In the past year, I’ve spent a fair amount of time talking about what’s called competitive karuta (kyōgi karuta, 競技カルタ in Japanese) after my first encounters, and subsequent efforts to learn to play the game. The truth is is in that in recent months, for various reasons, I’ve really started to wind down my involvement in the competitive karuta scene. I do enjoy playing karuta games, but frankly just not a very competitive person at heart, and the thought of investing what little time I have to increasingly small, incremental gains in an obscure sport doesn’t really appeal to me. I learned how to play the game, and consider myself decent at it, but the poetic side of the Hyakunin Isshu is still what appeals to me most.

Further, I realized through talking with Japanese people that a lot of people play casual karuta games, not competitive. This mundane side of karuta gaming is not featured in animé such as Chihayafuru. However it is a common past-time for people who enjoy karuta and the Hyakunin Isshu poems,1 but don’t necessarily want to invest countless hours in practice, drills, and so on. So, I wanted to explore the casual side of karuta gaming, and help casual players find ways to enjoy the game without the intense stress of competition.2

Japanese “Karuta”, especially karuta games based on the Hyakunin Isshu, come in many forms. There is a spectrum of very easy games on one end, and competitive karuta on the other. If you think of it like a video game with difficult settings, then games like bozu-mekuri are easy mode. You don’t have to know anything about the cards, it is visual only, and the rules are simple. On the other hand, competitive karuta is hard mode: you are playing against some very good players, the margin of error is very small (in higher ranks), and every bit counts including hand-techniques, card position, mental training, and so on. It’s a tough struggle, with lots of exciting moments, but sometimes also crushing defeats.

So between “easy mode” of bozu-mekuri, and “hard mode” of competitive karuta, isn’t there anything in between? Turns out, yes.

I found good examples of casual karuta games through my Hyakunin Isshu Daijiten book, mentioned here, as well as subsequent information online. Let’s look at the games of chirashi-tori and genpei gassen.

