofuda cards (3-4): い (i), み (mi), た (ta), and こ (ko). So, there’s a bit more effort required to distinguish one card from another. Yet it’s still the second easiest group.

… and so on.

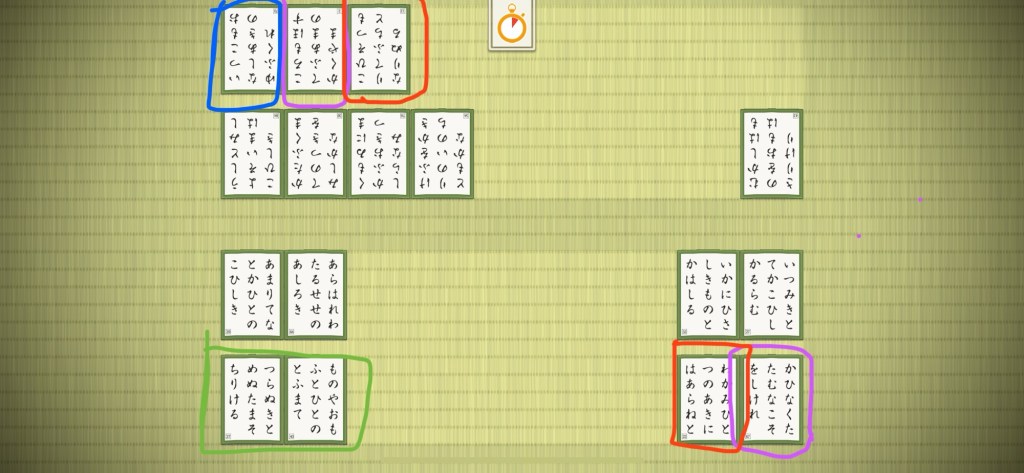

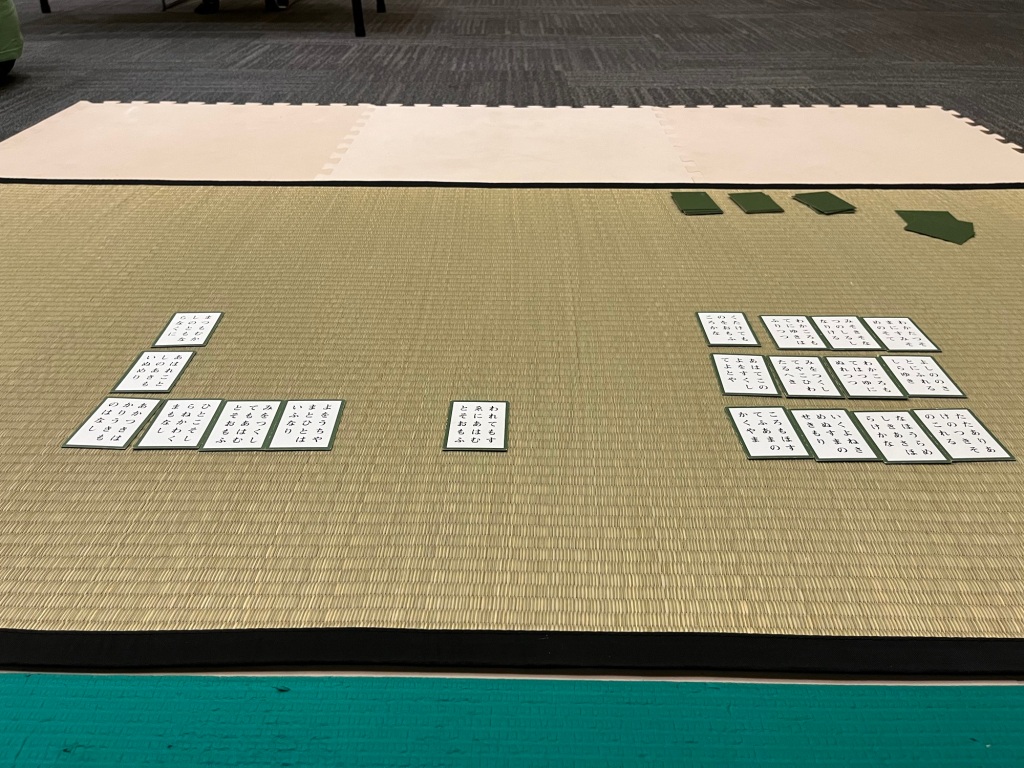

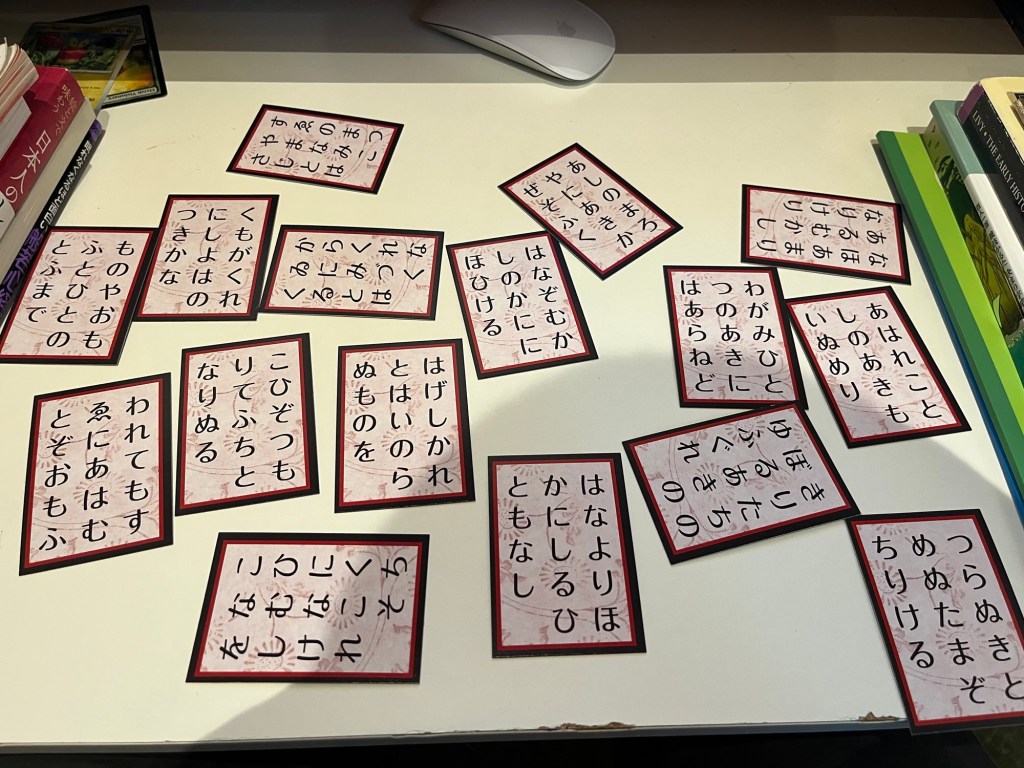

When I practice, I just grab the color I want to play (“red”, or Group A in this case) and scatter then on my desk, casual-style.

Then in the Wasuramoti app, I select the group of poems I want (see above), set the app to display the torifuda, same as cards on my desk, and set the reader to “auto” mode so it doesn’t stop with each poem. I just want to see if I can recognize the poem before too late. I don’t care very much about speed.

It is fun to play this way. I can finish a game pretty quickly (roughly ten minutes) and it is not very exhausting. Since I chose the easiest set of cards first, I remembered many of them pretty quickly despite the long hiatus, which was gratifying.

This format of playing smaller sets of cards, with optional levels of difficulty, and no threat of penalties, seems to be a great way to introduce to new players as well. I was happy to see that a new player, who had experience with Japanese language, quickly pick up the game, took a few cards of her own, and had a great time. If people aren’t having a great time, why play karuta?

Karuta is super fun, and a great game to enjoy throughout one’s life. However, if you are struggling, don’t blame yourself. Instead, find what you enjoy about karuta, pick a more gentle format, and focus on that, not what the A-rank players are doing.

Happy gaming!

1 The final nail in the coffin was when I joined some online communities which I soon realized were very focused on competition, and very little on actually enjoying the culture of the Hyakunin Isshu. It was just another sport, with physical training regimens, and techniques to edge out your opponent. That is not why I created this blog back in 2011, and not why I continue to enjoy the Hyakunin Isshu now. I had left the world of competitive card games behind when I quit playing Magic the Gathering before the Pandemic, and didn’t want to resume.

2 They only ship in Japan as far as I can tell, and with tariffs making things more expensive, it might be hard to get outside of Japan. Thus, I am adding a new index page for five-color Hyakunin Isshu to help readers make their own sets