This clever little poem shows the battle of the sexes as it existed 1,000 years ago:

| Japanese | Romanization | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| 春の夜の | Haru no yo no | With your arm as my pillow |

| 夢ばかりなる | Yume bakari naru | for no more than a brief |

| たまくらに | Tamakura ni | spring night’s dream, |

| かひなく立たむ | Kainaku tatan | how I would regret my name |

| 名こそをしけれ | Na koso oshikere | coming, pointlessly, to ‘arm! |

The author, known as Suō no Naishi (周防内侍, dates unknown), the “Suō Handmaid”, was so named because her father was governor Suō Province. As mentioned before, this was a common method used by female authors (cf. poem 65), so unfortunately, their real names are rarely known. This is another poem that speaks to the importance of a woman’s reputation in the ancient Court of Japan, just like poem 65. However, this one is much more playful and shows a lot of wit.

According to the back-story, there was a social gathering at the Nijō-In (二条院), the woman’s quarters at the palace. The woman there were relaxing, and the author of this poem said, “I wish I had a pillow”. At that moment, one Fujiwara no Tada’ie happen to walk by, and hearing this stuck his arm through the bamboo screen (御簾, misu) and said, “Here, takes this as your pillow!”.

In reply, the author composed this poem. As Professor Mostow points out, the word for arm here (kaina) is a pun for pointless (kainaku).

People flirted pretty clever back in those days. 😏

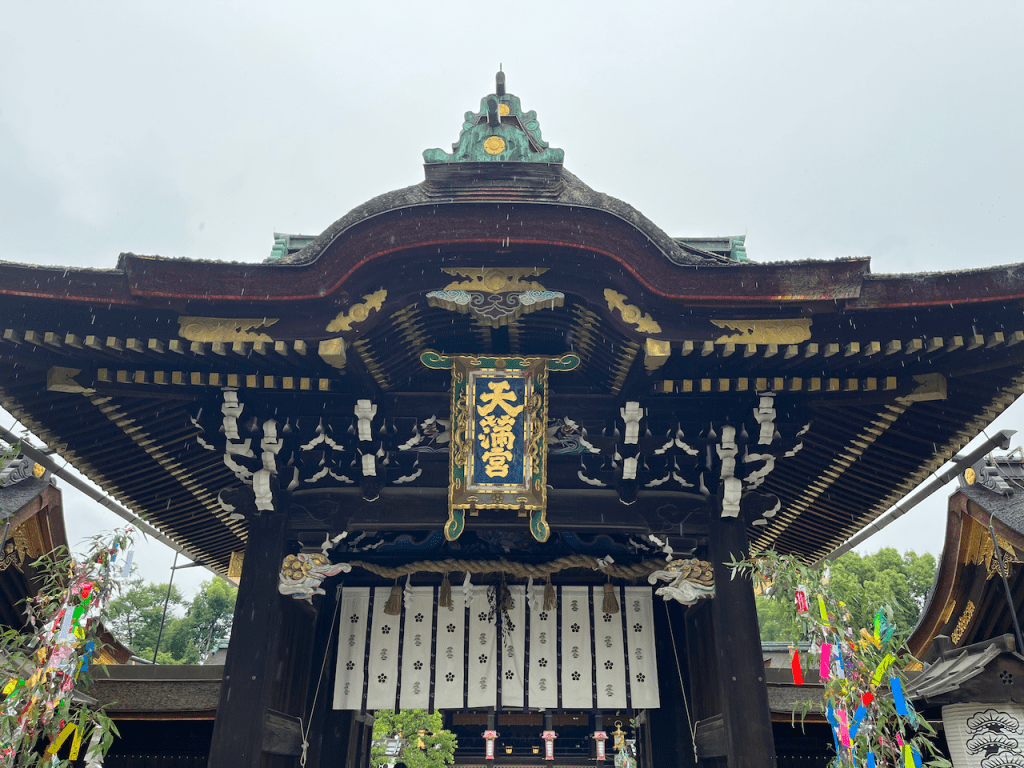

P.S. Featured photo by Christian Kadluba, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons