For our final poem for Valentine’s Day, I thought this was another good choice:

| Japanese | Romanization | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| 明けぬれば | Akenureba | Because it has dawned, |

| 暮るるものとは | Kururu mono to wa | it will become night again— |

| 知りながら | Shiri nagara | this I know, and yet, |

| なほうらめしき | Nao urameshiki | ah, how hateful it is— |

| あさぼらけかな | Asaborake kana | the first cold light of morning! |

The author of the poem, Fujiwara no Michinobu Ason (藤原道信朝臣, 972-994), was the adopted son of the powerful Fujiwara no Kane’ie, husband of the mother of Michitsuna (poem 53) and subject of the Gossamer Years. His birth mother was the daughter of Fujiwara no Koretada (poem 45). Michinobu for his part, benefitted from his adoptive father’s influence, and rose to the Court rank of 4th-upper, and a position as part of the Imperial Guard (sakon no chūjō, 左近中将).

However, Michinobu seemed more interested in Waka poetry than in politics. He was close with Fujiwara no Sanekata (poem 51) and Fujiwara no Kinto (poem 55), and would often gather with them for poetry sessions. Further, Michinobu had a secret relationship with one of the court ladies under Emperor Kazan, named Enshi Jo-ō (婉子女王), but eventually he lost her to a political marriage with the powerful Fujiwara no Sanesuke. Sadly, Michinobu later died from due smallpox, which took his life at the age of 23.

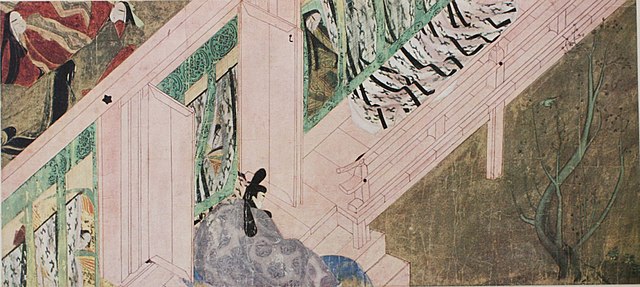

This is another classic “Morning After” poem, which we’ve featured here, here and here.

Lord Michinobu dreads the rising sun because it means he has to sneak back to his own residence, away from his lover. Judging by his reaction, it must have been a night well-spent together. 😏

Happy Valentine’s Day!