Chirashi-Tori

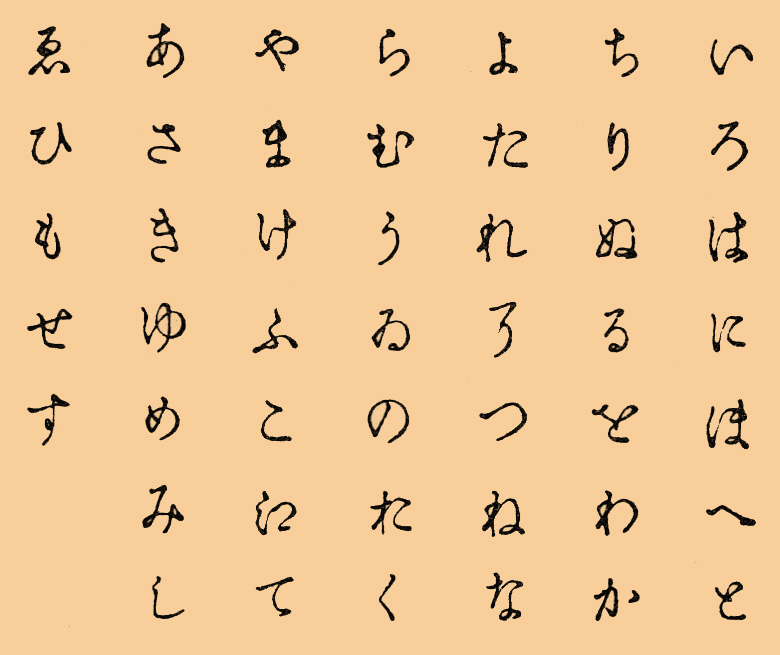

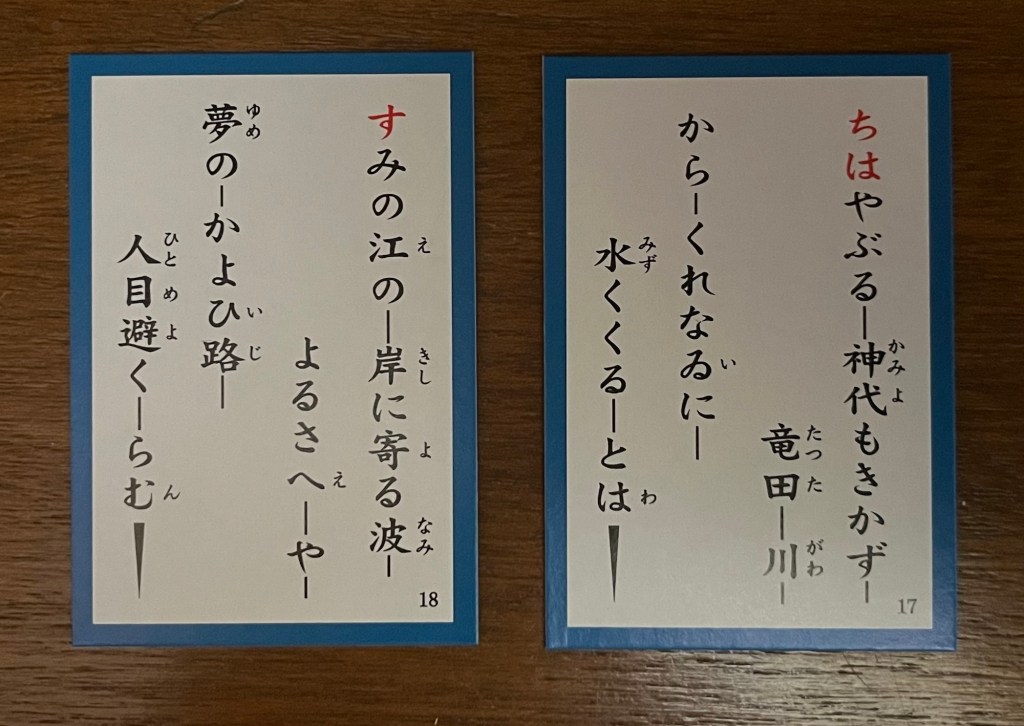

The game of chirashi-tori (散らし取り), meaning “scatter and take”, can be thought of as a lightweight version of competitive karuta. You don’t have to know the kimariji, but it helps, nor do you have to think about card position. In the same way, penalties don’t exist. You do need to know how to read the hiragana script though, even if slowly.

The game basically works like so:

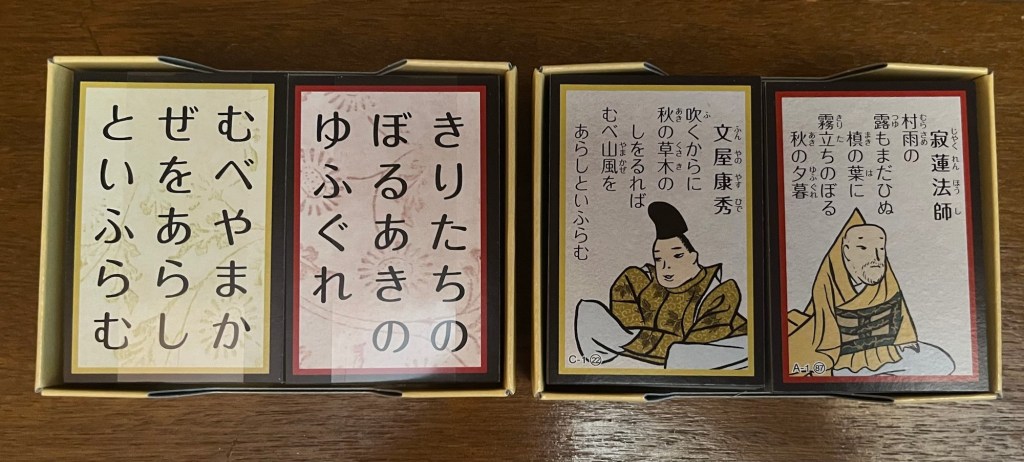

- Take all 100 torifuda cards (the ones that are not illustrated) and spread them around face up. Players sit around the pile, spread out evenly.

- Similar to competitive karuta, someone else (not a player) reads a random yomifuda card (the illustrated ones). It’s customary to read the last two verses twice.

- You can also use one of several nice karuta reader apps on your mobile phone too.

- As the poem is being read, whoever finds it’ll the corresponding card touches it, or takes it. If they are correct, they remove the card from the field and keep it in a stack next to them, face down.

- The reader then draws another card and a new round begins until there are no more cards on the field.

- Whoever took the most cards by the end of the game wins. 🏆

In terms of difficulty, this is the next step up from bozu-mekuri in that you do have to be able to read hiragana, but it’s a nice first step to getting familiar with the poems with little or no training. Even though knowing the kimariji is not required, knowing some can help you recognize some cards on the field quicker.

Genpei Gassen

The name of this game comes from the climatic war in 12th-century Japanese history: the Genpei War, pitting the Genji (“Gen”) clan versus the Heike (“pei”) clan. Unlike Chirashi-tori where each person plays separately, in Genpei Gassen people divide into even teams. Ostensibly one side plays the Heike clan, and the other the Genji clan.

There are a few other differences to Chirashi-tori:

- The two teams sit facing one another, with teammates sitting side by side. Ideally, 5 or 7 people will play. The odd-man-out is the reader (see below).

- The 100 torifuda cards (non-illustrated ones) are evenly divided into two groups of 50. Half the cards go to one side (i.e. facing them), and the other 50 go to the other team. Arrange the cards into three rows, roughly equal.

- To play the game, a separate person reads a random yomifuda card (the illustrated ones), one at a time. It’s customary to read the last two verses twice.

- You can also use one of several nice karuta reader apps on your mobile phone too.

- As the poem is being read, players from both sides try to find the corresponding card somewhere on the field. If someone finds the poem, they may touch it, or take it. If they are correct, they remove the card from the field and keep it in a stack, face down.

- The first team to get to zero cards on their side wins. 🏆

- Similar to competitive karuta, if you take a card from the opponent’s side, you send over a card from your side. This way, their number stays the same, but since you correctly took a card, your side reduces by one.

