Since I began, this blog has focused on a period of Japanese history which I like to call “Classical Japan”, or “Japanese Antiquity”.1 That’s just a convenient name I call it.

But most researchers and historians tend to divide Japan’s history into “periods” (jidai, 時代) based on where the capitol was at the time. So, precisely speaking, this blog and the Hyakunin Isshu cover a 500-period of history overlapping the Asuka (6th – 8th c.), Nara (8th c.) and Heian Periods (8th – 12th c.), while dipping our toes just a bit into the the early Kamakura Period (12th – 14th c.) for certain poems (poems 93, 99 and 100 for example). For the sake of the Manyoshu we also ventured even further back to somewhat murkier periods of time since some of the very early poets of the Hyakunin Isshu (poems 1, 2, 3 and 4 for example) were also contributors.

But the blog has never really explored anything beyond the early 13th century because that’s when things effectively end. The Hyakunin Isshu was compiled, the aristocracy of the Heian Period were totally sidelined by the new samurai class, and Japan continued on in a new trajectory. The aristocracy still lived until the modern era, and Imperial poetry anthologies were issued from time to time, but the quality and popularity gradually petered out. As poem 100 above alludes to, this era embodied by the Hyakunin Isshu was effectively over.

For the purposes of this blog, why pay attention to anything that comes after?

Well, I attended Professor Mostow’s recent lecture at the University of Washington, and I learned that history of the Hyakunin Isshu kept going. In fact, it was all the rage in the much later Edo Period (17th – 19th c.).

Japan by the Edo Period was pretty different than the earlier Heian Period. By this point, Japan had been effectively ruled by one military government or another for centuries, while the capitol had shifted from Kyoto in central Japan, to a fortified castle town in eastern Japan called Edo (江戸). Edo started as a fishing town, but soon grew into a metropolis thanks to good urban planning and government policies that forced rival warlords to stay there every other year. Edo, later the modern capitol of Tokyo, was one of the largest cities in the world at one point.

After a century of constant warfare throughout Japan, the Edo Period brought unprecedented stability and cultural flourishing. Its isolation from European explorers and rival Asian powers meant that people turned inward and rediscovered Japanese culture that had been forgotten in ages past due to war and instability.

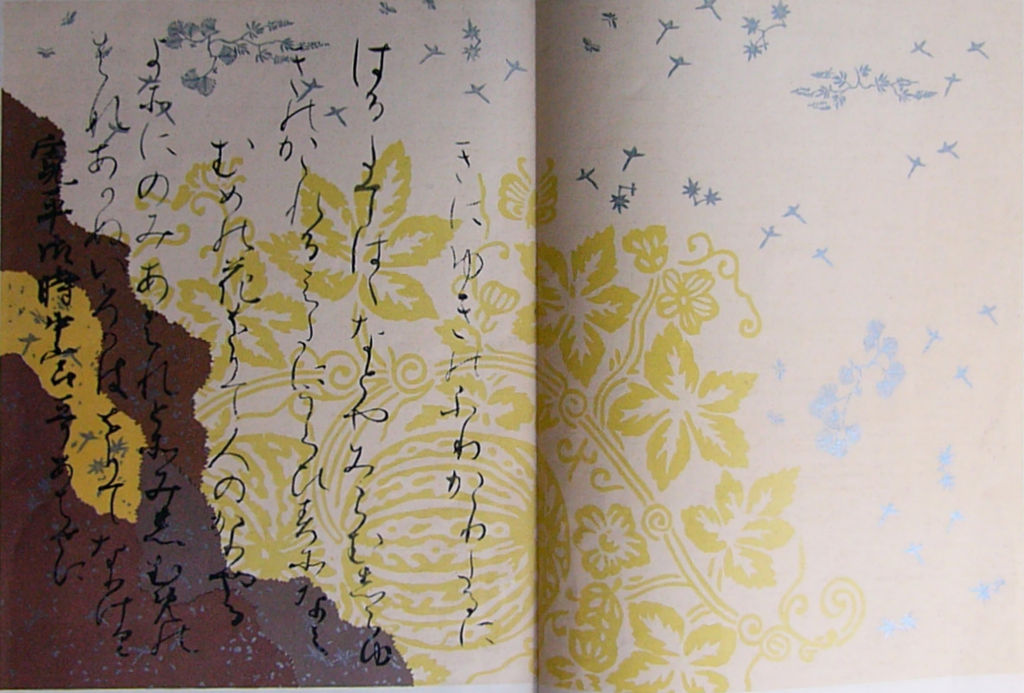

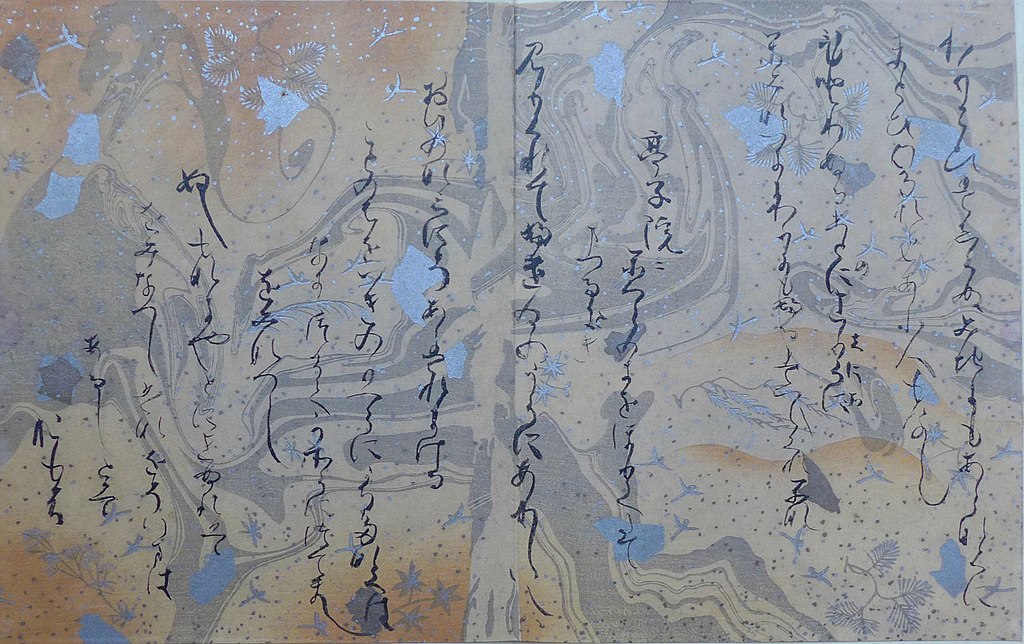

One aspect of this flourishing was the invention of block printing which suddenly allowed the masses to enjoy reading in a way that earlier generations had not. Books became far more affordable, and more available, and suddenly a variety of books about the Hyakunin Isshu were published. There were books about the Hyakunin Isshu as far back as the 15th century, namely the Ōei-shō (応永抄) composed in 1406, but mass-printing made books much more accessible and allowed for a greater variety.

Professor Mostow has collected and aggregated many examples on his website here. Take a look if you can, there are some neat scans of really old documents from the era.

One common usage of the Hyakunin Isshu at the time, according to Professor Mostow, was in the instruction of girls. Books about young women’s education were a popular subject, and such books would work lessons in along with poems of the Hyakunin Isshu. For example, Professor Mostow posted scans from a book called the Hyakunin Isshu Jokun Shō (“A Selection of the Hyakunin Isshu for Women’s Instruction” ?), published in 1849. Another example can be found here.

Men were often taught things like Confucian values and such. And yet, even the boys learned about the Hyakunin Isshu from their mothers who had been raised on it. Also, books that were published for men about the Hyakunin Isshu often did so under the theme of Kokugaku (“national learning”).