This games has the advantage of being a gentler version of competitive karuta, but still keeping the look and feel of it. As with Chirashi-tori, you will need to be able to read hiragana script, and knowing the kimariji, even some of them, gives you an advantage, but these are things you’d learn anyway from repeated play. Also, having a team develops some fun and interesting strategies.

Five Color Hyakunin Isshu

Finally, if you still want the look and feel of competitive Karuta, but an easier version, you can look at Five Color Hyakunin Isshu. This way you can play a much smaller set of cards and warm up to the full competitive version. The catch is that it requires a custom set, or you will have to make your own by customizing a standard set.

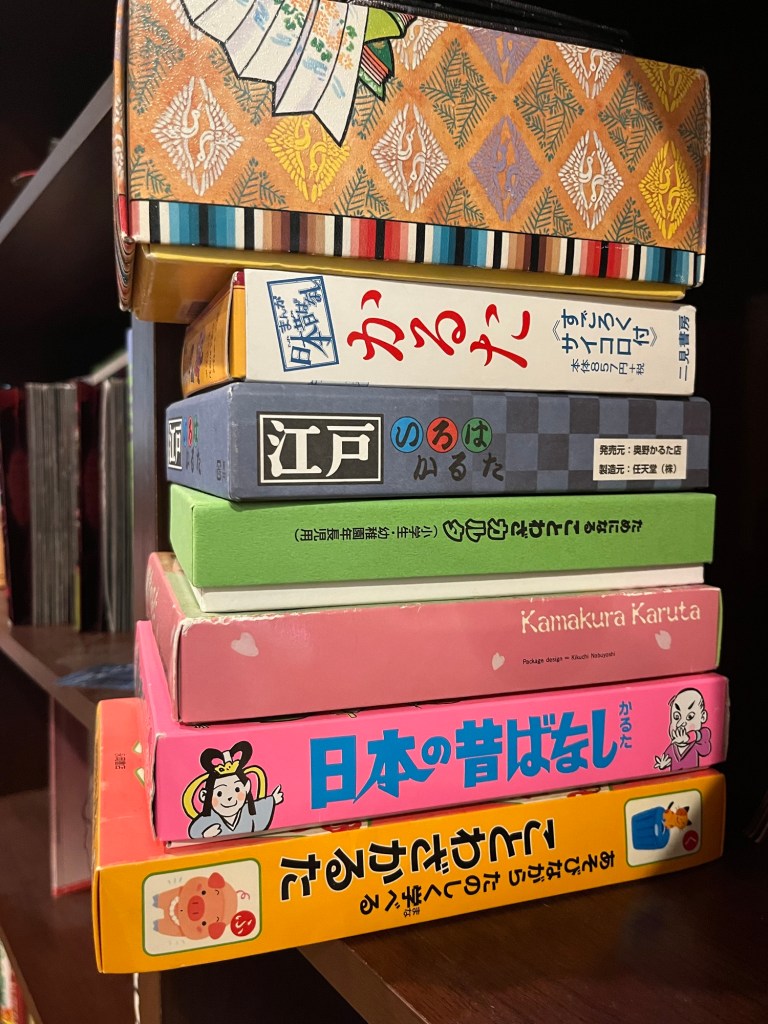

Non-Hyakunin Isshu Karuta

If, like me, you somehow get a hold of a karuta set not featuring the Hyakunin Isshu poems (there are a surprising number in Japan), the games above will still work. Many karuta sets, regardless of theme, use the same basic format: two sets of cards for reading and taking. They are all meant to be read by someone, with other players finding the correct, corresponding card.

Conclusion

The game of Karuta at heart is just that : a game. It’s a great way to savor the poetry of the Hyakunin Isshu in a fun interactive way, and the more I explore it the more I realize that there are games to suit every player. If you purchase a set, you can try any number of games with friends or even by yourself. The most important thing is HAVE FUN! If poem 96 teaches us anything, it’s that life is short.

P.S. Speaking from experience, playing

1 Fun story, in summer of 2024, I was in Japan again briefly to visit my wife’s family, and found the famous Okuno Karuta store in Tokyo. I didn’t post about it as there wasn’t much to say (I didn’t find what I was looking for, tbh). I did see a tour group of elderly Japanese people come into the store in a single mass, and many of them bought karuta goods in one form or another before leaving again. So, it’s definitely a pasttime, but not quite the way I expected when I first learned about the game.

2 I don’t mean this lightly either. Some people definitely revel in competition, but I find such situations always make me intensely nervous, and uncomfortable, even when I win. Used to feel this way about Magic the Gathering competitions too. I thought maybe it was just me until I spoke to someone Japanese who also felt that way when playing competitive karuta. They just wanted to play casual games. That’s when I started to realize that there were different games for different crowds, but all of them celebrate the Hyakunin Isshu poetry in some way.

Similarly, some people want to play Pokemon TCG or Magic the Gathering at home with friends, rather than big competitions. Other people live for the thrill of competition. There’s enough room in the game for both types of players. I personally prefer Hyakunin Isshu karuta myself.