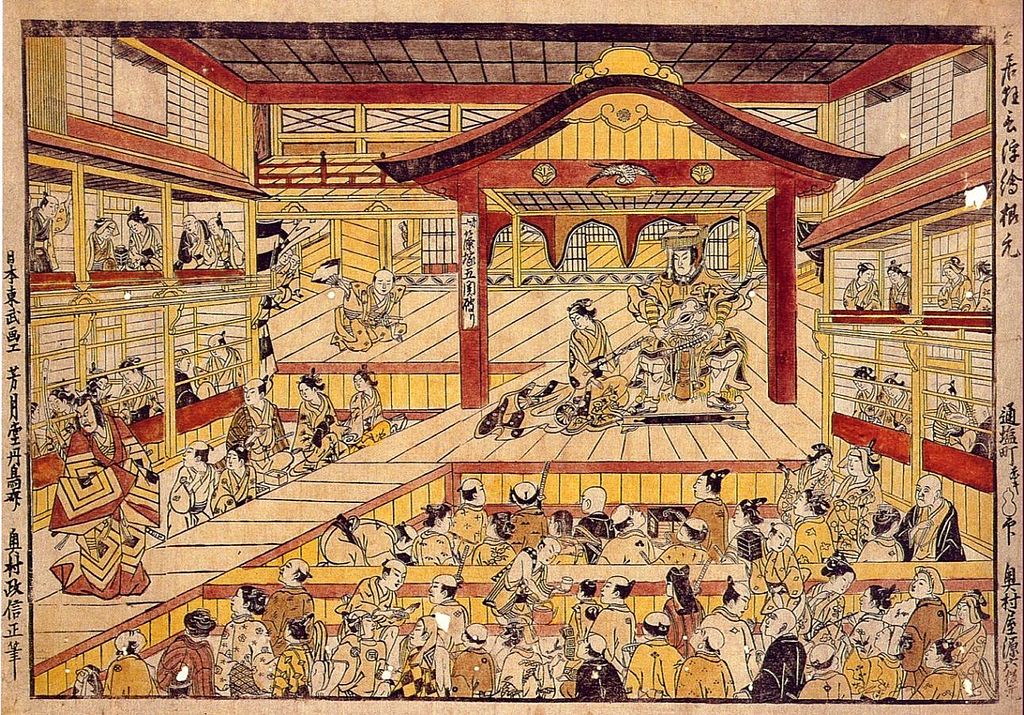

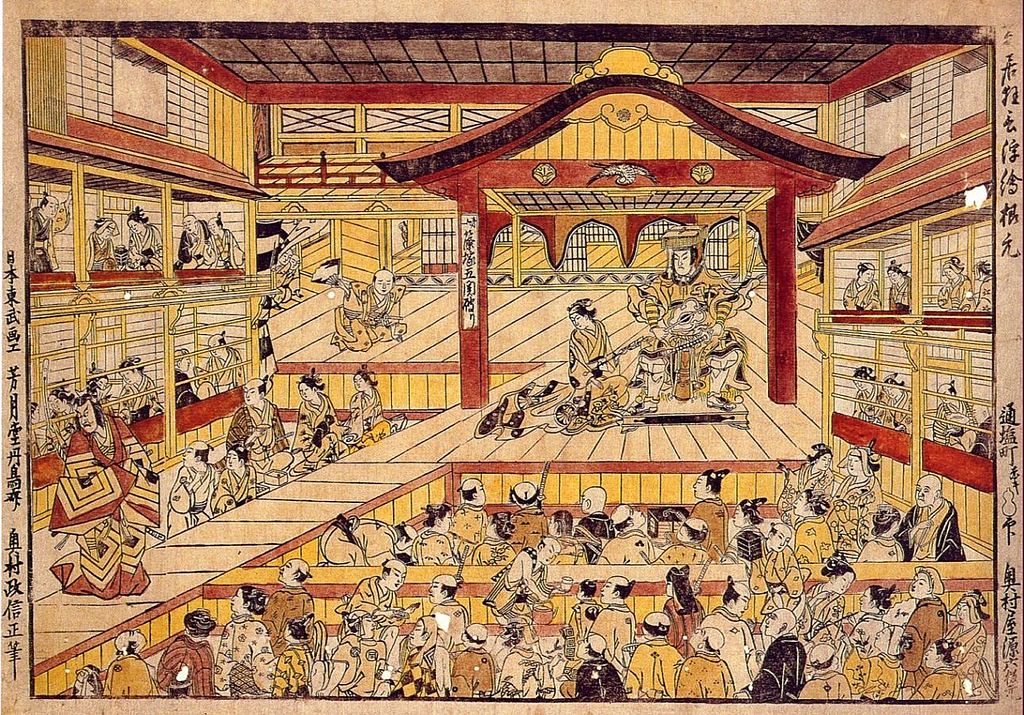

The high point of Edo Period culture, and something that influences Tokyo even today was the Genroku Period (1688 – 1704). Many things people imagine of pre-modern Tokyo, such as Kabuki theater and Ukiyo-e prints, have their origin in this brief period. The Hyakunin Isshu was used in some Ukiyo-e block prints too. Since many of these images were racy or scandalous, publishers would work in poetry of the Hyakunin Isshu to either obfuscate the content from Edo government censors, or to lend a more “classy” air to the image. I found some examples here.

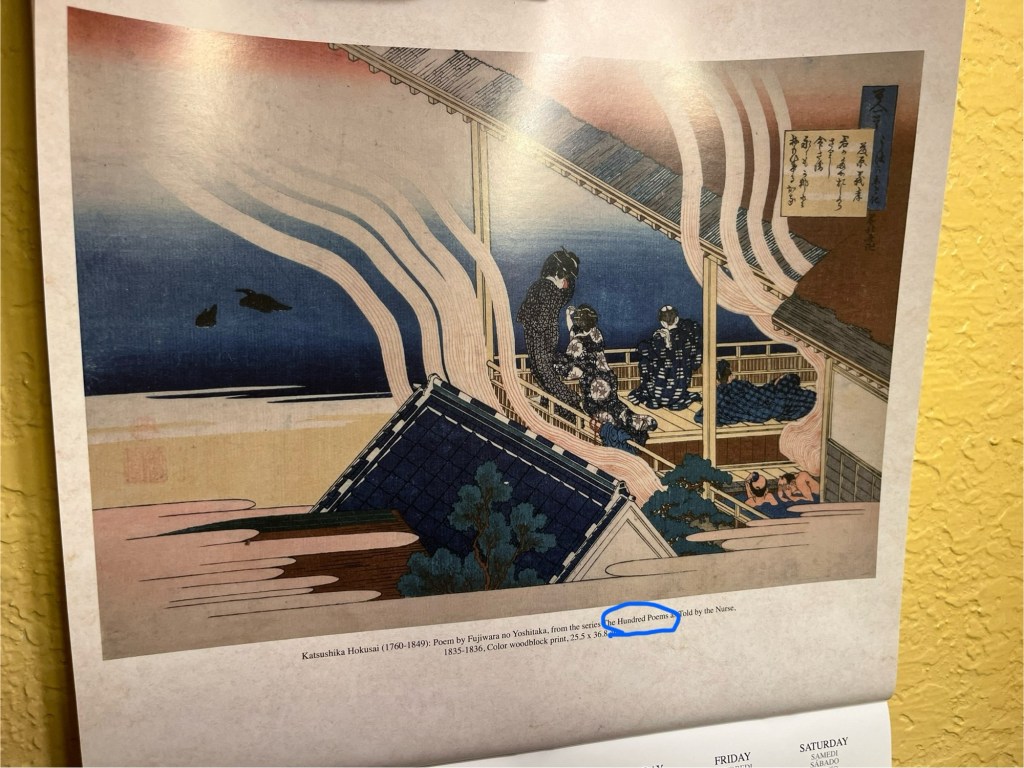

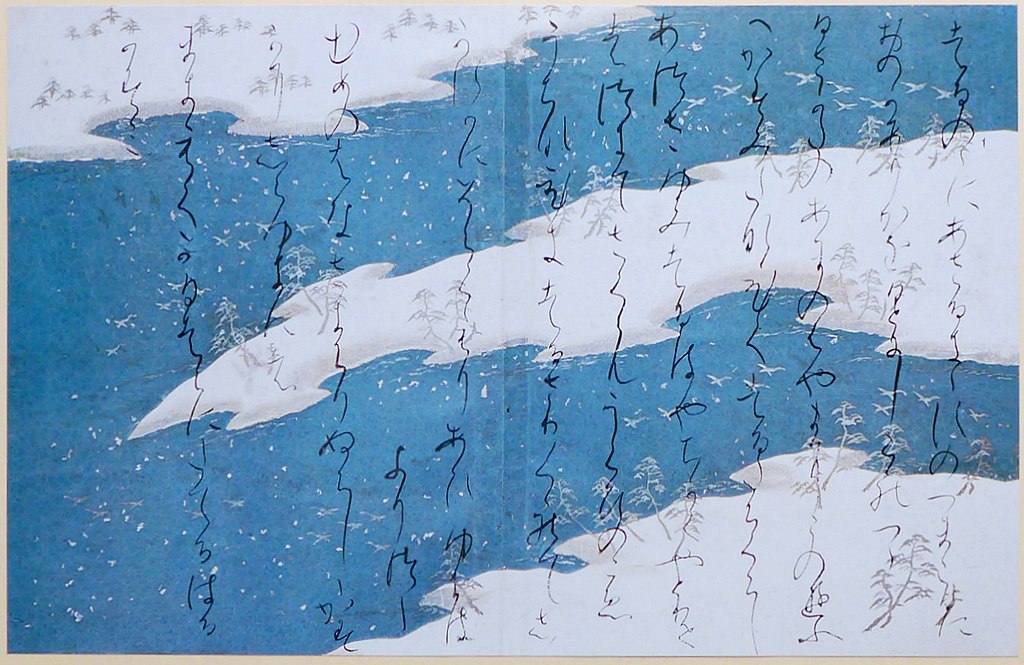

Even the famous artist Hokusai of “Great Wave” fame made block prints that would feature poems of the Hyakunin Isshu. We have a calendar at home and I was surprised to see this Hokusai block print with poem 50 (きみがためお) composed in cursive:

It turns out this is part of a series by Hokusai called the Uba ga Etoki (姥がゑとき), or more formally the 百人一首姥がゑとき2 , which means something like the “The Illustrated Hyakunin Isshu As Told By a Nurse(maid?)”. You can see more examples of this work here.

Anyhow, it’s fascinating that as literacy among the populace improved during the Edo Period, and access to information via books and printing increased, popular interpretations and illustrations of the Hyakunin Isshu took on a new life. The Hyakunin Isshu was, by that point, already 600 years old, and yet it enjoyed a revival that we benefit from today in the form of anime, karuta, and so on.3

Special thanks to Professor Mostow for his lecture and website! Also, check out Professor Mostow’s new book!4

1 I suppose my reason for doing this is that the end of the Heian Period and the subsequent change in Japan was somewhat similar to the fall of the Western Roman Empire in Europe, and how later generations of feudal lords kept up some of the trappings of the Romans, and yet it was still a different society altogether. But in the end, this is just one history nerd’s interpretation.

2 In modern Japanese 百人一首うばが絵解. See this post for more explanation.

3 Although social media and Internet reveal a pretty ugly side to humanity, it does also lead a similar explosion in cultural and accessibility. Two sides of the same coin, I suppose.

4 This is my associates link on Amazon. I get a small amount of credit for any purchases made through here. Feel free to purchase directly from University of Hawaii press instead though.